Ricky Ponting opens up on his childhood and the best and worst moments of his illustrious career

Ricky Ponting achieved remarkable success but there is one series that stands out as the darkest stage of his glittering career. And another away tour years later was one of his fondest memories. Read the full Q&A with Hamish McLachlan.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ricky Ponting is one of the greatest cricketers to have ever played the game. One of the most superb batsmen, and successful captains of any country, in any era.

Ricky grew up in Tasmania and made the most of the talent he was blessed with.

In part one of a two part interview, we spoke about working hard, his football talent, almost losing his son, the Ponting Foundation, the pressure of leading the country, sandpapergate and retirement.

HAMISH McLACHLAN: How would you rank yourself as a Principal at the Ponting Home Schooling Education facility there in Brighton?

RICKY PONTING: (laughs) On a scale of one to ten, I’m less than one! The patience that teachers have is extraordinary! I’ve got a very good appreciation of what they go through now!

HM: I look forward to reading the term reports.

RP: They’ll be complimentary of the two girls, but the young bloke’s got a fair bit of work to do.

HM: “Too easily distracted with a sole focus on sports”.

RP: Bang on. I set him up in the study in front of the computer, and both our sets of golf clubs are there. Within five minutes he went into his bag, got his putter out and was putting balls on the carpet.

HM: Apple doesn’t fall far from the tree! You’re a product of a very hardworking family. Your dad worked in the mines and on the railway lines, your mum was a curtain maker. What did they instil in you?

RP: Hard work. Dad’s message to me growing up was, “Son, you’re only ever going to get out of anything what you’re willing to put in”. I heard that saying a million times in my early days, whether that be in school or sport. I played most sports as a kid — soccer, footy, cricket as well as some golf throughout the school holidays. I wasn’t allowed to play basketball. Dad’s message was all about not letting opportunities slip.

Watch every ball of the England v Pakistan Test Series Live & On-Demand on Kayo. New to Kayo? Get your free trial now & start streaming instantly >

HM: Had he?

RP: Dad was a very gifted sportsman, but he wasn’t willing to make the sacrifices and do the hard work to be very good at anything he played. He was a scratch golfer at 15, played top level footy in Tassie, and played A-grade cricket with the Mowbray Cricket Club, but for Dad it was all about being with his mates and having a beer at the end of the day. When I was old enough to start showing a bit of sporting talent, Dad was very keen to ensure I didn’t waste opportunities like he may have. It wasn’t like he was pushing me, although his words sometimes could be a little bit harsh.

HM: Like?

RP: I remember one of the first games of club football that I played, U/13’s with North Launceston. I must have had 50 kicks and kicked five goals. I got in the car to drive home, and he said, “Why didn’t you kick six goals today?”

HM: Tough! You lived in housing commission homes at times, and I’ve heard you say it wasn’t wise to be outside after dark too often where you grew up.

RP: We lived in housing commissions when I was 12 through to when I started playing cricket for Australia. We started in a family home in Prospect, lived there for a few years, and then we moved in with my grandparents, Dad’s mum and dad. They had a house in another suburb called Newnham, they had a caravan in the backyard that they would sleep in. We shared the one house. After that we moved into a pretty rough suburb in the northern suburbs of Tasmania called Rocherlea, which was the housing commission area that we lived in. There was some pretty ordinary stuff going on around us, but we didn’t know any better. You could see burnt cars in front yards around you, and you knew it was a bit different than where we might have been previously.

HM: You were clearly a talented sportsman — was there an opportunity at any point to turn left to football instead of right to cricket?

RP: I absolutely loved footy, and I was reasonably good at it. I got myself into state squads and things, and if Dad reads this, he’ll be disappointed that I’m telling you this story, but we used to have the interstate carnivals, and I was captain of the Northern U/16 team. We went to Hobart, played in the carnival, and I was picked in the State Squad. We stayed down there for a State camp, and we had a guy called Ricky Hanlon, who was a legend of Tasmanian football, coaching us. I remember packing my bag to go down, and as I was getting in the car, Dad said to me, “Whatever you do, make sure you don’t get yourself picked in the state team!” He didn’t want me to play footy — he wanted me to play cricket. He knew that I was going to be a better cricketer than I would have been footballer.

HM: How old were you when Tasmania had to change the junior cricket rules around you?

RP: As a nine-year-old I played the whole first season of school cricket without getting out, and then at the start of the next year, they changed the rules so that you had to retire at 30. They were 30 over games, so from then on, I’d open the batting, try and face as many balls as I could, and not score many runs. I’d get a single on the last ball every over, so I retained the strike. I’d bat, and bat, and bat as long as I could. I’d get to the other end and ask the umpire what I was on. I’d try to get to 29 and hit a four or six off the last ball so I could make as many runs as I possibly could.

HM: As an 11-year-old, you played in the U/13 Carnival. 50 over games, five days in a row, and you made four hundreds as an 11-year-old. The next week, you played as an 11-year-old in the U/16’s and made two hundreds. Is that right?

RP: I didn’t get a hundred in the first game of the U/13’s week but made a hundred in the last four. An 11-year-old playing in the 13’s was one thing, but an 11-year-old playing in U/16s was noticed by everyone. You’re pretty much playing against men then at that point! That’s when everything took off, and the first time that I understood that people might have been looking at me or talking about me. I got my first bat sponsorship with Kookaburra on the back of that, so that was when everything started to change.

HM: You left school in year 10, then a scholarship to go to the Cricket Academy in Adelaide the following April?

RP: Yeah — when I left home, I had a pair of runners, a pair of track pants and a couple of T-shirts. I’m not sure I owned a pair of jeans or a collared shirt back then. It was just about packing up what I had in my cricket bag and getting myself over to Adelaide to live with another 15 or so blokes that were four, five or six years older than me.

HM: Was Warnie one of those?

RP: Warnie came over to do some training with us, as he’d just been picked on his first tour for Australia to Sri Lanka. He came over for a month to live and train with us to get himself fit and do some bowling before he left. That was when I first met him. We hit it off quite quickly.

HM: Was he the one who nicknamed you “Punter?”

RP: He was. The story behind that is when I first went to the academy, we were getting paid $40 a month as an allowance. Everything was put on for us food and accommodation wise, so I tried to find ways to turn that $40 into a little bit more. I’d go down to the local pub TAB on a Monday night, Tuesday afternoon or Thursday night when the Tassie dogs were on and try and back a few winners and put a bit more money in my bank account.

HM: Was there a contract you saw of Warnie’s sitting on the front seat of his car at some point?

RP: Ha, I did. He had his Cricket Australia contract sent to Adelaide when he was there, and I got into his car. He had this flash Nissan Pulsar that he’d brought over with him to Adelaide, and when I got in the front seat the contract was sitting there. It was open onto the page that showed how much his contract was. It was an eye opener for me as I had nothing and couldn’t fathom what a contract would look or feel like! I was on $40 a month, and I’d left home with nothing, I didn’t even have a bank account, and every cent was like gold to me. I was hanging out with a bloke who was about to play for Australia on what seemed like the biggest contract in world sport!

HM: It set your focus. State cricket wasn’t far off as a 17-year-old. How’d you go day one?

RP: It didn’t really go to plan. Day one of my Sheffield Shield career was an away game against South Australia in Adelaide. I was rooming with my best mate who I played all of my junior cricket with, Michael Di Venuto, who played the last game of the season before with Tassie.

HM: A one game veteran!

RP: Precisely. We thought we’d nail our preparation, stayed in, got room service and watched a movie. It was my responsibility to set the alarm, but back then we didn’t have mobile phones or anything like that, so I set the alarm on the clock between the two single beds we were sharing. I set the alarm, and off we went to sleep. I woke up to what I thought was the alarm going off in the morning, but it was the room phone. I picked up the phone, and it was the coach, Greg Shipperd, on the other end. “Where the bloody hell are you?” I looked down at the clock, and it was 9.00am. We jumped out of bed, threw our training gear on, grabbed our cricket bag, ran down to the car and drove to Adelaide Oval. The boys were sitting down in a circle waiting for us to get there, and Boony (David Boon) told all of them to not look or talk to at us and make us feel as uncomfortable as they possibly could. It was a frosty start to my Sheffield Shield career, but luckily as the game went on, I got a chance to bat with Boony. We had a good partnership and put on well over 100.

HM: The other thing was you’d pipped him as the youngest ever to play for Tassie.

RP: I had no idea back then, but it was just an amazing day. Coming from Launceston, I idolised Boony, so feeling like I’d let him down day one of my Test career wasn’t ideal.

HM: You progressed quickly to the Australian XI. Who was there when you walked out the first time to bat against Sri Lanka?

RP: Gee … that’s a good question — I actually don’t know. Stuart Law and I were picked to debut in the same Test match, because Steve Waugh was out injured. It was against Sri Lanka in Perth. Tassie had played Sri Lanka in a First-Class game the week before the Test in Launceston, and I’d made a big hundred. I was batting, and I looked up and saw Mum sitting in the grandstand …

HM: … which was unusual!

RP: Very, as the family joke was that Mum was a bit of a jinx on me, so we would laugh about her coming to the games to watch. I got through to the tea break not out, walked off the ground and Mum actually opened the gate for me to come off. She put her arms around me and said, “You’ve just been picked to play your first Test match”. That’s how I found out.

HM: What a moment. You didn’t let her come to many of your matches, did you?

RP: Mum and Dad would have gone to every Hobart Test match, but they travelled very rarely as they have always been most content staying at home. They went for my first Test in Perth, they came over for my 100th Test at the SCG, and one Boxing Day Test match, but if you counted them up, it’d only be six or eight Test matches in total.

HM: Of 168 Tests?

RP: Yep.

HM: In 1996, at just 20, you debuted for Australia — you wore the baggy green all innings but were given out LBW controversially by umpire Khizar Hayat on 96.

RP: I must admit, that’s the closest I’ve ever been to crying on a cricket ground! When I walked off the ground I just thought, “There goes the greatest opportunity to score a hundred on debut”. It was an awful decision. I don’t think I ever played another game that he umpired in — that might have been his last Test match!

HM: It was a dreadful decision.

RP: I definitely would have reviewed that if reviews could be used back then.

HM: In terms of when you felt like you belonged and were of real value as a cricketer to the country, it wasn’t until they moved you to bat at first drop?

RP: Exactly. I felt like a bit of a passenger batting at No.6 in the team. I didn’t feel valued. I was in a really good team as well with two Waugh’s, Boony, Taylor and Slats all ahead of me, but I didn’t handle it very well. I like watching the game really closely, and when you start your batting innings and you’re sitting around for three, four, five hours waiting for your chance to bat, when you go to bat, you’re really mentally drained. It was a hard thing for me to adjust to. There’s no doubt that getting the opportunity to move to No.3 changed a lot of things in my life, and then taking over as captain raised my game to another level. At No.6 I just felt like I was the weakest part of the team, the lowest listed batter.

HM: Did you tell anyone that?

RP: I remember having a conversation in a bar in Hobart with Mark Taylor after a Test match down there. “Mate, just give me a crack at 3”. He just said, “Score some runs down there, and one day you’ll get a chance”. It was Steve Waugh that gave me that chance.

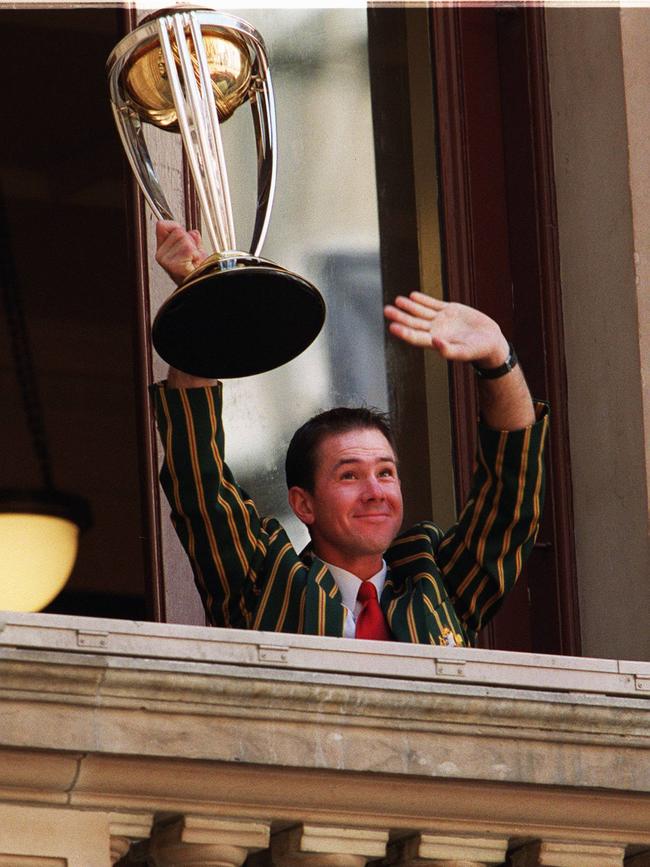

HM: And you nailed it. Of all the moments in cricket, 13,000 plus runs, average of 51.8, three world cup wins, two as captain, twin tonnes in your 100th Test … if I said to you, I can take you back to one moment, and you could experience that feeling again, where do you end up?

RP: My first Test hundred was a really special moment. It wasn’t the best that I ever made, but to realise that you actually can do it, and you are good enough, is a hell of a feeling. That was an Ashes hundred against England in Headingley. The ‘99 World Cup was an amazing tournament as well, as we were down and out. Three or four games into the tournament, we had to win every game to keep progressing to the next stage. We get to the final and play a flawless game against Pakistan at Lords. That was ultra-special. 2003, my first World Cup as captain, having been a relatively young captain going in was great. The two points of difference going into that World Cup were we probably had the No.1 ranked fast bowler in the world in Jason Gillespie, and we had the best spinner of all time in Warnie. Warnie gets ruled out before the first game, and Gillespie after the first game! That just brought that group of players closer together, and really galvanised the team. We got 360 against India in the final, and I remember when we took that last wicket that day, I sprinted around the outfield and did a soccer slide across it. That was an amazing feeling.

READ PART TWO OF RICKY PONTING’S INTERVIEW WHERE HE SPEAKS ABOUT LIFE AFTER CRICKET, INCLUDING REVEALING THE HARROWING MOMENT THAT CHANGED HIS LIFE, HERE.

HM: I sense there is a ‘but’ …

RP: … but I won’t ever forget the Test series against South Africa over there in 2009, after all the big boys had retired. JL, Marto, Gilly, Haydos, Warnie and Pidge. I had guys like Phil Hughes, Marcus North, Ben Hilfenhaus, Peter Siddle was new on the scene, Mitch Johnson, Brad Haddin, Andrew McDonald — it was a really young group of players. South Africa were the No.1 team in the world, and we were going there with after being beaten in Australia. I remember getting to Johannesburg for the first of three Test matches. I went out to the wicket to toss the coin on day one, and I look down, and it’s an absolute green top. It’s green, moist, and I have to bat. I have to send these young blokes out against a really good attack. It was Hughesy’s debut, and I think he got a second ball duck. I’m out there in the second or third over, the balls going all over the place. I managed to hang around for 80 odd, I think Michael Clarke made a hundred, and we went on to win that game. We go to Durban, beat them in Durban, and I remember I deliberately walked 30 metres ahead of the rest of the group when we were walking off the field. I stood near the boundary line and looked back at this group of young blokes on their first tour for Australia. That moment there is one that I’ll never forget. What it meant to a group of young blokes to represent their country, and to do something so special and unexpected. I’d done it 130 times by then, but to see them enjoy it was one of the more special moments I had in my career.

HM: People say the Prime Minister and the Australian cricket captain are the two most scrutinised jobs in the country. Do you feel that you’ve got eyes on you at every decision?

RP: Absolutely, and there’s no hiding that. It takes a while but you can’t let that consume you, you just can’t be thinking what other people might think of a decision you make, or don’t make. You have to stand up, own the job, and own the decisions you make. When you get to become captain, you’ve got a good understanding of the people around you, and what the game needs. Yes, we will get some wrong every now and then, but you make a hell of a lot of decisions before a game even starts! Selection, what are you going to do at the toss, and then once the game starts, you’re thinking about bowling changes, field placements and batting orders. You’re making a lot of decisions. Once the game starts, the coach isn’t doing it — it’s the captain. That’s where it’s a really unique position as a cricket captain, because when the game starts, you are the coach. But, in any big senior role for any business or organisation, every decision you make is scrutinised.

HM: They’re scrutinised, but they’re not publicly scrutinised like the Australian cricket captain, because of the love for the game. Everyone feels like they’re a part of your team.

RP: That’s the way you want it to be. If you wind back the clock a few years, a lot of Australians didn’t want to be a part of it.

HM: Where were you when sandpaper-gate blew up?

RP: Rianna and I had dinner with Danny and Nina O’Brien that night. I got home, and Danny texted me saying, “Have you seen what’s going on?” I had no idea. I just didn’t want to believe it. I’ve never spoken to Smithy (Steve Smith), Davey (Warner) or to (Cam) Bancroft about it. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t force myself to watch Smithy’s press conference when he got back, and I couldn’t watch Davey’s either. I saw a glimpse of Smithy and Bancroft facing the media after it happened at the end of the day’s play. Every single person in Australia wanted to know my views and opinions on it, but I just kept away from it and still haven’t asked about it. I remember walking down Bay Street to get a coffee, and an old lady stopped me in the street and said, “What on earth is going on with your cricket team?” I said, “I haven’t played for five or six years, it’s not my team any more”. It was a shocking time in Australia’s cricket history.

HM: A good reminder around taking years to build a reputation, and seconds to lose it.

RP: Absolutely. You can be as good as you like for five or 10 years, not have an indiscretion anywhere, and then one thing will happen and all of a sudden, everything you had worked for and built up all your life, is gone. With the sandpaper scenario, all of a sudden, we were all back to the “ugly, arrogant Aussies”. What Painey (Tim Paine) and Justin (Langer) have done since has been remarkable.

HM: Tim Paine had played 13 Tests when he was asked to captain the country in the most difficult of circumstances. He has been phenomenal on field, and more so, off it. He has led the team to and helped win back some affection from the cricket watching public.

RP: There’s no doubt about that. You can’t comprehend how difficult that would have been for him. He was holding on by the skin of his teeth just to get himself in the team, then he had to lead it. If you think about the way he was playing, and batting before that South African series, it was just only just good enough to stay in the team. When Smith and Warner aren’t there, you looked around and thought “Who’s going to be captain?” The only person you could have made captain was Painey. He has taken to it, but he had to change himself.

HM: Not always a natural leader like he appears to be now?

RP: If you asked him about that, the early days he had in leadership roles with the Hurricanes, or as captain of an Australia A team to England one year, he wasn’t very good at it. He was the young kid in a hurry, and he had really high expectations of everyone else in his team. He couldn’t understand why they couldn’t do certain things or execute things properly. He was very harsh on them. He had to change his on field and off field leadership, even his persona. Since being named the Test Captain, hasn’t put a foot wrong publicly. Any time he’s fronted the media or fronted the public, he’s always well dressed, perfectly groomed, he speaks really well, and he’s thoughtful with his answers. He’s done a remarkable job, and under the most stressful and difficult of times.

HM: What about the lowest point for you in your career?

RP: Losing the Ashes as Captain in 2005 — by a street, no doubt. We went there with a champion team, and there was a bit of talk around some of the English team being a little bit past their best But we were coming up against a team that were ready for us. Michael Vaughan has said in the last few years how he told the English that they had to play like Australia did. They couldn’t keep playing like England — they had to fight fire with fire. And they did.

HM: It was one of the best Series that’s ever been played.

RP: Agreed. On the first morning at Lords I got hit and split open my cheek, Matty Hayden got hit early on in the head as well, and Justin was hit on the elbow in the first or second over. After I got hit blood was trickling down my cheek, and not one of the English left their position in the slips, the keeper didn’t move, and the bowler turned his back and walked back to his mark, which is what I wanted and what I expected. You just knew then that they were up for it and were going to play a different style of cricket.

HM: You said to me you would do things differently if you had your time again.

RP: I would, I learnt a lot. We were trying to make our training sessions as time efficient as possible for the players. Some guys might want to go down early and get their batting done before the main group comes down, so we weren’t all at the ground for four or five hours at a time doing all our training together. It was all done with the right intentions to make life better, but we just got away from the old-fashioned go into the nets, face the bowlers, and get all your hard work done together. We went away from that a little bit, and by the time we tried to rectify the changes, we were three matches into the Test series and the Ashes had slipped away. Some really good lessons were learnt for me as a captain on that tour, and certainly some of the senior players who thought they had really good control of what they were doing with their preparation. That awoke the sleeping giant in Australian cricket — we got a little bit lazy, and let other teams catch up to us, and it made us hungry and we got better as a result.

HM: I was reading an article written by a journo who spent a year with Tom Brady about six years ago. He interviewed his father as a part of it all, and he said, “It will end badly with Tom and the Patriots, no matter how many more Super Bowls they win”. “Why?” he asked. “Because Tom, no matter what happens, will think he should be the quarterback for the Patriots. He might be 75 and on crutches, but he’ll still think he should be starting”. When did you start to think about retirement? For an alpha male that’s full of competitive juices, I assume it’s the one thing you never want to contemplate.

RP: That’s exactly what happened with me. Looking back now I’ve finished and had a chance to let the dust settle, I know that I played a couple of years longer than I should’ve. When I stood down from the captaincy, which was after the 2011 World Cup, we had those younger blokes around then. Warner was trying to find his feet, Smith had just come into the side, and I was just a bit worried that, if I left then, there wasn’t much leadership in the group. I played on to try and help those guys through, knowing that I wasn’t at my absolute best. I wasn’t allowing myself to play the way I wanted to play, and I was so keen on trying to set the right example and trying to do the right thing that I wasn’t playing with any freedom. My Test average went from over 60 after 100 Test matches, down to under 52 as a result. That’s a drastic drop off.

HM: Was there a particular moment you finally knew you were done?

RP: I don’t ever remember waking up, looking in the mirror and thinking, it’s time to go. I’d wake up every day and think, if I want to have a great game, or get better, this is what I have to do. Even in the last season, in between the Test matches, I’d go back to a state game and make a hundred in no time and do it easily. I ended up being the leading run scorer in shield cricket that last year that I played. I never contemplated retirement until I sat down at dinner with Rianna in Adelaide. I’d got out in the second innings of that game. We sat down for a steak and a glass of red wine, and I said to her “I think that time’s coming”.

HM: What did Rianna say?

RP: Her reaction was a bit different than my Dad’s. It had been a tough time for us, because I wasn’t playing well, and the media was saying it was time for me to go. When that’s happening to you, your partner gets dragged into it as well. She said, “You don’t have to keep doing this any more but I will support you with whatever decision you make.”. I got to Perth, rang my Dad and said, “Dad, it’s time mate. I’m going to retire”. He said, “No you’re not. Don’t be bloody stupid, just go and get a hundred in this game and everything will be fine”. But I knew it was time, and it was.

HM: And just like that, you were a former Australian player.

RP: It ends quickly, and you’re retired a long time, but what a privilege it was to play the game I love for the country I love.

READ PART TWO OF RICKY PONTING’S INTERVIEW WHERE HE SPEAKS ABOUT LIFE AFTER CRICKET, INCLUDING REVEALING THE HARROWING MOMENT THAT CHANGED HIS LIFE, HERE.

MORE NEWS:

Marcus Stoinis gives up six-figure deal in Caribbean Premier League due to coronavirus concerns

Originally published as Ricky Ponting opens up on his childhood and the best and worst moments of his illustrious career