Fears mount over the cost to Australia of China’s worsening economic ‘crisis’

Beijing is battling a “crisis” that has gone from bad to worse and sparked panic in Australia about the ultimate price we might have to pay.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The saying goes that when China sneezes, Australia catches a fiscal cold – and if that adage holds true now, some fear our economy is in for an especially nasty illness.

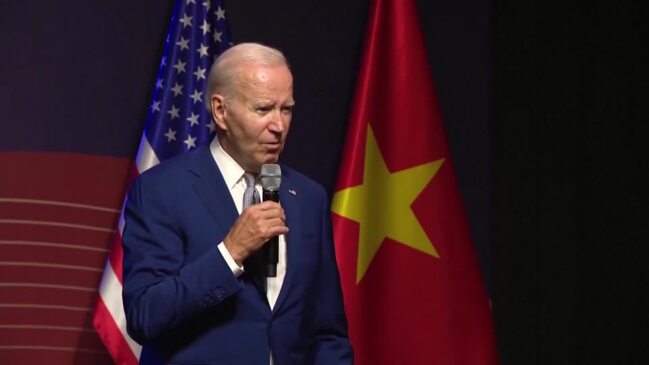

Concerns about the precarious state of China’s economy are growing, with US President Joe Biden describing the situation as “a crisis” at the weekend.

Here, Treasurer Jim Chalmers has admitted he shares “pretty substantial concerns people have” about China’s economy, describing recent weakness as having “obvious implications for us here in Australia”.

“In China, they’re dealing with slowing growth, they’ve got deflation, there are concerns in their property sector, and to some extent in their banking sector, and their exports have slowed as well,” Dr Chalmers said.

“And so a lot of people around the world, a lot of economists, a lot of partners around the world, are watching developments in China very closely, as I am.”

Beijing is battling a decline in private investment, widespread issues in the property sector, high youth unemployment, skyrocketing debt and weak exports.

The end of draconian ‘zero Covid’ containment measures was expected to spark an economic recovery this year.

Instead, Professor Adam Tooze from Columbia University told the Wall Street Journal: “We’re witnessing a gearshift in what has been the most dramatic trajectory in economic history.”

The International Monetary Fund puts China’s gross domestic product growth below four per cent in the coming years.

British firm Capital Economics is less optimistic and sees trend growth at around three per cent, down from five per cent pre-Covid in 2019. It forecasts a fall to two per cent by 2030.

According to analysis by think-tank The Lowy Institute, China’s woes “may well get worse before they get better”.

“Growth has slumped, crucial parts of the economy are in bad shape, youth unemployment is rising, and consumer and producer prices have been falling,” it said.

Not too long ago, China was meant to overtake the US as the world’s economic superpower – a milestone that was meant to be met by now.

In its latest analysis, Bloomberg predicts “it may never pull ahead to claim the top spot”.

At best, Bloomberg Economics forecasts it will take until the mid-2040s for China’s GDP to surpass that of America – but only by “only a small margin” and fairly briefly, before “falling back behind.”

Should Australia be worried?

Nicolaas Groenewold from the University of Western Australia has modelled the likely long-term impact on Australia’s economy of a sustained slump in China’s growth of three per cent.

“Estimates … suggest the effect on Australia of a permanent fall … will be to reduce Australia’s growth rate by about 0.2 percentage points in the short run and approximately 0.5 percentage points in the long run,” Mr Groenewold said.

“While not trivial, given Australia’s current growth rate, these estimates are hardly enough to justify prophesies of doom.”

Separate modelling by the Reserve Bank reached a similar conclusion. Its analysis found a four per cent fall in China would result to a midterm drop in Australia’s GDP of 0.3 per cent.

James Laurenceson, director of the Australia-China Relations Institute, believes concerns about the impact on the local economy are overplayed.

“There has never been a straightforward, one-to-one relationship between the ups and downs of economic activity in China and those in Australia,” Mr Laurenceson wrote in The Conversation.

Australia’s economy has what he calls “in-built automatic stabilisers’ that limit spill overs from China.

“If there ever was a collapse in Chinese demand for Australian iron ore, the Australian dollar would immediately depreciate, improving export competitiveness across the board,” he said.

“There would still be some painful costs, of course, such as households having to pay more for imported goods, and government revenues taking a hit.”

And while China is Australia’s largest and most important export market, its value amounts to about 7.5 per cent of GDP, he said.

“Compare that with domestic sources of demand such as household consumption that stand at 50 per cent of GDP.”

Originally published as Fears mount over the cost to Australia of China’s worsening economic ‘crisis’