Quiksilver riding a new wave

WITH a lifelong love of surfing, Greg Healy is driving a recovery at Quiksilver. Jeff Whalley reports

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

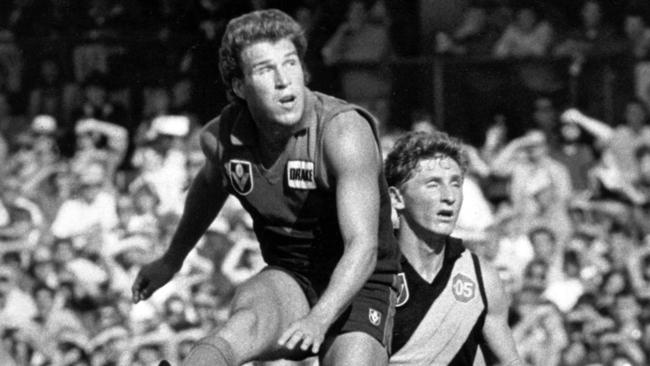

BEFORE he donned the No.33 for the Melbourne Football Club, Greg Healy was just a boy who loved to surf.

During chilly Victorian winters he would hear stories from the early days of the sport, when the blokes of Sorrento and Gunnamatta surfed in their old woollen footy jumpers.

That was before the evolution of wetsuits as they tried to ward off the cold.

“My brother (Brownlow Medal winner Gerard) and I grew up surfing the east coast from when we could stand up,” Healy tells Business Daily.

“I’d heard the stories ... it just shows you how passionate they were, and they just loved the sport.

“It’s just a great example of the need for innovation — whether it’s ... a footy jumper or (a genuine) wetsuit, people just need these products to help them enjoy the sport they are trying to participate in.”

Healy’s passion for the water continued through his 141-game career at Melbourne, “to the frustration of coaches at the time” who worried he would be injured in the waves.

After his playing days, his hobby became his career, running Quiksilver’s Asia-Pacific arm, and 18 years later, he was tapped on the

shoulder to take over the group’s floundering US operations.

Healy became group president — akin to chief operating officer — at the same time as Quiksilver Europe head Pierre Agnes was made chief executive last year.

The past year has been as difficult as anything Healy faced as captain of the Demons in the late 1980s.

Within five months, the US division filed for bankruptcy as it buckled with an $US800 million ($1.07 billion) debt in a tough consumer market.

It only emerged from the process in January after Healy helped strike a deal with US private equity house Oaktree Capital Management, which now owns the rights to key Quiksilver brands.

The problems that beset the surf brand fashioned in Australian garages in the 1960s and ’70s are well known.

As surfing evolved from a niche sport to an international pastime, the likes of Rip Curl and Quiksilver (Torquay) and Billabong (Gold Coast) grew into global operations.

Oaktree was already a familiar presence among the Australian-born surfwear labels, investing heavily in Billabong three years ago and breathing new life into it.

The question is where the cash in the action sportswear industry — as it is now called — will come from in future.

Healy, who went to Monash Uni, says Quiksilver, Billabong and Rip Curl were ostensibly apparel brands.

But he says to keep their credibility, they needed to

also have “meaningful” offerings in hard goods — surfboards, snowboards and snow boats.

“People need to buy 10

T-shirts a year, but probably only buy one surfboard a year,” Healy says.

“We know the majority of our consumer is aspirational — there’s only probably 10 per cent that are hardcore participants in the sport.”

The greatest growth is in the emerging health-focused demographic, characterised by brands such as Lululemon, which makes clothes for exercise that are becoming popular as leisurewear.

Roxy, a Quiksilver brand focused on young women, has just launched its fitness line aiming to capitalise on the trend of going for walks or to yoga and then cafes.

He says there is “significant growth” expected among both women and men, not only in traditional western markets but in areas such as Asian countries with a rising middle class, particularly China, Taiwan and Korea.

“The more the emerging economies have the ability to participate in the sport, I think that is an opportunity for us,” Healy says. Quiksilver’s operations in Torquay have the role of building its brands in those emerging Asian markets.

That process is underway; Quiksilver has sponsored a surf contest in China, and DC Shoes sponsored skater Danny Way jumping the Great Wall of China.

And surfing in Indonesia is no longer dominated by Australians, Healy says.

“If you go to Bali right now, you will be battling to get a wave off Indonesian kids,” he says. “I love it.”

One day, the industry may also see a “Chinese Kelly Slater”, and “hopefully he is (signed) under Quiksilver”.

The company’s future in Torquay has been a subject of conjecture as Quiksilver is increasingly globalised.

The group’s headquarters are now at Huntington Beach in California, where Healy lives, and apparel is designed in St Jean de Luz in western France.

Torquay has a significant sales force and its own product managers to ensure the domestic offering is relevant, as well as running the

Asia-Pacific business.

Healy says one of the great challenges the industry has had is it “grew up as a (series of) domestic businesses”.

“Given challenges we’ve all had, we’ve had to globalise,” he says.

“But, importantly, to make that work we’ve got Australian designers there, we’ve got Japanese designers there, so it’s a real international hub.”

Healy says Torquay will not be hollowed out, but the company needs to “embrace the change” and “make sure we execute correctly”.

But the company still has work to do, which could mean driving the enterprise harder.

“There will be efficiencies to be looked at, to be gained, from every office in the world — the Torquay office, the Japanese office will all participate in the areas we are trying to improve,” he says.

“We are looking to keep Australia strong, but as a global business we need to get more efficient and do things better.”

The industry faces a fresh challenge, with many new surf companies — some started by ex-Quiksilver designers — chasing the big players.

Emerging brands such as sunglasses house Valley and wetsuit maker Need Essentials were set up by former Quiksilver designers for the group.

Healy’s first US priority is fixing the distribution network — thousands of independent surfwear and apparel shops carry Quiksilver.

“They are partners we have done business with for the last 40 years and we need to be meaningful to them,” he says.