Hand-me-downs and heart: How the Matildas broke down barriers, upset Brazil at 1988 ‘pilot’ World Cup

Australians emptied bank accounts and borrowed kit to take part in the ‘pilot’ event that convinced FIFA to stage a Women’s World Cup. ADAM PEACOCK revisits the momentous trip to China with help from some greats.

World Cup

Don't miss out on the headlines from World Cup. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Machine guns and locusts.

Hand-me-down playing kits that had to be returned. But weren’t.

Empty bank accounts and full hearts.

The story of the first ever ‘World Cup’ experience for an Australia women’s football team in 1988 is about as far removed from the modern-day Matildas as possible.

Except for one critical factor.

Back then, just like today, Australia’s best footballers did not back down.

They took on the world and for a brief moment, inspired by one moment of under-celebrated wizardry, they shocked the world.

*****

In 1988, FIFA was half-pregnant about the idea of having a World Cup for women.

The blokes had one. Since 1930! Diego Maradona had just destroyed all-comers at Mexico ’86, and Italia ’90 was on the horizon. A grand event getting grander.

But female players didn’t have a World Cup.

No one at football’s governing body would commit. Numerous unofficial invitational tournaments were staged through the 70s and 80s, backed by commercial interests instead of anything official.

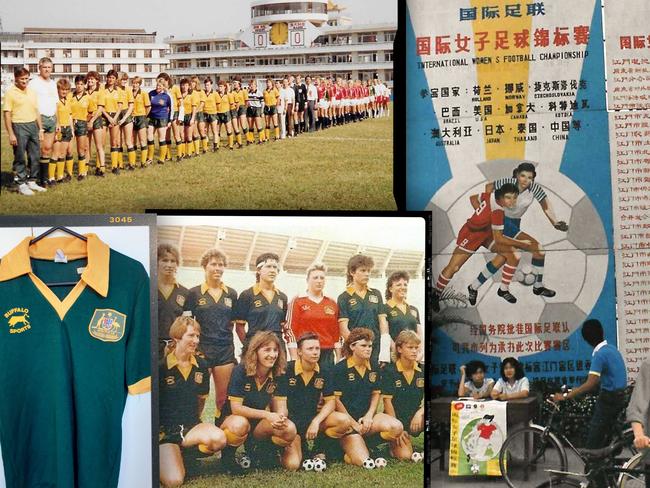

Not until 1988 did FIFA truly wake up, staging a 12-team “Women’s Invitation Tournament”, otherwise known as the ‘pilot’ World Cup.

Somewhat controversially, Oceania’s representative was Australia and not New Zealand, who were then regarded as a better side.

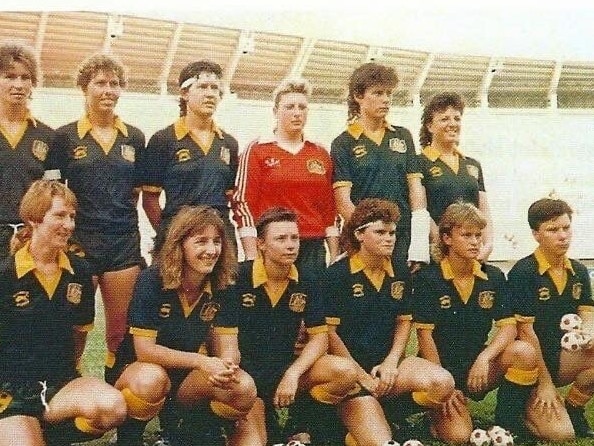

The Australians were a group of part-timers, scratching and saving for every cent to be able to afford to play for the national side, which had its first ‘official’ match in 1979 but had been fighting for recognition long before.

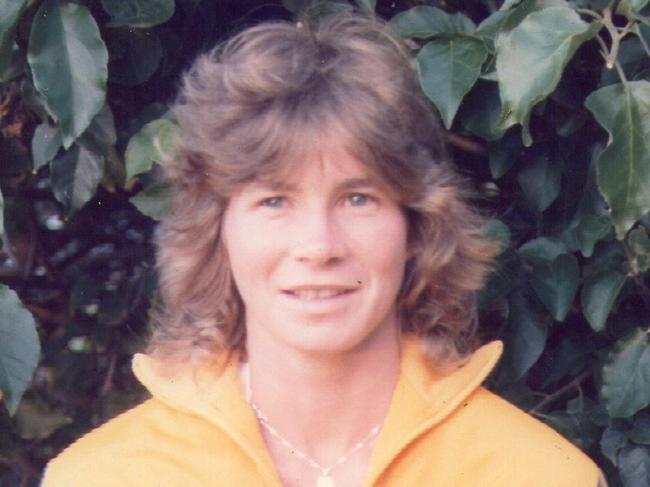

Julie Dolan, captain in 1988 and architect of fundraisers like lamington drives and casino nights, sums it up as such: “A lot of the game was survival. On and off the pitch!”

Most of the ’88 squad were in the workforce, taking holidays or leave without pay to play football.

Talent was emerging quickly. Julie Murray, who would go on to become one of the Matildas’ greatest, was a Canberra student in 1988, but high school, she felt, was overrated.

“I had to write letters to the principal to get time off,” Murray explains. “But I didn’t tell anyone I was going away for football.

“It was just, ‘Wow this is what I want to do, travel and play with the best players in Australia’.”

Murray would go on to play in two World Cups and the 2000 Olympics. But for the first real overseas experience, she and the rest of the Australian team had to sacrifice financially as well.

Each player had to pay $850 to cover costs, which included a week-long camp in Sydney.

It was there coach John Doyle told the media something special was brewing.

“These girls are concerned with excellence,” Doyle said, “and they will kill themselves to get there.”

*****

Getting to the first game against Brazil, which would double as the ‘pilot’ World Cup opener, was an experience in itself.

A flight to Hong Kong then a short, perilous trip on a shaky plane with propellers to the Chinese mainland.

“The thing didn’t balance up the whole way!” recalls Deb Nichols. “And we got off the plane, blokes standing there with machine guns.”

By 1988, Nichols had been around the block a few times.

She grew up in the UK, but football was banned for girls over 12 so was forced to play netball. “Still hate it to this day,” Nichols says.

When her parents immigrated to Australia, Nichols found football again through friends at the migrant hostel they stayed at for six months.

Nichols then went on to represent Victoria for a decade and thought higher honours were beyond her until the 1988 national championships, when she was selected to make her national team debut.

“You’re just so excited to go away, you don’t realise how important that moment is.”

The first game was against Brazil, in Jiangmen’s sapping summer humidity.

Western toilets had been hastily arranged for the dressing rooms, to replace the regular holes in the ground. The pitch had long grass, covered in locusts, but the crowd of over 20,000 counterbalanced the conditions.

“It was like, ‘Wow there are people paying to watch us!’” Nichols says. “This was in an era where you were lucky two men and a dog came to watch you.”

Up front, Australia had a real weapon in the pace of Janine Riddington, who was also a state champion sprinter.

Riddington, like the rest, had to rely on goodwill to get to China.

“I’d just left school to work in a bank but dad got a little bit of sponsorship money from the Narrabeen RSL,” Riddington recalls, unaware of where the rest of the $850 needed came from.

Once in China, Riddington grew wise to the differences between Australia and the rest.

“We borrowed our strip off the Australian under 15s boys side,” Riddington says.

“Your number was defined by what shirt fit you. You’d feel really amateur when treated like that.

“We saw the Norweigians in the hotel, all dressed the same, big slogan on the shirt. ‘No guts, no glory’.

“Just one look at that and you think holy crap, we’re not going to intimidate anybody!”

And @FIFAcom held a global women's tournament in 1988, which #Matildas played in. Lots of latecomers but the important thing now is that all stakeholders bring what's needed to make #womensfootball a real party 🎉⚽ï¸ðŸ‰ pic.twitter.com/NCgxoqsNIb

— moya dodd (@moyadodd) April 1, 2019

But they had an ingredient all great teams have, and the poor ones don’t.

Togetherness; a trait so apparent in the modern-day Matildas, was on full display on that stinking hot day against Brazil.

The South Americans attacked in wave after wave.

Australia barely had a chance, until Riddington was released into open pastures, one-on-one with the keeper, sprinting at full tilt.

It was such a blur, Riddington forgot coach Doyle’s clear instructions.

“He pulled me aside before the game and said if in a goalscoring area, do not chip the keeper,” Riddington says.

So of course, she chipped the keeper.

The goal is eye-popping to this day. Riddington, sprinting, defying physics with a scoop over the Brazilian’s head and gloves. Australia 1. Brazil 0.

Dolan, who mistakenly gets credited with the goal, vividly recalls Riddington’s work of art.

“She’s at full pace! That remains one of the greatest goals I’ve seen,” Dolan says.

Australia held on to record a momentous victory, after which they defeated Thailand to remarkably qualify for the quarter-finals, only to get demolished 7-0 by hosts China.

“We got smashed. Smashed!” Dolan recalls with a smile.

“That was pretty ugly. But the whole experience had life-changing moments for a number of players.”

*****

The whole thing was over in a week for the Australian players, who got straight back to normal life.

“I came home on the weekend, back at school on Monday,” Murray says.

“From training and playing with the national team to doing maths again!”

Goal-scorer Riddington recalls a squabble with team management, who wanted the players to return their kits. They all rebelled and hid them. Riddington, to this day, still has her treasured No.15 from the day she beat Brazil.

And no one has ever complained about the $850.

“We all started our mortgages a lot later in life, but you would not change it for the world,” Nichols says.

The tournament itself forced change.

Two weeks after the final, won by the ‘no guts, no glory’ Norwegians, FIFA’s crusty old men finally announced that a proper Women’s World Cup would be held in China in 1991.

Ever since, the event has grown steadily to the mammoth proportions of the 2023 edition, with packed out stadiums and a TV audience well north of a billion people.

“It’s insane to think, 35 years on, women’s football has made some significant uplifts right across the world,” Murray says. “It’s not just about football, but providing opportunity for women in all areas.”

And the Women’s World Cup has become something else: 32 teams, all in five-star hotels, training venues, games in pristine stadiums.

The final in front of 80,000.

And no one will be playing in a borrowed kit.

More Coverage

Originally published as Hand-me-downs and heart: How the Matildas broke down barriers, upset Brazil at 1988 ‘pilot’ World Cup