Yellowstone supervolcano shift stirs fears of eruption

Scientists say the enormous Yellowstone supervolcano is stirring in its sleep, with concerns the subterranean monster could blow.

The Yellowstone supervolcano is stirring in its sleep. Scientists say the enormous magma pool is moving.

Researchers from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) have been probing the subterranean monster lurking beneath America’s idyllic Yellowstone National Park and its surrounds.

It’s an untouched wilderness surrounded by scenic, ice-capped mountains. Its spectacularly colourful hot pools and geysers attract tens of thousands of visitors every year.

It’s also one of the largest volcanoes on Earth.

The Yellowstone Caldera is a 70 by 45 kilometre-wide crater in northwestern Wyoming, blasted out of the Earth’s crust some 640,000 years ago in a cataclysmic eruption.

It was an Earth-shaking event. Literally.

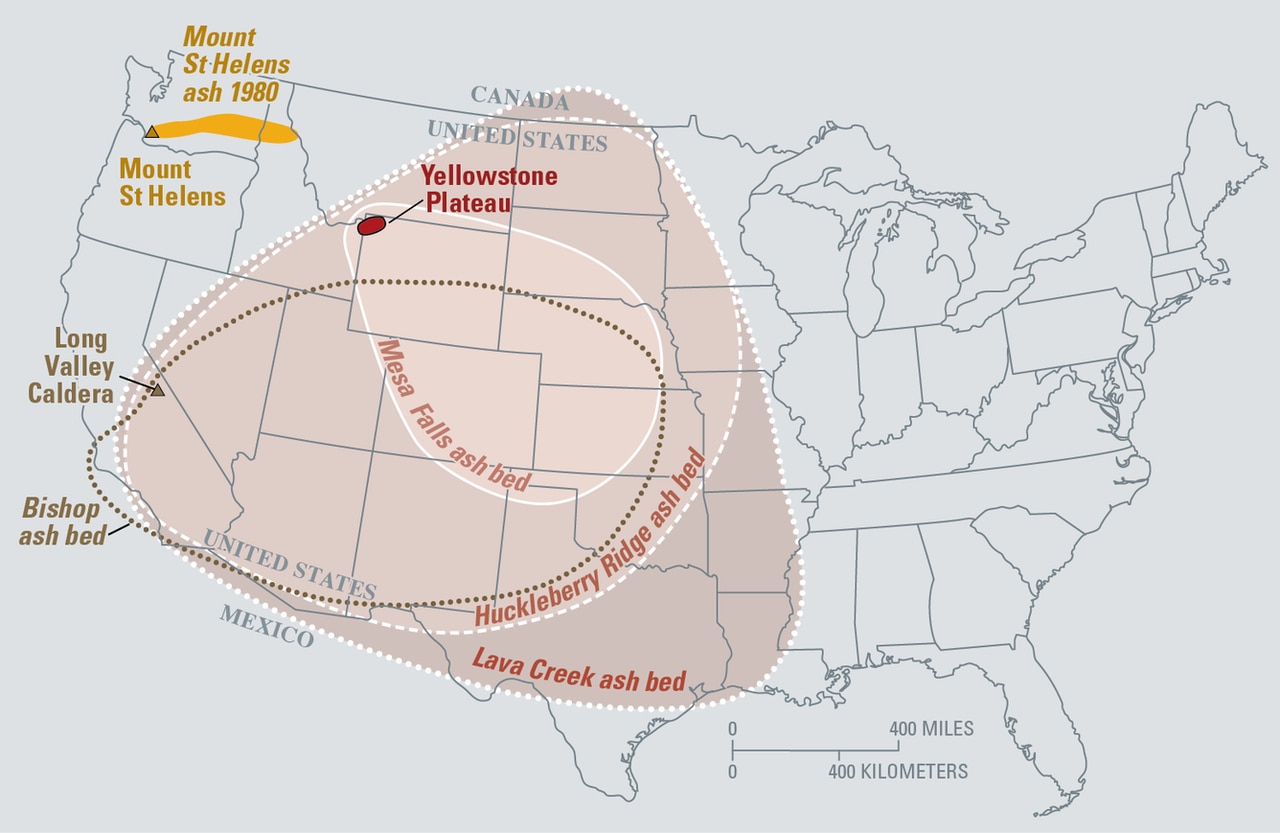

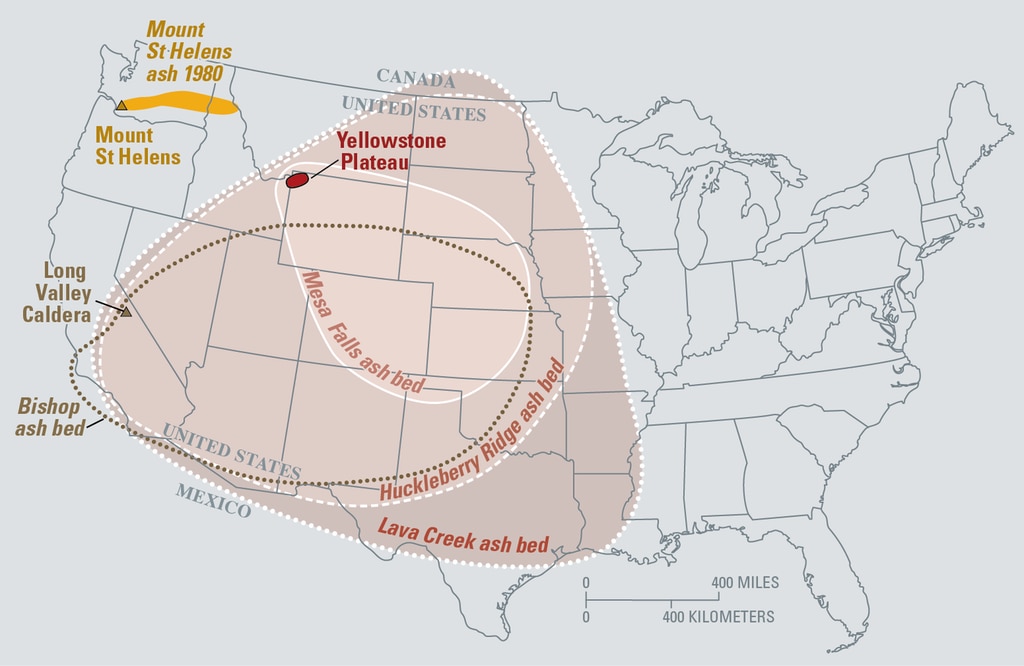

Vast quantities of searing lava and clouds of toxic ash swept across the North American landscape. Geological surveys reveal much of what is now the United States was smothered by ash. And rivers of molten lava streamed out of Yellowstone for hundreds of kilometres, sometimes settling in pools several kilometres deep.

This outpouring of gas, smoke, ash, and debris changed the climate of the entire planet for several centuries.

Naturally, scientists want to know when this is likely to happen again.

And a new study is helping paint a picture of the beast that lurks beneath the beauty of Yellowstone Park.

An apocalypse named Yellowstone

Every 700,000 years or so, the Yellowstone supervolcano erupts.

And it does so with a whoosh. Not a bang.

The supervolcano is not the enormous mound of ash and lava you see in school textbooks.

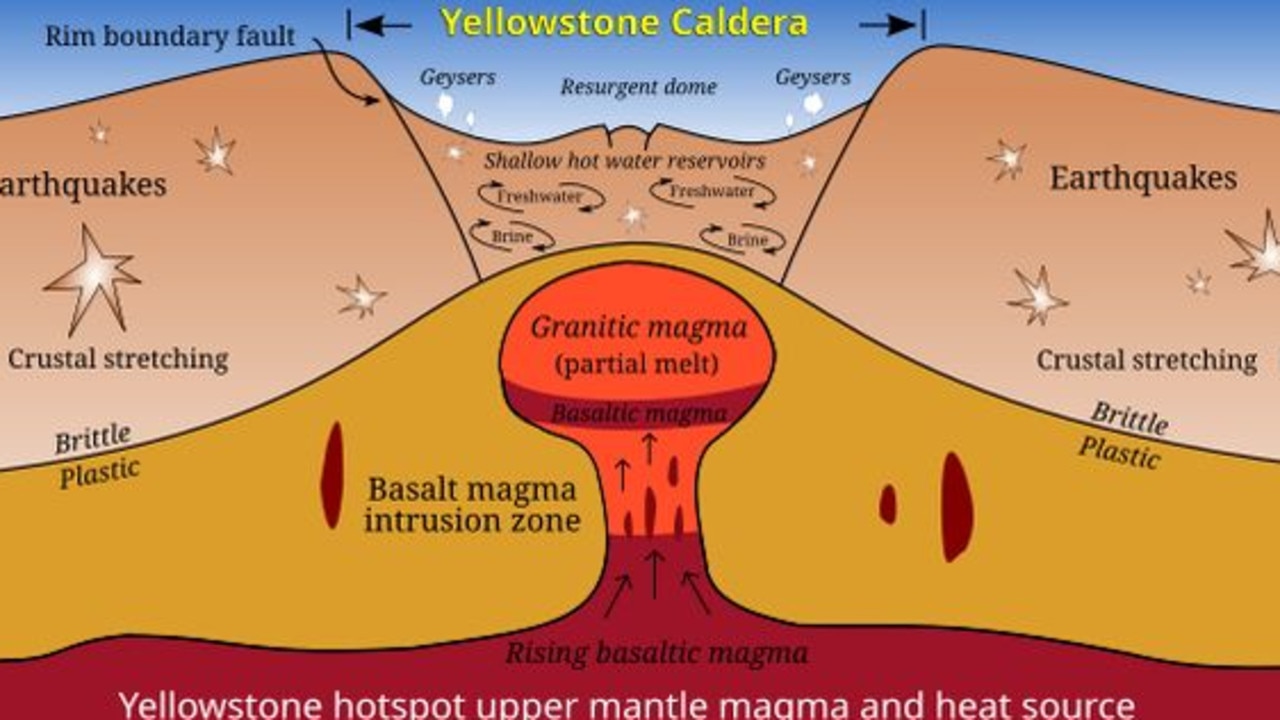

Instead, it’s a massive pool of magma sitting just under the earth’s crust

An eruption is when that crust collapses into the rising magma, which boils over to the surface.

Geologists have identified three separate Yellowstone calderas left by past volcanic events. A caldera is hollow which is most usually left after an eruption empties an underground chamber of its magma.

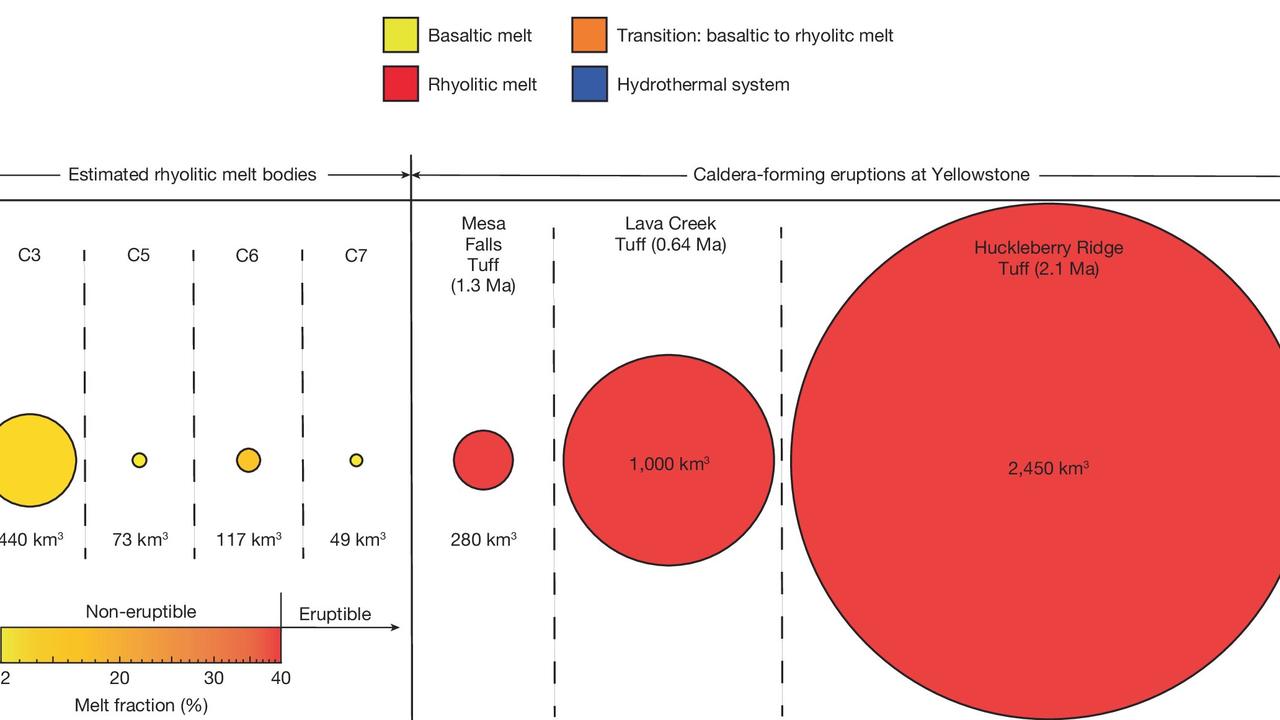

The Huckleberry Ridge eruption took place some 2.1 million years ago and formed a large caldera. The second (Mesa Falls) was 800,000 years later. The third, centred on Lava Creek Tuff and dated to some 650,000 years ago, defined much of the region’s terrain as it is known today.

But the supervolcano does not sleep deeply.

A small eruption (at West Thumb) is believed to have occurred as recently as 150,000 years ago. And an explosion some 13,000 years ago left a crater at Mary Bay on the edge of Yellowstone Lake.

Researchers have been attempting to peer beneath the surface for decades to “see” what the subterranean molten magma pools are doing.

But the area’s complex geography has made that difficult.

Geologists have long since identified two resurgent magma domes – where the Earth is pushed up by the pressure of the molten rock – north and west of Yellowstone Lake at the caldera’s heart.

But thermal sensing techniques have been confused by the networks of steam vents (geysers) that make the pristine national park such a tourism magnet. And seismic probes have had to contend with the supervolcano’s pancake-like layers of old lava.

Now, USGS seismologists have been monitoring variations in the electromagnetic fields in and around the supervolcano to infer what’s happening below.

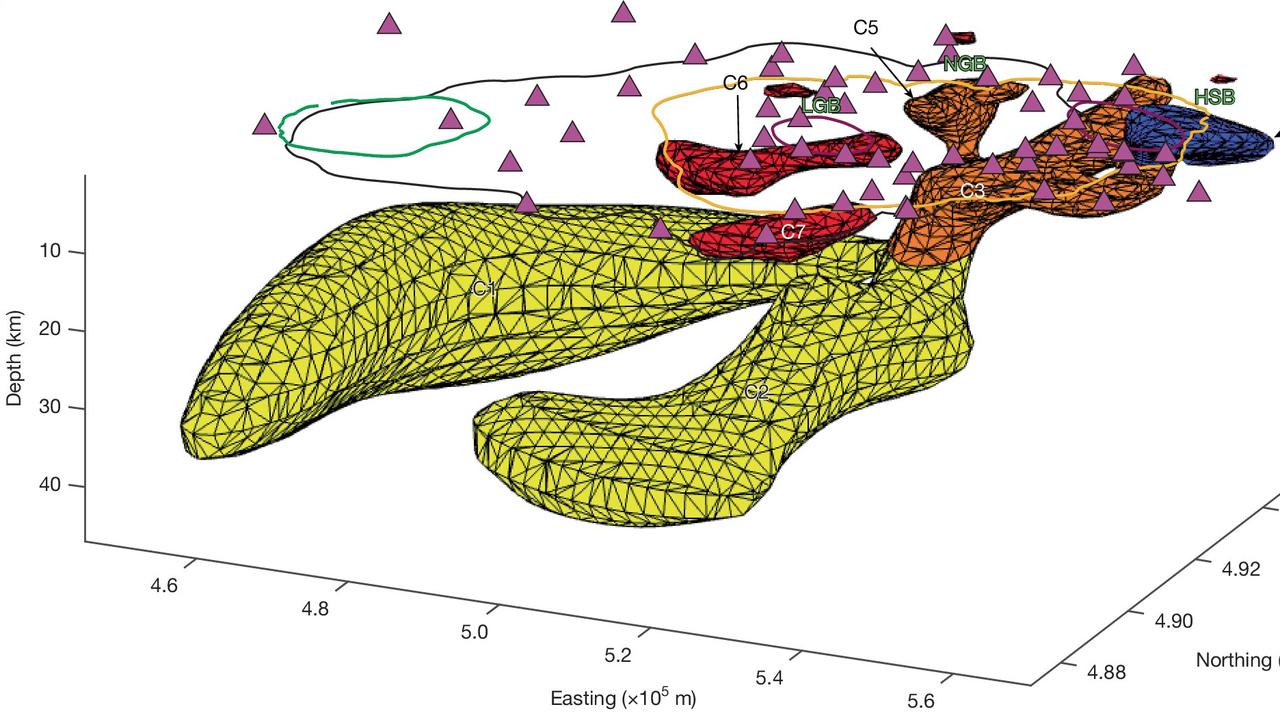

They’ve found 388 to 489 cubic kilometres of molten rock sitting relatively close to the Earth’s surface under the park. But different types of magma conduct electricity differently. And that helps “diagnose” the volcano’s current state of slumber.

Where monsters lie

Yellowstone is recharging. But the study indicates it’s still far from an earth-shattering eruption.

Instead, it will continue to sleep restlessly for some time to come.

The USGS scan results show at least seven distinct concentrations of magma, with some appearing to be linked.

Their depths vary. The deepest is about 47km beneath the surface. The shallowest is just 4km.

But it’s the differences in the magma that is most telling.

Basalt magma is highly mobile and wells up from the mantle deep beneath the Yellowstone hotspot. It’s also dense and contains concentrations of magnesium and iron.

Rhyolite melt is thicker, slower-moving molten rock. It contains far more silica than basalt magma. And it’s generally associated with explosive eruptions.

The USGS survey reveals the relationship between them.

Huge reservoirs of basaltic magma in the lower crust are heating chambers of rhyolitic melt in the upper crust. These are now concentrating in Yellowstone’s northeast.

“We identify regions of basalt migrating from the lower crust, merging with and supplying heat to the northeast region of rhyolitic melt storage,” the researchers write.

“On the basis of the volume of rhyolitic melt storage beneath northeast Yellowstone Caldera, and the region’s direct connection to a lower-crustal heat source, we suggest that the locus of future rhyolitic volcanism has shifted to northeast Yellowstone Caldera.”

And the near-surface rhyolite fills a volume of about 440 sqkm

“Seismic tomography studies have suggested that a broad region of rhyolitic melt extends beneath Yellowstone Caldera, with an estimated melt volume that is one to four times greater than the eruptive volume of the largest past caldera-forming eruption,” the study notes.

That figure sounds ominous.

“The largest region of rhyolitic melt storage, concentrated beneath northeast Yellowstone Caldera, has a storage volume similar to the eruptive volume of Yellowstone’s smallest caldera-forming eruption,” the study states.

But while the new concentrations of magma in Yellowstone’s northeast are significant, they’re not the biggest it’s ever seen. And they’re broken up.

“We find that rhyolitic melts are stored in segregated regions beneath the caldera with low melt fractions, indicating that the reservoirs are not eruptible,” the study concludes. “Typically, these regions have melt volumes equivalent to small-volume post-caldera Yellowstone eruptions.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as Yellowstone supervolcano shift stirs fears of eruption