Mitchell Toy: How Cold War fears sparked Australia’s most controversial vote

When Cold War paranoia was in its infancy, a move by Robert Menzies’ government to change the constitution became the most contentious referendum in the nation’s history.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For the 45th time since Federation, Australians will soon be asked in a referendum if they want to change the country’s constitution.

Those in the “yes” camp, in favour of an Indigenous voice to Parliament, are under no illusion about the challenge they face.

Of the 44 previously proposed changes to the constitution, just eight have been successful.

But there is little doubt the most controversial referendum Australia has ever held was the 1951 vote on communism.

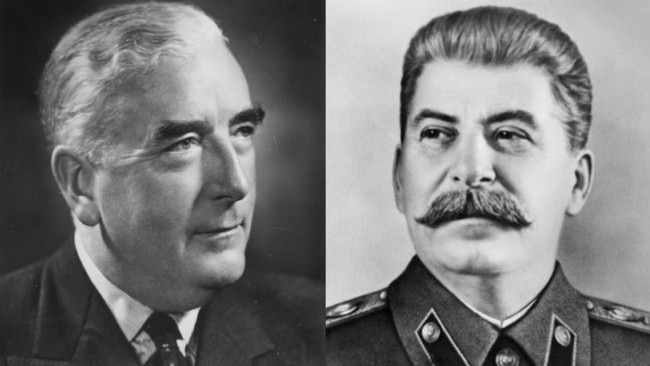

At a time when Cold War paranoia was in its infancy, it was a move by Robert Menzies’ Liberal government to change the constitution so they could ban the Communist Party outright, single out its supporters and make special laws to silence them.

Reds under the bed

Even before the Cold War, conservative Australian politicians were worried about the creeping local influence of socialism and communism.

May Day rallies and popular meetings in Melbourne were a big contributor to the paranoia.

Throughout the war, and after it, the communists openly flouted their love of Lenin, Stalin and the Soviet regime.

The Communist Party of Australia had formed in 1920 and was steadily gaining support.

By the late ’40s, as the West stared down Stalin, the Australian communists were viewed by the newly formed Liberal Party as outright threat.

Robert Menzies, who hailed from the tiny town of Jeparit in rural Victoria and was Australia’s longest-serving PM, saw just one way forward.

He drew up legislation to totally ban the Australian Communist Party.

In a move criticised by many as antithetical to the principles of freedom on which the Liberal Party was founded, Menzies pushed for the Communists to be treated as a special case, and their registration revoked.

In a speech to parliament supporting the Bill, he read out a list of known communist “traitors” who would be brought to heel by the new laws.

The ALP, to the surprise of many, got behind the legislation and supported it through the Senate.

But they only did so after the Bill was changed to prevent the federal government from identifying and persecuting individual communists.

For a short while, it looked like the communists were banished from the political scene for good.

But a court challenge soon found otherwise.

Taking the matter to the High Court, the Communist Party argued the legislation was unconstitutional.

The Liberals claimed their new law held water because the constitution gave them power to legislate about certain defence issues, and the Communist Party was a threat to the nation’s security.

The communists won and the High Court overturned the law with a vote of six to one.

But Menzies wasn’t done yet.

If the constitution didn’t allow him to ban the Communist Party, there was one trick left up his sleeve: change the constitution.

So was born the 1951 referendum on communism and communists.

This time the ALP didn’t support it, and pointed to Menzies’ earlier speech which, as it turned out, incorrectly identified certain people as communists.

Labor claimed the move would lead to overreach that could see anyone labelled a communist with very little evidence.

Others in the “No” camp openly accused Menzies of fascism.

Meanwhile the “Yes” campaign claimed banning communists was the only sure way to prevent Stalin gaining a foothold in Australia.

Ultimately the “Yes” case failed, but not by much.

The vote was held on September 22, 1951, and the “Yes” case won 49.44 per cent of the vote compared to the “No” case’s 50.56 per cent.

Marxist dream lives on

The last successful referendum in Australia was the 1977 vote to alter the framework of the Senate.

The issue dealt with the process of replacing Senators who vacate their seats mid-term, which had been a contributing factor to the 1975 constitutional crisis.

The most recent referendum held in Australia was the 1999 republic vote in which the “No” case won by 1.2 million votes with more than 60 per cent of the total.

The “Yes” case failed to get a majority in any state or territory except the ACT.

There still exists a communist party in Australia, founded in 1971 to operate alongside the party Menzies attempted to ban, which eventually folded in 1991.

The party remains committed to Marxist and socialist ideas and in June this year sent a letter of support to Chinese President Xi Xinping for the Chinese Communist Party’s 101st anniversary.

“On this special occasion, we salute the long history of struggle and sacrifice of Chinese Communists to fight relentlessly for a socialist future and to uphold the lofty values of communism,” the letter stated.

“More than ever, the role of the Communist Party in China and worldwide, is indispensable to provide inspiration and guidance for action to achieve change.

“We warmly salute the Communist Party of China and look forward to strengthening relations between our two parties, in the joint struggle for peace, social progress, and socialism.”

Originally published as Mitchell Toy: How Cold War fears sparked Australia’s most controversial vote