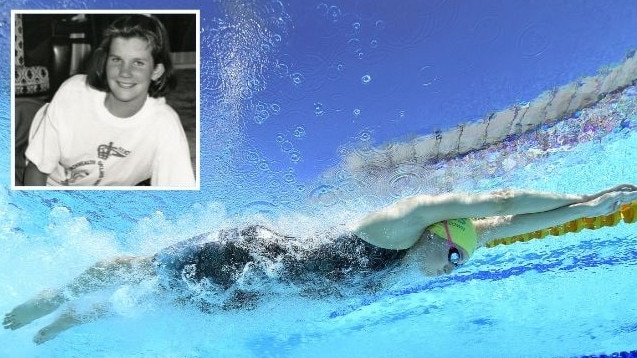

Jennifer McMahon shares her story of pain after years of abuse on Australian Swimming team

Jennifer McMahon had the world at her feet. Suddenly, she was drug dependent and broken following years of abuse on the Australian Swimming team. She's shared her story.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Addicted to sleeping tablets and using alcohol to drown her pain following years of abuse on the Australian Swimming team, Jennifer McMahon felt worthless.

The Commonwealth Games gold medallist and former world number 11 swimming champion, had stood with the world at her feet.

Suddenly, McMahon found herself standing at the end of the line at Centrelink with only $2 in her bank account.

Ashamed and broken – she would buy a 30 cent soft serve from McDonalds for dinner.

“I needed help,” McMahon said.

Kayo is your ticket to the best sport streaming Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

“I had many dark years dealing with the aftermath of swimming, scraping money together just to survive.

“It was after years of what I refer to myself as being a bottom dweller, that I decided I had to try education.”

That was 20-years ago – and McMahon is standing both defiant and informed.

McMahon is now a doctor at the University of Tasmania, after obtaining her PhD, centering her research around abuse in sport and athlete protection and wellbeing.

On Tuesday, McMahon choked back tears as she received her Order of Australia Medal (OAM) at Government House in Tasmania – recognition for her abuse education and contribution to sport.

At 15 and chosen on her first Australian team, McMahon was subjected to the torment of daily weigh-ins, weekly skin-fold testing, psychological abuse and non-contact physical abuse.

Concerningly, for some more than others within our favourite Olympic sports, they are coaching methods that still exist today.

The emotional scar-tissue of her swimming career was why McMahon chose to investigate the short and long-term effects of body practices on athletes.

“After graduating with first class honours and then a PHD, I realised that I was not alone in my experiences as a member of the Australian swimming team and there were many, many swimmers out there (like me) who were dealing with normalised forms of abuse which has short and long term effects,” McMahon said.

“When I was swimming, I learned from teammates that throwing-up after meals and taking laxatives were how they controlled their weight to avoid them getting in trouble by coaches and managers.

“I sat in the sauna for three hours the night before my (1991) world championship swim, petrified that team managers would follow through on their threats and kick me off the team if I put on weight again.

“I also tried throwing up the night before my world championship swim (recommended by a teammate). I was desperate to do whatever it took to make sure I did not get kicked off the team.

“I did not have another weight increase, the sauna and my attempts at throwing up worked, but my performance was obviously compromised.”

Her story is both a personal and professional warning to athletes, coaches and major sporting bodies that are frighteningly misguided to think Gymnastics Australia is alone in their failures to recognise abuse – of every kind – and their previously accepted coaching methods.

McMahon says Swimming Australia – and other major sports – that use in house reporting processes to investigate claims of abuse, instead of an independent tribunal or through Sports Integrity Australia’s national framework must change and that parents must take responsibility for turning a blind-eye to abusive coaching methods in the name of success.

Swimming Australia confirmed to The Sunday Telegraph that they are in the process of reviewing Sports Integrity Australia’s ‘National Integrity Framework’ and will decide if the sport adopts the policies in coming months.

“I applaud Gymnastics Australia for engaging the Australian Human Rights Commission to conduct an independent Review of the sport of gymnastics in Australia,” McMahon said.

“Gymnastics Australia have been proactive about reporting and have independent reporting authorities (Sports Integrity Australia and National Sports Tribunal).

“I recommend other organisations such as Swimming Australia do the same.

“Research tells us that abuse is happening across sports and across all levels, both amateur and elite.

“Research tells us that nearly 70 per cent of current athletes are experiencing neglect.

“Research tells us that just over 60 per cent of current athletes are experiencing psychological abuse.

While approximately 20 per cent are experiencing physical abuse and sexual abuse.”

McMahon has received funding from the IOC – in charge of implementing education and structure and encouraging sporting codes globally to adopt policies that protect athletes from abuse.

“The long-term impact of abuse on athletes is troubling which is why the International Olympic Committee have made it an urgent priority area that needs to be addressed,” McMahon said,

“The use of demeaning language towards an athlete’s body or body ridicule is psychological abuse.

“Excessive forced training to lose weight such as extra running is a form of non-contact physical abuse according to the IOC and other sport research.

“Putting an athlete on a severe diet is a form of non-contact physical abuse according to the IOC and sport research.

“Surprisingly, if you are a bystander and know that an athlete is engaging in problematic eating behaviour, but do nothing to intervene, you are complicit in physical neglect according to research.

“I experienced all of the above in regard to weight practices on the Australian swimming team, and my research shows it is still happening.”

McMahon, who won a silver medal in the 200m freestyle behind Auckland Games golden girl Hayley Lewis and gold in the 4x200m freestyle relay with Janelle Elford, Julie McDonald and Lewis, said parents played a major role in the protection of young athletes.

“It’s really important for parents to educate themselves,’’ McMmahon said.

“Look at what abuse in sport is and looks like according to the IOC definitions and examples.

“Recognising some of the signs or effects of abuse as athletes themselves might not recognise what is happening to them is indeed abusive but parents can recognise some of the signs like depression; not wanting to attend training sessions, weight loss, change in sleeping habits; becoming recluse,

change in mood; anxiety.

“It’s important for parents to not fall for mantras from coaches such as “trust the process; I have achieved great results with this method; I use this approach to build toughness.’

“The coach may have achieved great results with one of two athletes, but how many were damaged in the process and what have been the lasting effects?”

More Coverage

Originally published as Jennifer McMahon shares her story of pain after years of abuse on Australian Swimming team