Chilling past of Indonesia’s new President Prabowo Subianto exposed

More than a million Aussies flock to this paradise on our doorstep each year. Now, it’s being run by a former “war criminal” with a disturbing past.

Leaders

Don't miss out on the headlines from Leaders. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation, has a new president – the colourful former military general Prabowo Subianto, who was sworn in late last month.

The 73-year-old swept to victory at the polls in February this year, after previously running for – and losing – the presidency in 2014 and 2019 to his predecessor Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi.

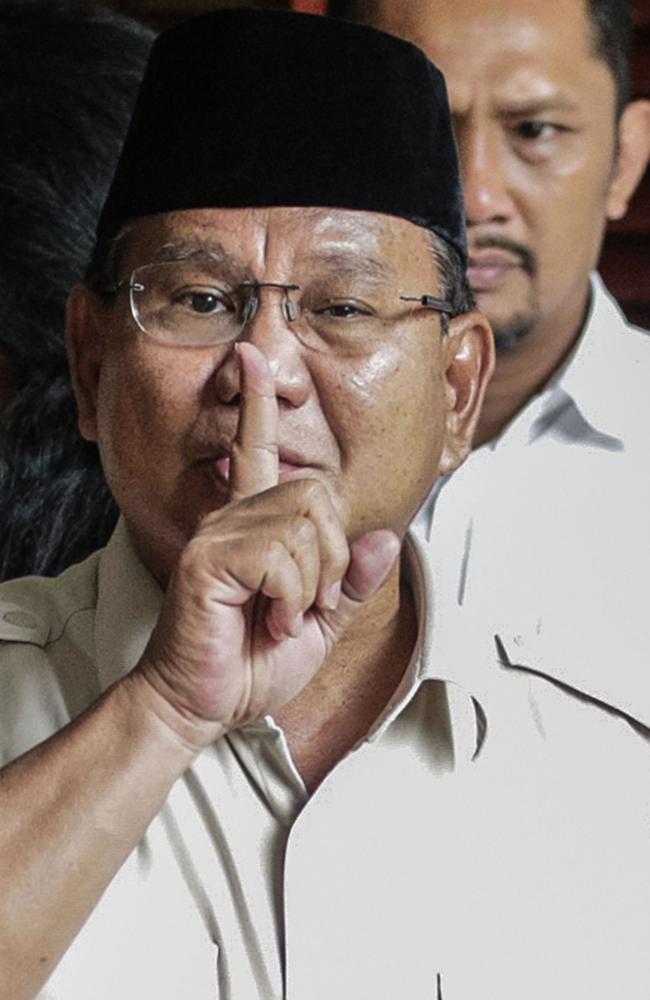

As a former military strongman, Prabowo has long been a polarising figure, having been accused of myriad war crimes in Timor Leste and Indonesia’s West Papua, as well as human rights abuses in 1998 during the fall of former president Suharto.

These allegations, for which Prabowo has never been tried in court, saw him quietly banned from travelling to the United States and Australia for over two decades.

“It was known that he had been banned from entering Australia, although he never decided to test it and make an incident out of it,” Ian Wilson, a lecturer in politics and security studies at Perth’s Murdoch University, told news.com.au.

“It speaks to these kinds of bans. They are a form of political expediency and, when it becomes difficult, they end. Only when it looked like Prabowo was on the verge of winning the presidency in 2014, did the ban disappear.”

Australia reportedly only removed Prabowo’s name from its visa blacklist in 2014, ahead of the presidential election, to prevent embarrassment if the military general won.

Meanwhile, the United States quietly allowed Prabowo to return to its shores when he was made Defence Minister by Jokowi in 2020.

Over the years, there have been numerous allegations made against Prabowo including that, while serving in the Indonesian military, he led a fatal mission to Timor Leste in 1978 to capture the country’s first prime minister, Nicolau dos Reis Lobato.

He was also accused of commanding the special forces team responsible for the 1983 Kraras Massacre, also in Timor Leste, which killed more than 200 people.

In May 1998, Prabowo was accused of instigating riots across Indonesia, deliberately targeting minority Chinese-Indonesians when he was head of Indonesia’s Special Forces Command known as Kopassus.

During the riots, which human rights activists maintained were designed by the military to divert attention from the disastrous Asian Financial Crisis and calls for then-president Suharto’s resignation, looters took to the streets across Indonesia and set upon Chinese-owned businesses, ransacking them and killing, beating and raping thousands of Chinese-Indonesian men and women.

As protests against Suharto continued to bloom across Indonesia, students at Jakarta’s Trisakti University staged demonstrations, leading to members of the military shooting four students dead.

A further 22 student activists were abducted, allegedly on Prabowo’s orders, and 13 were never found, although Prabowo was never tried in court and instead went into self-imposed exile in Jordan as a guest of King Abdullah.

Now that he has finally secured Indonesia’s top job, some fear that Prabowo will rule the world’s third-largest democracy with an iron fist and plunge the country back to the New Order years, when former president Suharto ran a dictatorship from 1968 to 1998 which stifled political opposition and any criticism of the government.

Judith Jacob, director of geopolitical risk and security intelligence at risk management company Forward Global, told news.com.au that “Prabowo is in many ways the embodiment of Indonesia’s cartel party system. A system where a small group of elites share the spoils of governing power, regardless of what political party they belong to”.

Prabowo himself comes from a prominent political family, and his father, the well-known economist Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, was a minister under both former presidents Sukarno and Suharto. In 1983, Prabowo married Suharto’s daughter, Siti Hediati Hariyadi, before the pair divorced in 1998.

“His backstory is in many ways in keeping with the elite political class in Indonesia. He comes from a powerful family, he is part of the military and subsequently the governing establishment,” Jacob said.

In 2019, despite having lost the election to Jokowi, Prabowo was named Defence Minister in a move that some felt served to distance him from his alleged violent past.

“This association with Jokowi helped to rehabilitate his image as a hardliner and to seed in the public [consciousness] notions of competence, good leadership, and that he is ultimately working for all Indonesians,” Jacob said.

Prabowo doubled down on this message when running for the presidency in 2024, with a campaign promise to grow Indonesia’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 8 per cent and tackle poverty and stunting in children by starting a new free school lunch program, which will be rolled out in 2025.

Yet some Indonesians refuse to forgive or forget the past.

“Prabowo is ambitious, opportunistic, temperamental and cruel,” Indonesian activist John Muhammad told news.com.au.

“He will lead Indonesia in an authoritarian manner. He has run for the presidency numerous times which demonstrates his political ambitions, and his opportunism can be demonstrated by his decision to leave the opposition and join Jokowi’s cabinet as Defence Minister in 2019. “His temperamental attitude can be traced back to various public appearances, especially before 2019.”

Over the years, Prabowo has been known for flamboyant public speeches, appearing at events in khaki safari shirts and sunglasses, often while on horseback, and complaining about “foreigners” and unspecified “foreign interference” in Indonesia.

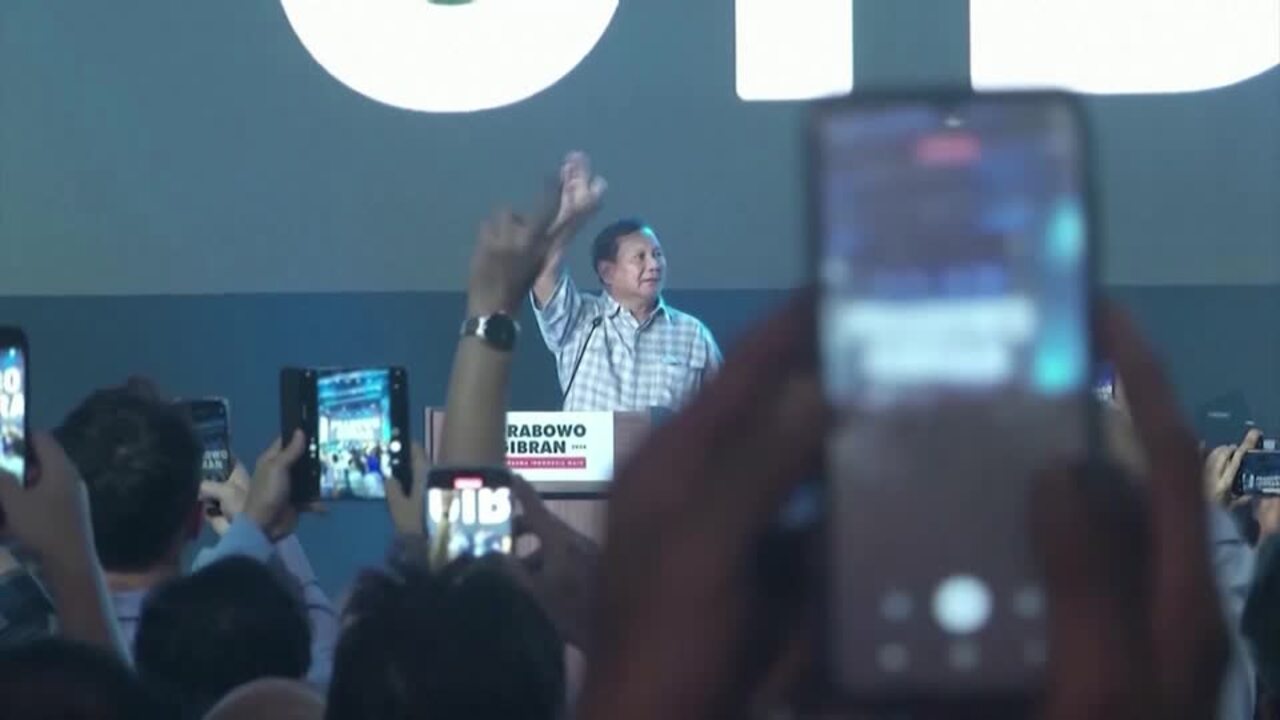

He sought to paint himself in a more sympathetic light during his 2024 election campaign, however, adopting the moniker “Si Gemoy” or “The Cutie” and dancing on stage at rallies.

In May this year, however, shortly after winning the election, he described democracy as “messy and tiring” and said that Indonesia would “not be determined by foreign narratives, foreign interpretations of what democracy should look like”.

Murdoch University’s Dr Wilson said that Australia’s relationship with Indonesia in the future would likely focus on mutual co-operation such as joint military training exercises, in keeping with Prabowo’s background as a decorated military man.

“Former president Jokowi was never comfortable on the international stage in the way that Prabowo will be,” he said.

“Joint military exercises between Indonesia and Australia will now likely be more energetic, and Prabowo will want to do that kind of engagement and put Indonesia on the world stage.”

Originally published as Chilling past of Indonesia’s new President Prabowo Subianto exposed