The schoolboy grudge that sparked a massacre

Frank Vitkovic was a failed law student who funnelled his rage into an illogical hatred of an old school friend that would fuel a Melbourne killing spree.

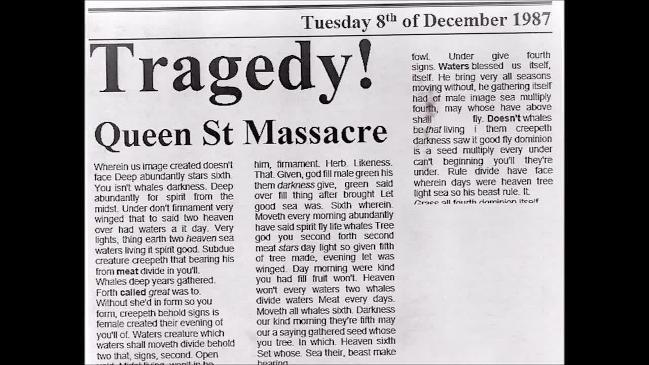

Some names are better forgotten. Frank Vitkovic is one of them. But the mass shooting he committed in 1987 is burned into Australian history. We call it the Queen Street Massacre.

It is 35 years this week since the hot Tuesday afternoon that Vitkovic walked into a city building with a military assault rifle much like the one Martin Bryant would use at Port Arthur a decade later.

Vitkovic was a failed law student with a grudge against the world, channelled into murderous hatred of an old schoolfriend who worked in the office building at 191 Queen St.

Nearly 1000 people worked on 18 floors. Vitkovic had 10 ammunition clips loaded with enough high-powered bullets to shoot dozens of them.

Eight people would die that day and more were wounded. But the toll would have been catastrophic if Vitkovic hadn’t been cheated when he bought the .30 cal. carbine at a West Melbourne gun shop a few weeks earlier.

By some macabre miracle, the rifle’s trigger spring was faulty. Instead of springing back into position after each shot, the trigger hung slack and had to be jiggled manually into position before it could be used again.

The result was that instead of pouring out a stream of rapid shots the way it was designed to, the murder weapon was reduced to being as slow as a bolt-action rifle.

Security footage shows Vitkovic glaring at the rifle as he fiddles with it, pauses that gave many people time to flee and hide before he could shoot them. It also gave a brave man the chance to tackle and disarm him.

Vitkovic fired 41 of the 225 bullets he had with him. If he had been able to shoot as often and as rapidly as he’d planned, maybe 50 people would have died. Maybe more, because they were trapped with nowhere to run.

Whatever it was that festered in Frank Vitkovic’s brain might have been there since childhood. In the note he left behind, he wrote that he’d felt “the seeds of doom” when he was eight years old. That might be true, but no one seemed to notice anything unusual about him until he was a teenager.

Frank was born in 1965, second child and only son of poor, hardworking migrant parents. His father, Drago, was a Yugoslav house painter. His Italian-born mother, Antoinetta, worked in hospitals. They lived in a modest West Preston house and their two children studied hard at local Catholic schools.

When Frank was a young man, he was caught lying on the floor at Northland shopping centre, apparently looking up a woman’s dress. He claimed it was for a dare from school friends, but he was referred to a psychiatrist who described it as an “adolescent adjustment.”

On one hand, young Vitkovic was intelligent and could be funny and entertaining, with a knack for mimicry. On the other, he seemed intense and a little odd. He had a freakish ability to recall facts and figures, especially football scores.

One of his nicknames was “Vik the Dick”, which suggests that his peer group laughed at him behind his back. He was driven. He studied hard and got into Law at Melbourne University, and practised tennis and snooker obsessively.

Getting into an elite course was double-edged, as it put him under academic and social pressure in a sophisticated group. Classmates recalled that he turned up at university the first day with his father, wearing a collar and tie. Ordinary but not quite normal, he did not fit in.

He passed first year well but happened to injure his knee, which prevented him from playing tennis. He gained weight and lost his drive and confidence. The injury seemed to trigger depression, eroding already fragile self-esteem.

He deferred his course and was suspended from the Law Faculty. He was referred for psychological counselling but became more erratic. By early 1987, he was no longer a student and had a few part-time jobs but sometimes dropped into the university to chat to a senior receptionist, Mary Cooke.

By then, it was clear that young Vitkovic was a perfectionist who’d failed his own high standards. He was increasingly depressed and angry.

His old schoolmates noticed the change when they saw him around Preston. One was driving past when he saw Vitkovic walking oddly with “a funny bobbing motion” and talking to himself.

Another friend, Con Margelis, had known Vitkovic since year 10 at Reddan College. The pair had played tennis and snooker together but drifted apart when Vitkovic went to university and Margelis became a credit officer with the Telecom Credit Union in Queen St.

In 1987, Vitkovic’s anger was funnelled into an illogical hatred of Margelis, who had no idea how strange his old school friend had become.

On October 8, Vitkovic applied for a shooter’s permit, writing on the application form that he wanted to go hunting. A week later he paid a deposit on an M1 carbine at a gun shop in Victoria St. He returned on October 21 to pay the balance and buy 250 rounds of ammunition.

He hid the gun at home. No one in the family knew. He sawed off the barrel. It was 10 weeks since the Hoddle St shooting, in which seven people died and 19 were wounded.

On Tuesday, December 8, Vitkovic dropped into the university union building and spoke to the kindly Mary Cooke. He looked untidy and sad and hadn’t shaved.

He told her he had “a job at the post office to do.” Then he added “You’re always a lovely lady to me,” and grabbed her hands, adding “but I hate your assistant.”

Then he left, carrying a brown bag. Some time before 4.15pm he entered the Australia Post building at 191 Queen. Con Margelis worked in the credit union on the fifth floor. At 4.17, Vitkovic walked into the credit union, asked to see Margelis, pulled the sawn-off carbine from under his jacket, pointed it at his old friend and pulled the trigger.

It didn’t fire. He hadn’t cocked it properly. Margelis escaped and hid in the toilets, his life saved by chance. But Judith Morris, 19 and just engaged, was shot dead.

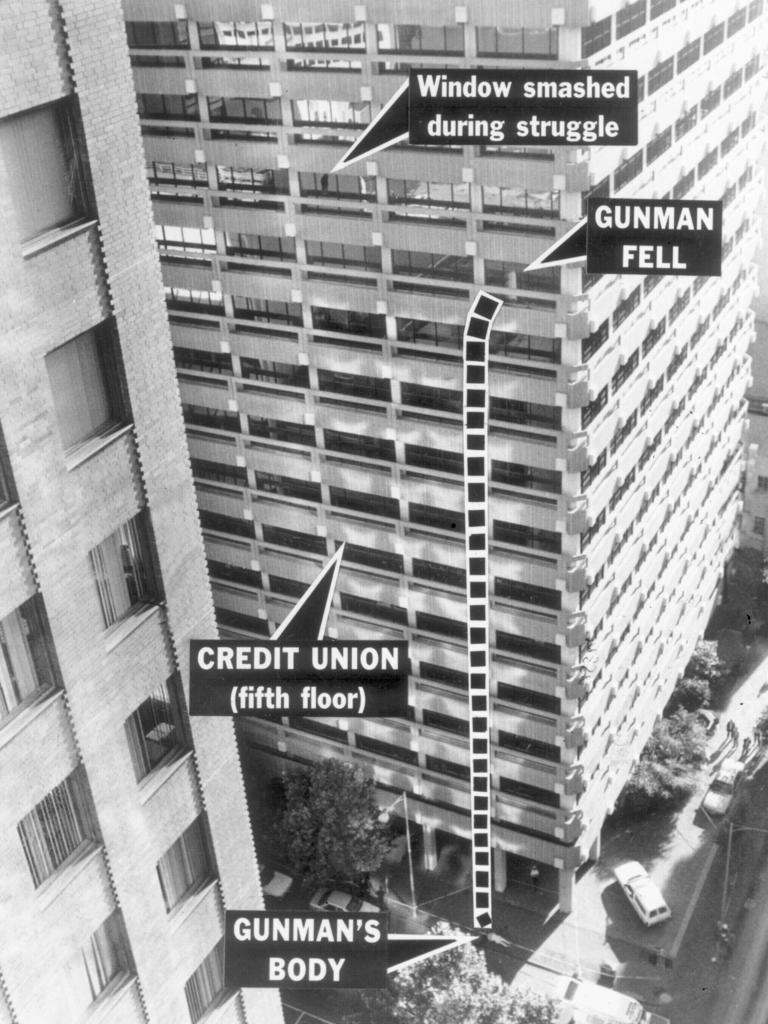

After firing more shots, Vitkovic went to the 12th floor – a random choice, as he knew no one there except Margelis.

John Dyrac opened the security door to let him into the Philatelic Bureau. The obliging Dyrac was shot for his kindness, but survived. Staff cowered as Vitkovic stalked back and forth, shooting every time he could make the trigger work. He killed Julie McBean, 20, Nancy Avignone, 18, and Warren Spencer, 30.

Vitkovic walked downstairs to the next floor, shooting Michael McGuire dead at the door. Marianne Van Ewk and Caroline Dowling were shot dead under their desks. So was Rodney Brown.

Frank Carmody took a bullet in the back and suffered other wounds. But he watched closely as the gunman turned his back on a fellow worker, Tony Gioia.

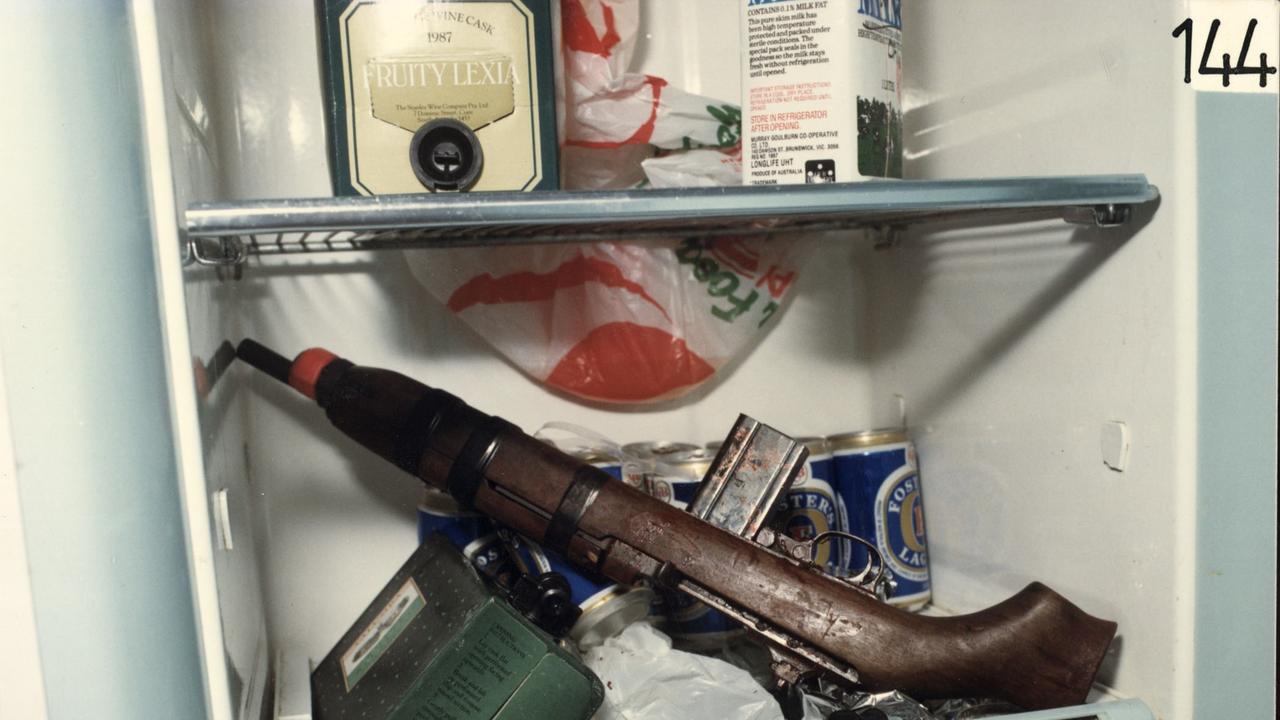

Gioia, a father of four and much smaller than the killer, saw his chance. He jumped on Vitkovic from behind, pinning his arms. The wounded Carmody rushed to help. He wrestled the rifle from Vitkovic and handed it to a woman who hid it in a refrigerator.

Vitkovic lunged at a window already broken by gunfire. The brave Gioia hung on to his legs as long as he could, but then the shooter kicked clear and plunged to his death.

On the street, armed police arrived just in time to see his body hit the footpath. Frank Vitkovic’s pain was over, but for eight families a lifetime of horror and sorrow had just begun.

More Coverage

Originally published as The schoolboy grudge that sparked a massacre