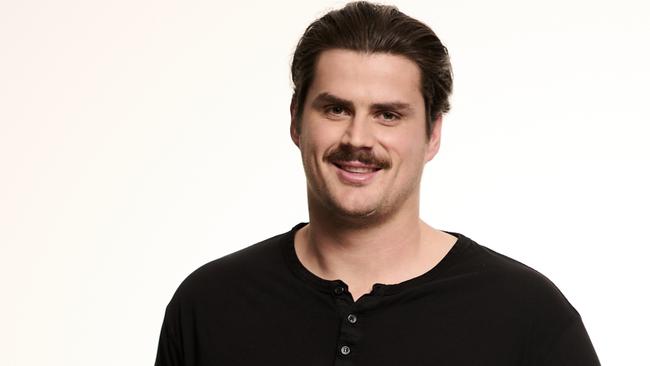

A premiership player, getting paid a million dollars a year, Tom Boyd ‘had the life’ before he quit

A premiership player on huge money, Tom Boyd had the football world at his feet. But he fell out of love with the game and “failed to cope”.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Tom Boyd’s story looked perfect on paper. A prodigious young football talent, taken No.1 in the draft and then transferred on a seven-year, $7m deal to the Western Bulldogs. A premiership player with the world at his feet. Then he retired, five years into his career. He talked about his battle with depression and anxiety. And then, over lockdown, to keep busy and avoid his mind becoming a negative influence, he started writing. As he did, he found out a lot about himself.

“For me, in my very early 20s, I had absolutely everything considered to be a success. I was a premiership player, I was one of the best players on the day, I was getting paid a million dollars a year, I had the girl, I had the life, I had everything, but it was also through that period when I was in the most difficult part of my life,” Boyd reveals. “ I failed to cope with it.”

HM: Tommy, last time we spoke we weren’t far off going into lockdown. How did two years of lockdown affect your battle with depression and anxiety?

TB: For me, one of the greatest learnings that I’ve had through all of my challenges I’ve faced is what I need in my life. And one of those things is structure.

HM: Did it take you a while to realise you needed that?

TB: Not too long – it became apparent pretty quickly. When you retire, you get taken off the club email, and then, life as a regular human starts. Initially, I thought, “This is bliss. I have no one to answer to, no one to tell me what to do.” But after two weeks, I needed to start doing something. I really needed to dive in to get some structure in my day again.

HM: Idle hands are the devil’s tools.

TB: Agreed. I managed structure through the end of 2019, my first year out of football, and the start of 2020, and then, just like everyone, my life was turned upside down. The immediate thing I missed through Covid was, again, that structure. I was scared, everyone was scared, not only about our health and our family’s health, or what was to come, but about my mental health and wellbeing.

HM: So you wrote?

TB: Yeah – I needed to be busy. I started writing this book was because I needed something to do to give my days meaning. My work had all been cancelled, university had been put on hold and everything I had in my life, like so many others, including community sport, was gone. I took it upon myself to get my thoughts on a page and take stock of the past six years of my life, particularly around my career and the challenges I faced, and get to the point where I could really put it to bed and move on.

HM: Did revisiting your career and challenges from 2014 through to 2019, putting it on paper, give you a different perspective than you thought it would, or that you had before writing it? Did it alert you to things that you weren’t aware of?

TB: Yes, it did. It’s been well documented in terms of what I went through but there’s a vast difference between talking through it and writing it down. When you write it down, you really have to dwell on the issues you faced. You have to take stock of what happened, why you were feeling like you did, and digest it all. That was a new experience for me. There were multiple times where I was sitting there, and I’d spend 20 minutes where I wouldn’t write anything because I almost had to visualise and re-engage the emotions I was feeling at the time. It was seriously confronting – not something that I expected. I’ve spoken about this 100 times – I’ve shared it, everyone knows what happened – but to write about it, alone, was much, much more challenging and enlightening for me. For me, it was liberating and healthy to do it. It’s rare that we have moments in our lives which aren’t so busy, that we have enough time to sit back and truly intimately reflect. I was lucky that I took up this project and started to do that.

HM: Is there anything that you look back on and think, “I didn’t realise that was the catalyst for this?”

TB: I got asked a question recently: “What would you have done differently?” I think that’s because everyone wants an easy answer to why they feel like they do. But I think the biggest mistake that I made was I consistently and constantly thought that my story was unique.

HM: Meaning?

TB: That I was any different to others and should have felt ashamed of having depression and anxiety. In many ways my story was slightly different. I was a No.1 pick, I came out of a highly touted junior career, I was the first player to really oust myself out of a contract in my first year at a football club, and, of course, the seven-year contract, and then winning the premiership, were all unique. But what I failed to grasp was that the emotional and human experience that I was going through was one that people go through every single day.

HM: As I read the other day, “Seven billion people experienced today differently”.

TB: Exactly, so why should I feel embarrassed by my story? No one should feel embarrassed by their story. Being open to actually hearing other people’s wisdom around how to support myself and how to work through the human side of things, was something I did really, really poorly. I consistently shut people out and tried to do it on my own. The reason I did was I thought I had to.

HM: Is that one of your biggest learnings?

TB: The biggest. I needed people to support me. I took too long to get it. There is a strength and wisdom in accessing the support of others, rather than just trying to do it on my own.

HM: Do you think if you were more open throughout your career, invited people in, and got help, you would have played for longer?

TB: That’s a really good question. Fundamentally, there’s a massive difference between junior and senior footy. The highly competitive, super performance-oriented nature that professional sporting clubs have really diminishes the ability to have that community feel. Some people handle it well, and some don’t. I didn’t. It’s a business, and it’s our livelihood, and it’s cutthroat. It wasn’t for me. I don’t know if I would have played longer, but certainly I would have coped better.

HM: How could you have played your cards differently?

TB: I should have spent copious amounts of time with my assistant coaches, asking for help, working through the problems I was facing, talking through what I was feeling and dealing with the pressure better, instead of saying, “I’m fine”. Repeatedly. It would not only have helped my football, but it would have helped me as a young person, a young man, trying to work out who I was.

HM: Did you leave because of your depression and anxiety becoming overwhelming, or because you wanted to do something else?

TB: I probably didn’t know the answer of that until I wrote the book. I now know for sure. I left not based on depression or anxiety. I was just ready to move on. I had fallen out of love with football and didn’t want to play it any more. Itseems odd. It’s all I ever wanted to do but I just didn’t want to anymore. It’s like when you are in a relationship that you know has to end – for you, and for them. I would also say that for whatever reason in my life, I am acutely aware to turn the page and start the next chapter. In 2019, it felt like the time to do exactly that.

HM: Have you had any horrifically low points since retirement?

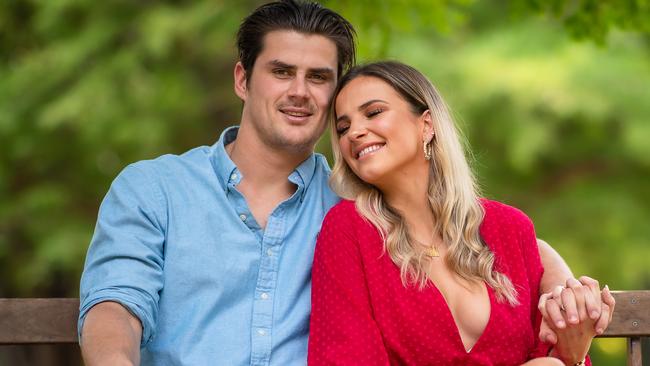

TB: Not horrifically low. There were certainly moments through the pandemic where I was frustrated. Once we started going in and out of lockdown, I kept getting hopeful that my work would get back to being consistent, then it didn’t, and then I tried again. That uncertainty around whether we were going back to normal or not was quite challenging for me to deal with in a work sense. I have the most amazing girl in the world in Anna, at home, who has been incredible in supporting me for several years now. Booking a wedding three times is enough to deal with.

HM: You are a self-analyser. Do you feel professional sport in 2022, given the scrutiny, the analysis, the constant chatter, isn’t suited to some people?

TB: Definitely. When I got to the league, I was such a chronic over-thinker. My brain was always a couple of steps ahead of my body. There’s a reason, in part, that my career didn’t work out, and my personality is part of it. I have been quite honest and frank that I didn’t have the mental fortitude to play AFL footy for a long time. I’m not ashamed of it, it’s just a reality of where I was at. I couldn’t cope with people putting me in the box of a footballer. People were judging my merit as a person based on how many kicks I’d get on the weekend, as opposed to the work I was doing every single day. Some people’s personality types are more suited to playing good footy, and playing good footy for a long time.

HM: What’s Nowhere to Hide about? Is it football, life, mental health, or a combination of all?

TB: It’s a combination of all. What I wanted to do when I set out about writing this book was to really try and humanise the athlete experience, at least from my own perspective. We so often in society look at people based on whatever metric of success that we think is appropriate and go, “that person is happy because of X”, or “that person must be going well because of X, Y and Z”. For me, in my very early 20s, I had absolutely everything considered to be a success. I was a premiership player, I was one of the best players on the day, I was getting paid a million dollars a year, I had the girl, I had the life, I had everything, but it was also through that period when I was in the most difficult part of my life. I failed to cope with it.What I really wanted to do was get into the gritty details of what was going through my head, through many of the difficult parts, but also the good bits. It’s not a dark book, it’s frank and open, and I really hope that what it does is shed light on the fact that regardless of who you are, your experience and the challenges you face are not necessarily unique, but are just as important. Deal with them and get the support you need. Whether you are an AFL footballer, whether you’re starting your first job at Maccas, it really doesn’t matter.

HM: Which is your best chapter? You must have a chapter where you go, “I nailed that”.

TB: Selfishly, I like the last one, because I think I really nailed my retirement speech …

I left everyone feeling happy. I don’t know why I had the self-awareness to do it at the time, but I was conscious that I hadn’t played for 20 years, or 15 years at the Bulldogs. I’d been there for four-and-a-half seasons, and I didn’t want it to be this big song and dance about how I was so sad to be leaving. I wasn’t sad, I was ready to move on. I really wanted it to be clear: people in the building kept me there, and they are the ones who supported me and kept me playing as long as I did. Selfishly, the last chapter is the one that stands out for me.

HM: Advice to those battling with external pressures, footballers or others?

TB: One of the things I’ve really tried to do since I’ve finished is not give advice to people. I didn’t nail my career; one of the lines in the book is basically that my career by many metrics was a disappointment. The reason for that is not just that I didn’t get to the 15-year career that I wanted to but also because I thought that football was going to offer me something that it didn’t, which was true, consistent enjoyment and satisfaction. That wasn’t the case. My only words of commentary, more so than advice: remember that football is a part of your life, and that there are so many things that need to happen outside of the game for you to be able to accomplish what you want to do on the field, including looking after your overall development as a human, whether that be education, the ability to have self- awareness, maturity, respectful relationships with others. All those things matter, and you can’t put them on the backburner just so you can play the best footy that you want. Long term, it won’t serve you as well as focusing on the whole picture.

HM: How has fatherhood reshaped your thinking?

TB: It’s the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. It’s two-fold. One, Armani is an incredible sight to see every single morning when she wakes up and smiles at me, but secondly, for my fiance, to see how amazing she has been as a mother, and Anna is only 25. To see her dive straight into it like she was genuinely born to do it, it’s just a whole other level to our relationship together. I couldn’t be happier. I’ve never had any shyness about giving stern feedback to people who said my life was over. Mate, why would you say that to me? I’m excited, I am keen to dive straight into fatherhood, and it’s been everything that I could have hoped for and more.

HM: What’s next for you? Is the wedding that’s been reshaped three times still on?

TB: It is. We are finally going to do it in December. It’s quite funny trying to reconnect with suppliers that you’ve spoken to three times. In 2020 we were due to get married, and in that year, weddings were opened to 100 people the day before we were scheduled to be booked in. We’d already postponed it by that stage. Then Anna was pregnant, but she wasn’t going to be five months pregnant at her wedding. Then this year we don’t have any more excuses, so we’re going to get it done in December down in Portarlington. Anna’s family are coming from all around the globe, so will mine, and it will be nice to reconnect with everyone after what’s been a tough couple of years.

HM: Where’s Anna from?

TB: She’s from Anglesea. We got our holiday property in Anglesea in 1997. Anna’s family moved to Anglesea in 1998, and they bought the house next door to us. I have known Anna and her family, not super well, since we were 18-months-old. I know all her five brothers. It’s crazy. Life is good.

Nowhere to Hide comes out on August 2 and is available for pre-order now.

Originally published as A premiership player, getting paid a million dollars a year, Tom Boyd ‘had the life’ before he quit