The world was stunned by the audacious attack against Pearl Harbor 77 years ago. But not all. The foundations had already been laid. The lessons already learnt. And one man strove to prevent it from happening.

In December 1941, The United States fully expected to be at war with Japan at any time.

In the days and weeks before the Japanese attack, the United States government and military was racing to prepare.

Washington had issued a formal war warning to all its commanders. It expected them to establish an extreme level of alert and preparedness.

That Pearl Harbor wasn't ready was not due to any lack of intelligence. It’s just that its new commander simply could not believe his ships were at risk in their remote, picturesque harbour.

But every indication was that they were.

In fact, the United States Navy had itself practised the concept itself repeatedly in the 1920s.

And Great Britain had already pulled just such a stunt off, only 13 months earlier.

The United States had been in the box seat.

Aboard the Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious was an illegal observer. His name was Lieutenant Commander John N. Opie III, United States Navy. His mere presence aboard a British warship was an outright breach of the neutrality the United States still clung to.

Some in Washington had been determined to learn as much as they could from Britain’s desperate fumbles in what was the first example of a ‘modern’ war.

Unfortunately, not everyone was paying attention.

PEARL OF AN IDEA

Britain was in a desperate position by late 1940. France had fallen and the Italians had thrown their weight behind Germany.

Now the already stretched Royal Navy found itself fighting on two fronts.

Something simply had to be done to take Italy’s battleship force out of the equation.

Just such an idea already existed.

The Royal Navy almost pulled a Pearl Harbor in 1935: The Italians had invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Convinced that retaliation would be ordered, Admiral William Fisher instructed his commanders to find the best way to hurt Mussolini in a pre-emptive strike. The answer: A surprise night air attack on their main fleet harbour at Taranto.

It was the plans drawn up for this cancelled operation that formed the basis of an actual attack in November 1940.

The task fell on just one ship: Britain’s newest aircraft carrier, the heavily armoured HMS Illustrious. At Pearl Harbor, Japan used six.

On November 6, 1940, HMS Illustrious departed Egypt with an escort of battleships, cruisers and destroyers. Their movements were masked by several convoys weaving their way to Malta, Greece and Crete.

On board was Lieutenant Commander Opie, USN.

The British called him an ‘observer’. To everybody else, he was a spy.

Opie oversaw every aspect of the operation. He stood by as admirals and captains thrashed out their plans. He saw the aircraft being prepared in their hangar. He listened in on the briefings for the British pilots.

He duly noted it all down, to be reported in full to his US naval commanders back in Washington.

LESSONS OF TARANTO

On the night of November 11, 1940, HMS Illustrious and a small escort successfully slipped close to the ‘heel’ of Italy without being noticed. Her force of 21 Fairey Swordfish bombers were launched into the darkness.

US military personnel had regarded this biplane with derision: To them it was an anachronism, a relic of a bygone age. “Where did that come from!” Fleet Air Arm legend reports one US officer asking. “Fairey’s,” replied an RN aviator. “That figures,” quipped the US officer.

But the Swordfish, affectionately called a “Stringbag” because of its versatility, could do something US aircraft could not do: engage in aerobatics at virtually zero height — at night.

Established thinking considered a low-level attack on a shallow harbour to be impossible. Torpedoes would plunge deep before their controls brought them up again. But the British had found that keeping the torpedo’s nose high as it fell with a strand of wire caused the weapon to ‘belly-flop’ and not dive.

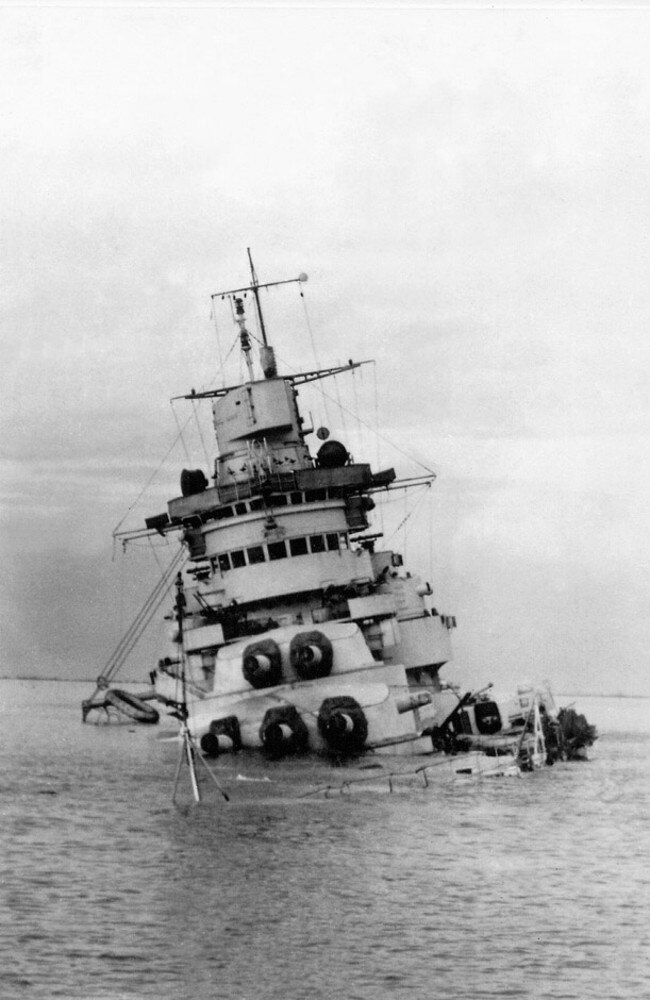

Nor could the night attack on Taranto be called a surprise. Britain had been at war with Italy for many months. And the harbour had already been shooting at shadows earlier that same night. But only two Swordfish aircraft were lost in the attack. And three Italian battleships were heavily damaged or destroyed.

It was a result out of all proportion, and beyond all expectation.

The balance of the war was suddenly toppled back in Britain’s favour.

The world sat up and took notice.

Japan’s top admiral, Isoroku Yamamoto, had already been contemplating a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. But the British success at Taranto proved it could be done.

Yamamoto resolved to learn all he could.

Delegations of Japanese diplomats, engineers and military staff were sent to Italy to interview Italian commanders who had been at the heart of the battle. They also examined the layout of the harbour and the damage to the ships. Most importantly, the Japanese learned from the Italians another technique to keep torpedoes shallow — a collapsible wooden fin.

Nor was the significance of Taranto lost on Lieutenant Commander Opie.

His report was comprehensive, detailing several main points. Among them were:

AT times of high risk, ships were safer at sea instead of harbour.

ANTI-aircraft fire was not as effective as expected.

LOW-flying aircraft caused ships to shoot each other.

He expressed his view to his superiors in Washington that he should travel to Pearl Harbor to discuss its defences.

This never happened.

WAR WARNINGS

President Roosevelt was in a bind. He had been elected on the back of a ‘never war’ campaign. Now he was convinced he needed to do all he could to support Churchill in his struggle against Hitler and Mussolini. And Japan needed to be put back in its place.

But he felt his only option was to set the scene for an ‘incident’ to excuse a formal declaration of war under the US Constitution.

Many senior United States Navy commanders did not want their ships at Hawaii. The Pacific Fleet’s normal home was San Diego, at the heart of the extensive support network it needed.

The Commander of Pearl Harbor at this time, Admiral James Richardson, was one of them.

But President Roosevelt insisted his fleet sit in the middle of the Pacific as a warning to the irate Japanese.

Then, in January 1941, Opie’s report began to circulate. His ‘executive summary’ was widely read. Others began to express fears about the exposed position of the Pacific Fleet.

It had little effect.

In fact, Admiral Richardson was relieved of his command of Pearl Harbor in February for continuing to contradict Roosevelt’s view.

In his place was put the much more politically palatable Admiral Husband Kimmel.

Gradually, the shock of Taranto faded into the background.

DAY OF INFAMY

By December 6, the US knew an attack was imminent. Perhaps against the Philippines. Perhaps against Malaya. Never 5400km miles away, against such a formidable target as Pearl Harbor!

This belief was the root cause of the whole tragedy.

At dawn on December 7, 1941, the Japanese set six aircraft carriers and 355 aircraft against the unsuspecting Hawaiian anchorage.

The outcome was roughly double that of Taranto. Six US battleships were sunk or severely damaged.

Significantly, though, the American aircraft carriers were not there.

It’s an often told story.

Nobody knew for certain Pearl Harbor would be targeted. But plenty had feared it. It was always going to be one of the top contenders.

Most importantly, Washington believed Pearl Harbor and Admiral Kimmel had been given plenty of warning. Ships should have been crewed. Guns should have been manned. Patrols should have been in the skies. Lookouts should have been alert.

They weren’t.

Admiral Kimmel was charged with dereliction of duty, and forced into retirement.

BLAME GAME

Inquiry after inquiry focused on how intelligence could have offered clues to warn of the attack. But Admiral Yamamoto had been careful not to broadcast his intentions.

More rarely addressed was the smothering web of assumptions that made Pearl Harbor possible.

Just as the US military establishment had dismissed the British biplane, it derided Japanese aircraft as being inferior copies of its own. They weren’t.

It rested comfortably in the belief Pearl Harbor was too shallow for torpedo attack. It ignored the fact Taranto was shallower.

“Our carriers can’t strike them, so they can’t strike us” was the mentality of the day. But the Japanese had thought differently.

Ultimately, Japan’s spectacular success on December 7, 1941, was nowhere near enough.

Six months later, the US all but ensured eventual victory when it sank four Japanese carriers off the island of Midway for the loss of just one of its own.

“Remember Pearl Harbor!” was the rallying-cry of the US military during, and after, World War II.

But remember what?

A surprise attack? A string of human errors? Putting politics ahead of pragmatism? Or ignoring inconvenient truths?

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

FBI warning as Israel reveals how it will mark October 7

A chilling message has been issued as Israel prepares to mark the grim anniversary of the attack that changed the world. See the photos, video.