Geelong legend Michael Turner opens up on his Pancreatic cancer battle

In January, Michael Turner was told he might only have six to 12 months to live. Now, the Geelong legend is about to head back into the surf. He opens up on the fight of his life.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Some time over the next week, Michael Turner will feel the rush of his first surf in one year.

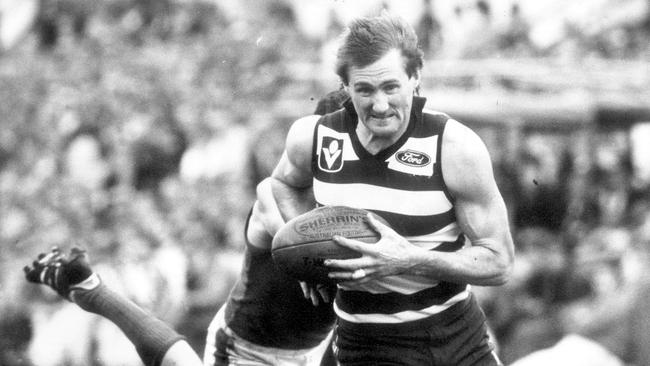

Throughout his life in football, the Geelong Team of the Century wingman and 25-year boss of the Geelong Falcons would go for a dip every week.

But this next wave will be no ordinary ride.

Over the past 11 months, Turner has been locked in the fight of his life, and at times, was barely able to leave his couch.

Only two weeks after losing his mother in January this year, Turner was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and was told he may only have six to 12 months to live unless he could climb a medical mountain.

Straight to the point as always, the man who thrilled crowds in the 1970s and ’80s, wore the Victorian jumper 12 times, and helped launch hundreds of AFL careers including those of Luke Hodge, Patrick Dangerfield, Jimmy Bartel and Travis Boak, asked the doctors what his chances of survival were.

They said about 15 per cent, unless he could do five things.

That included a nine-hour surgery to re-wire his insides as part of one of the most serious and complex procedures there is outside of a transplant, and endure 12 rounds of maximum dose chemotherapy.

At the worst of it, Turner, 69, could barely move, had trouble eating, and asked his oncologist for a month-long break from the treatment because he was so ill.

The former exhilarating goal kicker and Geelong captain lost 16kg this year; his powerful and athletic frame reduced to skin and bone.

Not only did Turner contemplate his own funeral in the winter months, he picked out the songs and prepared the PowerPoint presentation.

“I have always been pretty organised,” Turner said, laughing, as he overlooked the Lorne front beach and sipped a purple-coloured fruit smoothie.

“I have never feared death. That shocks some people.

“But what I fear is, and what I lost during that 10 months, is my quality of life.

“I’m gradually getting that back now, but the only thing I haven’t got back is the surfing, but that will happen soon.

“Pancreatic cancer is the worst one you can get. It (pancreas) sits next to your liver and if it hits your liver you are gone.

“I’m realistic about it all. There is a fair chance it will come back and if it does then so be it.

“I can’t go through the operation and the chemo again. If it did come back it would just be radiotherapy.

“But sitting here talking to you now I feel really good. I’m exercising and putting on weight again.

“I was able to travel to New Zealand to see my son and his partner, and I have been lucky to have incredible support from my family and my specialists.

“It’s been very challenging, but I’m one of the lucky ones.”

Turner’s life changed in January on a trip to the toilet.

“I was doing a wee and it (urine) looked like Coca-Cola, so I said to my wife, ‘Come take a look at this’,” Turner said.

“She said, ‘That doesn’t look good’, and she took a look at my eyes and they were yellow, and soon my skin was yellow.”

He called a mate at the hospital who said he needed to hurry in. It was jaundice.

Although it gave him horribly itchy skin, which he scratched off in some parts on his arms it was that bad; the jaundice was an early alert to a much bigger problem.

The tests indicated he had pancreatic cancer, and required a nine-hour operation called the Whipple Procedure.

It is where the surgeons take a look inside at his organs to assess the cancer, and for those who are lucky, remove and rearrange things for a chance at life.

Turner sat on the operating table looking at about 100 giant hooks used to help open him up, and hoped for the best.

Then the surgeons sliced him open from chest to belly button.

“They took out half of my pancreas, my gall bladder, and some of my intestine,” he said.

“Plus, they cut out a couple of my veins, and then they cut a hole in your stomach, re-plumb you back the other way and poke your pancreas into your stomach, so you don’t become diabetic and you can digest your food.”

With seven tubes helping him breathe, Turner opened his eyes and asked his wife, Karen, one question.

“I said, ‘How long was I in for?’ The surgery only takes three hours if it is bad news, and it (cancer) is in your liver because if it is, there is nothing they can do for you,” Turner said.

“They just sew you back up.

“But Karen said I was under for nine hours. I said, ‘Good, I’m a chance, then’.”

The surgery was as successful as the doctors could hope.

But only a few days later, the family suffered another life-threatening blow, as Karen was seriously injured in a nasty and unusual car accident.

Karen had driven her son, Che, to the airport about 5am so he could resume work as a builder in New Zealand following his father’s major surgery.

Upon her return to the accommodation close to the Box Hill Hospital, Karen saw a man lurking near a dumpster.

A little spooked, she hurriedly got out of her car to open the gate, but as she climbed back into the driver’s seat her foot slipped.

Karen mistakenly hit the accelerator instead of the brake, and the car took off.

The side of the car jammed up against the wall, squeezing Karen in between the car and the car door.

She fell out of the car with horrific injuries including a ruptured lung, a shattered pelvis, and severe cuts and bruises.

In that moment, Karen lay on the ground in the dark, gasping for breath, fighting for her life.

That is when the shifty-looking bloke in the hooded jumper walked over to her.

“Karen could barely breathe, but she said to him, ‘I’m in trouble, can you help me? Can you please call for help?’” Turner said.

“But he looked at her, and I’m not sure if he wanted to rob her or whatever – she was clearly in a bad way.

“But he just walked off.

“He left her for dead.

“I’ve mellowed in my old age. And I know people have problems and mental health and drug issues.

“But at this point she was in a worse way than I was.

“Twenty minutes later two tradies rocked up, because they were going to the gym, and they said they didn’t normally go to the gym at that time.

“But she saw them and that’s when she thought she would OK. Because they were tradies.

“They saw her, rushed over, got stuff out of their car to help her like towels and stuff, and they called an ambulance.

“She was lucky to survive. Those two fellas saved her life.”

Karen also developed deep vein thrombosis and required plastic surgery as part of a months-long recovery.

Che flew back from New Zealand to help look after his mum and dad, along with their other son, Levi, from Barwon Heads.

Turner’s two great footy mates, Brian Taylor and Ricky Barham, tried to sort everything else; the communication with friends, the queries, anything else they needed.

But it got harder for Turner as winter set in.

Pancreatic cancer requires the strongest possible chemotherapy. Turner proved himself to be a tough cookie over 245 games across 15 seasons at Geelong, but the treatment almost broke him.

Every second Monday he would sit in Lorne Community Hospital for five-and-a-half-hours for the chemotherapy to be administered.

Then he took another bottle home to ingest on Tuesday and Wednesday.

When the steroids wore off by Friday, the big low would hit over the weekend, gripping his entire body.

The treatment wreaked havoc with his stomach, he felt horrific, and every movement was difficult.

He would spend the next seven days trying to feel well enough to contemplate having the next dose.

Then the cycle would repeat.

“You would try to get in a cocoon, physically and mentally,” he said.

“You are just trying to stay comfortable, even if it is just lying on the couch all day.

“The chemotherapy is like putting Roundup (weed killer) in your system.

“It makes you super tired, super crook, your digestive system is trying to get it out, going to the toilet is pretty challenging, and your tastebuds go off.

“I would look at something and say, ‘I know that tastes good’, and I would eat it and it would taste horrible.

“But you need it (chemotherapy) to eliminate the cancer cells in your bloodstream, so they don’t go around in your blood and lob on a perfectly good kidney or something and start another tumour.

“But after four doses I couldn’t do it anymore.

“So I said to the oncologist, ‘I need a break’. I said, ‘If the cancer doesn’t kill me the chemotherapy will’.”

So Turner took a month off; enough time to feel well again, before he gritted his teeth and battled his way through the next eight doses.

It tested every ounce of his strength, every inch of his will, but Turner’s friends, colleagues, former teammates and the draftees all say he is a tough bugger.

When Luke Hodge’s career was threatening to go off track before it even began due to some big weekends in Colac, or cricket commitments, Turner didn’t hesitate to give him some blunt feedback.

“He’ll tell you this himself, but I would take him into the property steward’s room and tear strips off him – and this was a different era – but I was pretty direct because you had to be,” he said.

A straight-shooter. Hard but fair. And incredibly popular in footy for decades.

Turner never sidestepped a tough question or conversation if it could benefit a draftee.

Turner told the Hawks they had to draft Hodge at No. 1 over Chris Judd and Luke Ball in 2001, and four premierships probably proved him right.

So, after the full 12 rounds of chemotherapy, Turner’s oncologist congratulated him in her office late this year.

By then, his 80kg frame had reduced to 64kg.

But he had achieved a rare feat.

“She said to me, ‘Congratulations’. I said, ‘What for?” he said.

“She said, ‘I have been doing this for a long time, treating pancreatic cancer, and only one other person has ever completed the full 12 rounds’.

“Everyone else stopped it because it just made them too sick. It makes you so crook, people pull out. They can’t keep going.

“I said is the other person alive? She said he was. So that’s good.”

Before the chemotherapy, the cancer count in Turner’s blood tests was about 700. Normal is 38.

Turner said with a smile his latest test came back at 25.

That is well enough to pull the wetsuit back out for Christmas, even though he still feels colder than normal, especially in his fingers and toes.

But it could be the happiest surf of his life, as he prepares to gather around the tree with his grandchildren for a Christmas he feared he would never see.

“I would never say I am in remission or that I am cancer-free because pancreatic cancer has a bad habit of coming back,” he said.

“Even though you go through all of that your survival rate is 50 per cent. Most normal cancers is 90 per cent survival rate.

“I am realistic about it all.

“But I am getting my life back, getting my lifestyle back. I’m back up to 70kg and I’m incredibly grateful. I have such an amazing family and support team and the doctors and nurses who helped me through everything.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Geelong legend Michael Turner opens up on his Pancreatic cancer battle