Novak Djokovic as the opposite of a religious experience

Novak Djokovic has achieved more than anyone in tennis. He’s eclipsed his biggest rivals. But one thing still eludes him, and always will.

Aus Open

Don't miss out on the headlines from Aus Open. Followed categories will be added to My News.

COMMENT

When Novak Djokovic retires, probably at the age of about 57 (presuming his superhuman knees and lungs do finally degrade to the level of a mere mortal by then), I will not miss him. Not even a little. And I’ve been trying to figure out why.

This guy is indisputably the best tennis player ever. He could have quit three years and as many grand slam titles ago having already settled the debate. He does things with a racquet that defy sense and, sometimes, seem to break the laws of physics.

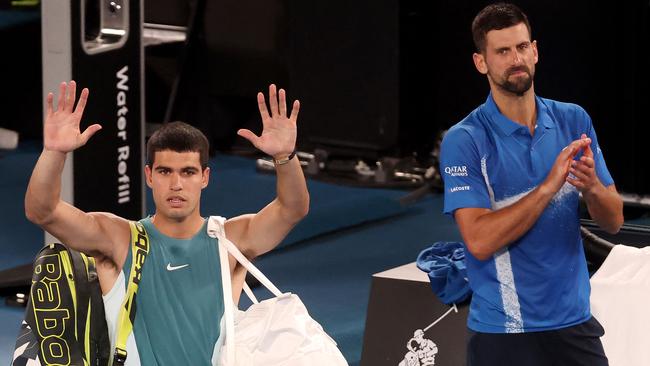

The 37-year-old defeated Carlos Alcaraz in four sets in the quarterfinals to keep his dream of an 11th Australian Open title and a recordbreaking 25th grand slam alive.

It should feel like a fading privilege to watch someone who wields such astonishing talent. Djokovic’s few remaining seasons should feel precious. Why then do his appearances on court elicit a similar emotional response to, say, unloading the dishwasher?

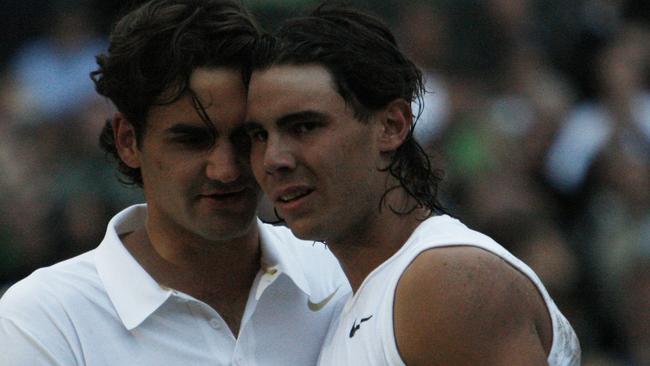

It’s not a partisan thing, at least not entirely. I always barracked, with ever-mounting desperation, for Roger Federer over Rafael Nadal, and quite resented the Spaniard for having seemingly been bred in some secret Mallorcan lab for the sole purpose of beating him.

The closer Nadal came to Federer’s grand slam tally, the more entrenched became my irrational (and yes, nakedly unreasonable) opinion that being essentially unbeatable on one surface was unfair, and almost amounted to cheating.

But I do genuinely miss Nadal. I miss those strange little idiosyncrasies, like his refusal to step on the court’s lines or the habit of picking his undies out of his bum before each serve. I miss the sight of that unique, booming forehand, with its characteristic MS Dhoni-like flick during the follow-through.

And much as it bothered me at the time, I now miss watching Nadal pummel and torment Federer year after year. It was always compelling, that clash of Federer’s inconsistent grace and Nadal’s brute determination, in a way that Djokovic’s metronomic perfection is not.

Back in 2006, David Foster Wallace published probably the most celebrated piece of sport writing in memory, headlined “Roger Federer as Religious Experience”. This was at the apex of Federer’s then-unprecedented, imperious reign over tennis, before Nadal (and eventually Djokovic) surpassed him.

“Federer is showing that the speed and strength of today’s pro game are merely its skeleton, not its flesh,” David wrote.

“He has, figuratively and literally, re-embodied men’s tennis, and for the first time in years the game’s future is unpredictable.

“Genius is not replicable. Inspiration, though, is contagious and multiform. And even just to see, close up, power and aggression made vulnerable to beauty is to feel inspired and (in a fleeting, mortal way) reconciled.”

Some lovely sentimental writing there; come to think of it, you would probably be better entertained if you went and read David’s piece instead of this one.

He compared Federer to other preternaturally gifted athletes like Michael Jordan and Muhammad Ali, who seemed to warp time and space around them. The closest comparison, for me, has always been the New Zealand rugby player Dan Carter, who operated in slow motion without ever running out of time.

Carter happens to be the highest point-scorer in the history of Test rugby, but what I’m talking about here would be no less true if he’d only played for one season. There really is something quasi-religious about witnessing these freaks of nature in flow, as though they’re on another plane of evolution from the rest of us.

Djokovic’s achievements belong in the same conversation, but the experience of watching him does not. He has all the skills, and an unparalleled record to vindicate them, yet somehow he’s ... mundane? Dull?

If, say, Justine Henin’s backhand was poetry (and it was), Djokovic’s is basic, competent, entirely unimaginative prose. You can say the same of his groundstrokes in general, and of his movement on court, and of his serve, and of the merciless way he grinds down his opponents. It’s all maddeningly efficient and effective. It just isn’t very interesting.

That doesn’t mean he’s bad at tennis, of course. No one on the planet is, or ever has been, better at it than Djokovic. But his game is an unmatched triumph of function over form, and that deprives the sport of its magic.

Federer’s tennis was otherworldly. Nadal’s was irrepressible. Watching Djokovic play tennis can feel a bit like looking over the shoulder of a particularly ruthless hedge fund manager as he compiles spreadsheets. They’re excellent spreadsheets! They’ve helped him make all the money imaginable. They’re not fun.

Even when he was losing, Federer would do maybe half a dozen things in each match that made you audibly gasp. You can watch Djokovic practising his particular brand of perfection for hours and hours, pulling off incredible shots and making almost no mistakes, without that happening even once.

You nod, you clap, you acknowledge that it’s all quite impressive. You might cheer if you’re Serbian, or someone of questionable taste. No gasping, though. Nothing that elevates Djokovic into the realm Wallace was describing.

And look, his personality doesn’t help. He’s the Aaron Rodgers of tennis: sometimes genial, sometimes prickly, always brimming with odd opinions. He’s an anti-vaxxer, as we discovered during Covid. A believer in “healing water”. His latest thing is a magnetic “energy disk” that supposedly helps with stomach inflammation.

He’s a weird guy, is what I’m saying.

Certainly, Djokovic is articulate and insightful enough to pursue the traditional post-playing career in commentary (his interviews are always excellent, too; easily the most successful part of his PR repertoire), but you get the sense he would be better suited to the bro podcast circuit, hanging out with Joe Rogan and RFK and spreading odd health theories.

There’s the way he rants to himself between points, or shoots crazy eyes at his coaches, or increasingly how he goads hostile crowds, as though fully embracing his role as a cartoonish WWE-style villain.

There’s his tendency to develop a limp or don an agonised grimace when the flow of a match is moving against him, while still managing to sprint and slide around as relentlessly as any other human being in the history of tennis.

None of these traits earn him much sympathy from the average fan. So we are left in an uncomfortable situation: Djokovic won the fight between the Big Three, eclipsing both Nadal and Federer, but he remains far less admired. His constant winning has become boring.

And having reached the summit of his sport, he is now becoming an obstacle to its success.

In the fading years of a great’s career, we would normally hope for more time, dreading the inevitable retirement. We’d want him to defy age and stave off the end a little longer.

Quite the opposite, here. We’re a bit done with Djokovic, aren’t we? And when he does leave, yielding the court to younger and more intriguing stars, the sport will be richer for it.

Twitter: @SamClench

More Coverage

Originally published as Novak Djokovic as the opposite of a religious experience