Australia’s biggest export on the brink of $30 billion loss

Australia’s biggest earner faces an uncertain future which could see $30 billion wiped almost overnight.

Mining

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mining. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ANALYSIS

Australia’s biggest earner faces an uncertain future. “Dig it and ship it” won’t cut it anymore. And if we don’t add “refine it” to the iron ore equation within just 20 years – global steelmakers will take their chequebooks elsewhere.

Iron ore is Australia’s largest export earner at $131 billion last financial year. But that’s projected to fall to about $100 billion in 2024 to 25. And, unless action is taken to reinvent the industry, that decline is expected to only accelerate.

That’s bad news for Australia’s de-industrialised economy.

“Our competitors – countries such as Brazil and Guinea with higher-grade ores in relative abundance – are positioned to become the steel industry’s suppliers of choice,” warns RMIT University lecturer and Wuhan University of Science and Technology adjunct professor Dr Charlie Huang.

That’s because they can offer the world’s steelmakers what they need: an off-ramp in the face of rapidly escalating global tariffs designed to punish carbon dioxide emitting industries.

But buying the highest-grade hematite (iron ore usually eroded out of the landscape and precipitated in ancient oceans) – is mostly about signalling intent, says Magnetite Mines Ltd CEO Tim Dobson.

“Putting a higher grade iron ore in a blast furnace does reduce the carbon footprint marginally. But it doesn’t go anywhere near meeting mandated targets,” he explains.

The fact is, the global steel industry is being forced to find alternatives to blast furnaces to cut emissions. And the most viable technologies cannot handle the waste slag generated by even the highest-grade natural ores.

“Future iron powerhouse producers will be those that can purify the most ore in the cheapest – and greenest – ways possible,” Dobson says.

For Australia, that’s either an opportunity – or a disaster.

And that, industry leaders and analysts say, is why Australia needs to build a new iron economy. Fast.

A burning need

“The Australian iron ore industry faces a major challenge as its biggest customers – China’s steel mills – move to drastically reduce their carbon footprint,” warns Dr Huang.

Despite China’s building industry downturn, long-term global outlooks for steel remain strong. As developing nations like India industrialise and established economies seek to replace ageing – and polluting – infrastructure, some analysts foresee growth of up to 25 per cent by 2050.

But the high carbon dioxide cost of the current steel industry threatens to put the brakes on this.

It’s responsible for between 6 and 9 per cent of all global emissions. It takes enormous amounts of heat to smelt bulk iron ore into steel. And the less pure the ore, the more smelting is needed to make the grade.

But burning coal to fire those furnaces is no longer a long-term option. Especially as the world may have already exceeded 1.5C in global warming because of the thermal blanket effect of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Solutions are being sought. And being found. But the quality of Australian iron ore is part of the problem.

Europe, for example, is establishing import tariffs against “dirty” products – including steel – to balance out the greater costs its own low-emission manufacturers must bear.

And Beijing has, in recent years, already been seeking to reduce its reliance on Australian iron ore. Now, it’s looking towards “greener” pastures as a first step in adapting to Europe’s stringent standards.

That has profound implications for Australia’s iron-addicted economy.

China buys 85 per cent of all iron ore mined here. That represents about 60 per cent of the total it consumes.

Australian miners – and Canberra’s export earnings – are therefore immensely vulnerable to Chinese political and economic fluctuations.

“Australia could adapt its production to meet this change in demand. But if it doesn’t do so quickly, it may find itself left behind in the new green economy,” notes Dr Huang.

The changing colour of steel

Most of the world’s steel is currently made by heating coal to create coke, which is then fed into blast furnaces to boost temperatures above 1800C.

As a rule of thumb, 1.9 tonnes of carbon dioxide is emitted to produce one tonne of molten steel. But Dr Huang says smelting one tonne of low-grade Australian ore can emit more than 200kg more than high-grade Brazilian ore.

“A high level of impurities in low-grade ore also significantly reduces the efficiency of the process,” he adds.

Bulk ore shipments out of Brazil and Guinea generally contain about 65 per cent iron. Australian ore now varies anywhere between 56 and 62 per cent.

“Steel makers, particularly the Chinese, have figured out how to continue to make quality steel out of lower and lower grades over time,” adds Dobson. “But it has come at a great carbon cost because of the extra coal that has to be used.”

And despite decades of research and experimentation, the steel industry remains far from rolling out an alternative to coal for the chemistry and heat needed in traditional blast furnaces.

“A number of new and emerging steelmaking technologies offer the promise of significantly lower emissions,” says Dr Huang. “But common to all of them is a need for higher-grade iron ore than Australia produces.”

Direct reduction iron (DRI) shaft furnaces are a proven method. They’re used to produce industrial grade iron by nations with ready access to ample methane gas. And it’s a technology that can be adapted to burn green hydrogen – once supplies become available.

But to produce steel these furnaces need pre-processed iron ore pellets with purity levels above 67.5 per cent – higher than even the best natural hematite deposits.

Dig it. (Beneficiate it). Ship it

Australia has vast, untapped reserves of magnetite iron ore. This is formed as cooling magma crystallises.

It has a lower iron content than hematite (generally between 30 and 40 per cent). And purifying it (a process called beneficiation) is an energy intensive process.

In the past, when competing with high-grade “direct shipping ore” from hematite deposits, that cost has made it a less economically viable option.

But, unlike hematite, magnetite is magnetic. That’s put it back in the running as the most viable source of purified iron for green smelters.

“With the push to DRI technology, there’s nowhere near enough magnetite available at the moment,” says Dobson, whose Adelaide-based company is developing a high grade iron ore project in South Australia’s Mid North. “And most of what is being produced isn’t yet being pushed up to the very high grade needed for arc furnaces. So it’s still going into blast furnaces”.

Magnetite’s economic viability still needs a “carrot and stick” approach, he adds.

Europe is leading the way with carbon taxes and carbon tariffs. And this is putting pressure on the rest of the world to follow suit in order to protect their own industries.

“The carrot part is customer demand,” Dobson explains. “There are already European car manufacturers that are willing to pay more for green decarbonised steel. The best recent example was one that paid 200 euros a ton over and above the benchmark steel price.”

Beneficiating magnetite also represents a significant shift from Australia’s hematite ore exports’ “dig it and ship it” mentality.

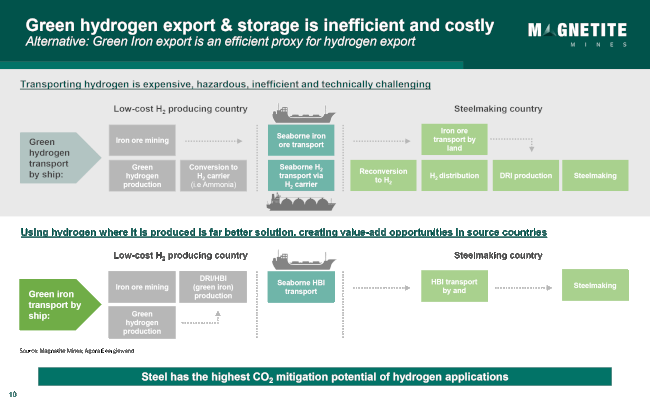

Magnetite needs massive amounts of hydrogen to refine.

That means purified ores are best produced in locations with easy access to both high-quality ore and abundant renewable energy for electrolysing water into hydrogen and oxygen.

Such “value adding” dramatically cuts transportation costs (and carbon emissions) as only purified iron pellets need to be shipped to global steel making foundries.

“But this needs a massive outlay in renewable energy to take advantage of our natural resources,” Dobson warns.

Energy – at scale

“There has been much hype around Australia’s potential to produce cheap hydrogen with renewable energy. But if we pull it off, we could stand at the forefront of the green steel revolution as a global production hub of direct reduced iron,” says Dr Huang.

But electrolysis demands a lot of electricity.

And iron ore beneficiation would require hydrogen to be manufactured on a mind-boggling industrial scale.

“You can be incredulous about the scale of this,” Dobson says of the need for hundreds of square kilometres of solar panels and wind farms to drive a hydrogen economy. “But this evolution is not going to take place overnight. It will take two to three decades. But we will need to be ramping up and rolling out transmission networks, solar farms and wind farms continuously if we’re going to take advantage of this opportunity.”

Nuclear energy is an option, but Dobson says the politicised nature of the debate and the extended time frame necessary for design, approval, and construction puts it beyond helping the iron ore industry transition before 2050.

“The expansion of this new industry is going to be fast – even if we’re not,” he explains. “And our output will only be as fast as how much renewable energy we can bring online and how quickly we build our own DRI plants. It’s a huge investment.”

While the entirely new hydrogen production economy is only just beginning to get off the ground, Dobson says natural gas can help plug any production gaps. This will steadily switch over to hydrogen as the industry matures.

“The key point, I guess, is that both Western Australia and South Australia have massive magnetite reserves. And we have huge potential that other nations don’t have for renewable hydrogen. But to keep our iron ore earnings, we’re going to have to make some serious and fast changes,” he concludes.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as Australia’s biggest export on the brink of $30 billion loss