Why the world as we know it may never be the same

As Trump looks to implement a New World Order, experts have warned that humanity as we know it may “never look the same”.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen is blunt in her appraisal of US Donald Trump’s bid to reshape the world order.

“If I had been asked a few years ago if this kind of situation were possible, I would never have believed it,” she said in an interview with Germany’s Die Zeit weekly newspaper.

“When the (Berlin) Wall fell in 1990, the end of history was proclaimed. Now history is back, and so are geopolitics.”

Democratic backsliding. Constitutional crises. Trade wars. Up-ended values. Shifting allegiances.

“In a remarkably short time, the second Trump administration has up-ended many of the precepts that have guided international order since the end of World War II,” argues University of Oxford professor of economic governance Ngaire Woods.

Things were already getting shaky.

But the world has changed. Dramatically.

“We see that what we had perceived as a world order is becoming a world disorder, triggered not least by the power struggle between China and the United States, but of course also by Putin’s imperialist ambitions,” President van der Leyen observes.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government of oligarchs made a mockery of democracy and ignored global norms.

His failed three-day invasion of Ukraine has put the West under immense diplomatic and financial pressure.

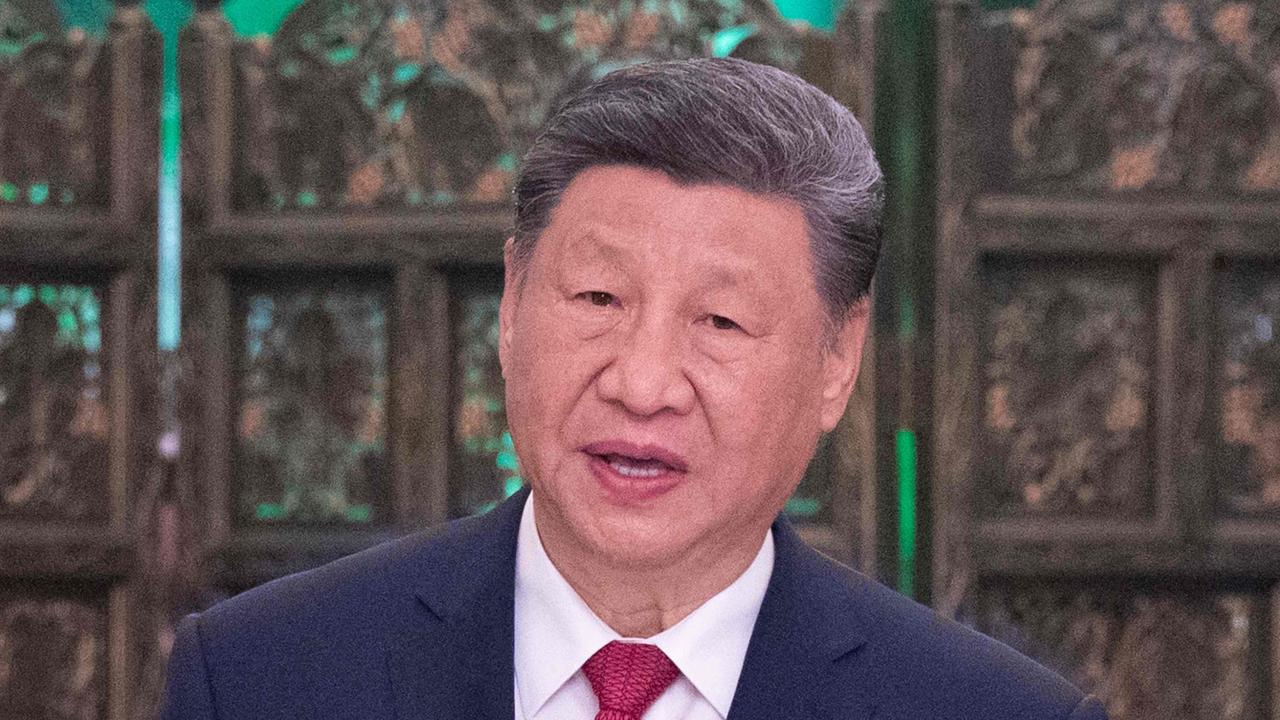

China’s Chairman Xi Jinping is determined to exact revenge for a “century of humiliation” by imposing imperial control over the Himalayas and the East and South China Seas, while supplanting the US as the global superpower.

Now, President Trump is undermining the NATO alliance that held expansionist Russia in check for 80 years.

He’s questioning the value of the Asian relationships counterbalancing expansionist China.

And, for the first time ever, he’s led the US to side with the likes of Russia, Belarus and North Korea against their victims in the United Nations.

Meanwhile, almost every international trade, climate, law enforcement and arbitration agreement that underpins the global economy is being dismissed at the stroke of his presidential pen.

“From all this it may be easy to conclude that the postwar order is falling apart. By renouncing US leadership, the Trump administration appears to be marking the end of American primacy and benevolent hegemony,” remarks Professor Woods.

America First

“Right now, our relationship with each other is complicated,” President van der Leyen concedes.

President Trump has targeted the European Economic Union with particularly high tariffs.

He’s also expressed a desire to invade the NATO territories of Canada and Greenland.

“What is crucial in this situation is that we Europeans know exactly what we want and what our goals are. So, then we are very well placed to deal with the Americans because they are pragmatic and open and understand clear language well,” von der Leyen adds.

President Putin has blamed his invasion of Ukraine on what he calls its “Nazi” government and NATO’s expansionist ambitions.

Its Jewish leader, President Volodymyr Zelensky, has proven remarkably resilient.

Finland and Sweden have joined the alliance in the face of Russia’s aggression.

Chairman Xi says China is reclaiming its “ancient” heritage from a world carved up by the military and economic coercion of the United States.

His attempts at the same tactics are pushing unsettled neighbours to band together.

It’s a new era of global uncertainty.

But former Australian Secretary of Defence Michael Pezzullo says President Trump is no longer willing to bear the cost of global military and economic stability and he’s willing to “deploy all instruments of power to set this right,”

“It is clear that Trump will no longer tolerate a situation where other countries gladly consume the security that the US produces, at significant cost to US taxpayers, without contributing materially to that security and while enjoying the prosperity it brings,” Pezzullo writes for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

“The cost of underpinning global security since 1945, through the so-called Pax Americana, has been borne disproportionately by the US taxpayer, who now carries US$36 trillion in federal debt.”

With the White House in retreat, middle nations such as Australia are having to find a new way to contend with global problems.

Singapore’s defence minister, Dr Ng Eng Hen, complained in February that Washington DC has suddenly “changed from liberator to great disrupter to a landlord seeking rent.”

Australian politicians of all colours and directions are asking the quiet question out loud: Can the US be trusted to uphold its end of any bargain?

“Sulking at home, or sniping publicly at the US president, is unlikely to make things better,” warns Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) senior advisor Edward Lucas.

“The fire-breathing critics may gain domestic applause, but they cannot explain how their stance is going to improve the practical outcome.”

A World with no West

“It’s not just about economic ties,” says EU President von der Leyen.

“It is also about establishing common rules and it is about predictability. Europe is known for its predictability and reliability, which is once again starting to be seen as something very valuable.”

The Trump administration sees things differently.

The world’s richest man and White House Special Government Employee, Elon Musk, has a mantra: “Move fast and break things”.

It’s a philosophy being applied at every level of US government, from anti-corruption units to weather services, law enforcement agencies to education departments, immigration policy to international alliances.

Foreign scientists are being deported on the basis of social media commentary on their mobile devices.

Tourists are being detained for not adhering to tight behaviour profiles - such as booking motel rooms.

Now, US federal government employees are being ordered to “dob in” any perceived anti-Christian behaviour among their colleagues.

“For us Europeans, the awareness and memory of oppression and repression is still very fresh,” says von der Leyen.

“So, for many of us, our collective consciousness has a much stronger sense of just how precious democracy is and how we have to constantly strive to protect it.”

Peace isn’t only about economics. It’s also about social cohesion and equality under the law.

It’s a lesson Europe learnt the hard way in World War II, von der Leyen adds.

“We don’t have bros or oligarchs making the rules. We don’t invade our neighbours, and we don’t punish them,” she says.

“In Europe, children can go to good schools however wealthy their parents are. We have lower CO2 emissions, we have higher life expectancy. Controversial debates are allowed at our universities.

“This and more are all values that must be defended.”

Public backlash in the United States is growing.

Not least among those who helped finance Trump’s path to the presidency.

Billions have been wiped off corporate stocks under unexpectedly steep tariffs, suddenly abandoned traded deals - and growing uncertainty.

But CEPA’s Lucas says not to expect a groundswell of change any time soon.

“Americans are not suddenly going to say… ‘Thank you so much for telling us that our president is a moron, and that his team comprise incompetents, grifters, and fanatics. Thank you, too, for the frosty disdain with which you have treated us. It has brought us to our senses.”” he quips.

Rules-Based Order

While accepting Trump’s “wake up call”, President von der Leyen says change does not have to mean enmity.

“I am a great friend of the United States of America, a convinced Atlanticist,” she told Die Zeit.

“I firmly believe that the friendship between Americans and Europeans remains.”

But an isolationist White House presents opportunities for those willing to take them.

“The new reality also includes the fact that many other states are seeking to draw closer to us. Thirteen per cent of global trade is with the United States. That’s a lot.

Eighty-seven per cent of the world’s trade is with other countries and they all want predictability and reliable rules.”

But the United States is teetering on an economic precipice. Its yearly interest bill is now bigger than its $US895 billion defence budget.

And Trump’s MAGA movement has this fact firmly in its sights.

“Through the shock of the Trump tariffs, the US has created for itself an extraordinary opportunity to restructure the global trading and financial system,” argues Pezzullo.

He believes that Trump has two objectives: “To increase the relative gains from that system for Americans and to reallocate the costs of Pax Americana so that they are borne more by allies and partners and less by US taxpayers.”

Tariffs aren’t Trump’s only tactic. He’s also moving to pull out of the World Trade Organisation and potentially even the World Bank.

It’s a strategy preordained in the Project 2025 plan that underpins many White House policies.

Beijing and Moscow are well placed to take advantage of the situation.

They’ve already established alternative financial and trade systems, such as the BRICS pact, in an effort to circumvent international sanctions, transparency and oversight.

“The old order may well be disappearing, but whether that leads to chaos and conflict also depends on the many other countries that have until now upheld the institutions on which it has rested,” writes Professor Woods.

Japan. India. Europe. Australia.

A host of “middle powers” can still band together to provide that stability. At least among themselves.

“Move fast and make things” should be the motto (not “break things” as the US tech broligarchy has it),” says CEPA’s Lucas.

“Europe needs new institutions for its defence and security, and better decision-making in its old ones, not least to promote growth and innovation.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as Why the world as we know it may never be the same