Not afraid to have a little bit of fun with the inevitability of crime through his practice – and t-shirts for his staff – Bill Potts might be the Gold Coast’s very own ‘Better Call Saul’.

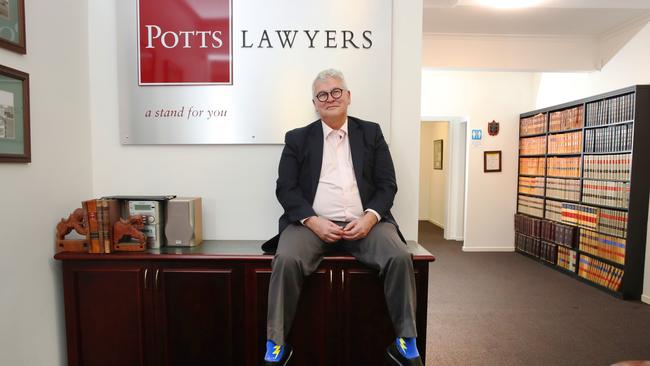

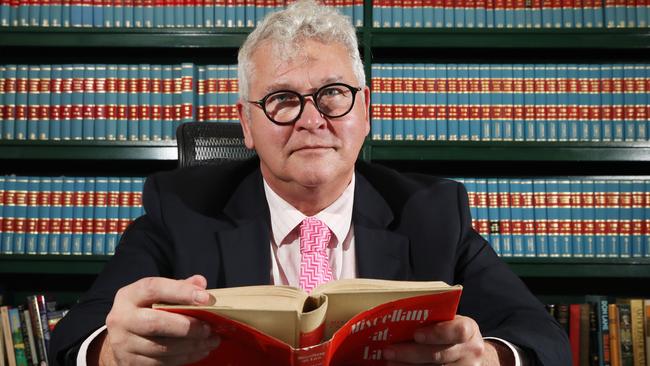

The Gold Coast solicitor, who recently celebrated his 40 years of practice, has slowly built the largest criminal firm in the state.

Along the way he has represented notorious crooks such as fraudster Christopher Skase, bikies and those down and out.

He has even done a stint as Queensland Law Society president.

The Bulletin sat in his top-floor office – where a bookshelf covers an entire wall – to talk about his biggest client, the trials of a law career, juvenile crime and that picture with the T-shirt slogan.

Gold Coast Bulletin: You’re celebrating 40 years as a solicitor. Congratulations. How does that feel to such a milestone?

Bill Potts: Well, I say that when you get to the top of the mountain, the view is wonderful. But I feel a great sense of satisfaction, both for marking 40 years and what is a very, very difficult profession, but almost impossible job by most people’s standards. And to actually have made sort of half a success of myself.

GCB: Not many solicitors make it to 40 years in the profession, particularly in the criminal area. Why?

BP: Criminal law particularly is very difficult law (and) has become much more complex in the 40 years I’ve been practising. The real difficulty is that criminal law is brutal, and it comes with a personal cost. It destroys, more often than not, your relationships with people you love. And it leaves you sometimes in a place which is cynical and hard. To actually be a criminal lawyer, you have to have, in my view, a true belief and that is a belief in the justice system. But criminal law particularly comes with a very high cost and it’s not one which everybody can pay. I’ve been lucky enough to pay it, I suspect, but it is something that also has regrets.

GCB: Are you able to speak to those regrets?

BP: It’s a misunderstood job. Because quite often people think that if you’re acting for a murderer, you must approve of murder, which is nothing to be further the truth. People somehow associate you with your clients, which again, nothing could be further from the truth. It has a deleterious effect upon family and friends because more often than not, if you’re dealing with the very grubby side of life, where you’re dealing quite often with violent and dangerous people, it hardens you and means they become cynical. Sometimes, believe it or not, I even find myself cross-examining those people I love. Not because I want it but all of a sudden it’s like, by reflex, that voice comes out of my mouth and it doesn’t always make for good relationships.

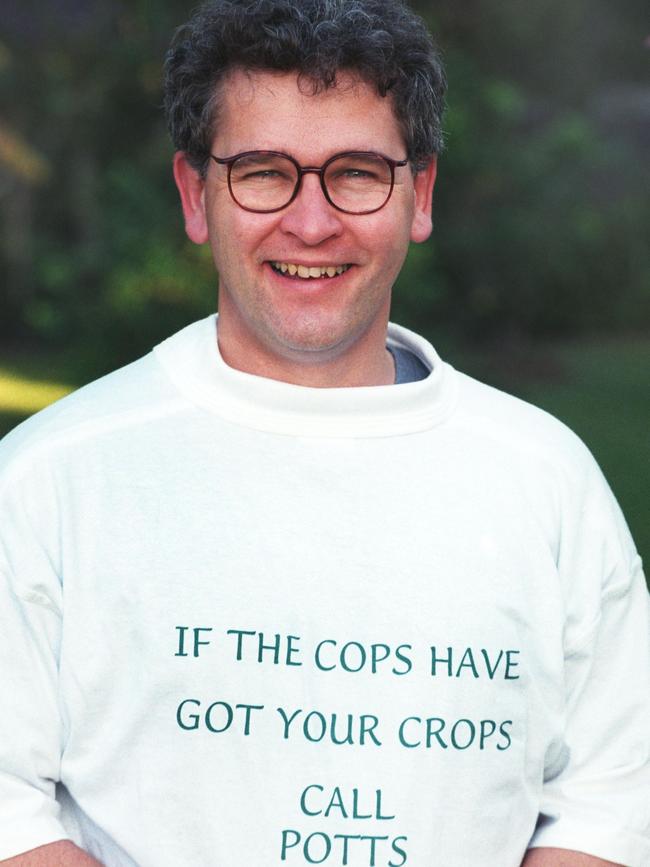

GCB: What can you tell me about this photo of you taken in 2007 wearing a shirt which says “Cops got your crops, call Potts”?

BP: I remember that very well. It was taken in my backyard. I’m so much younger then. I’m older than that now. Every year at Christmas time I would give a present to members of the staff. It was a T-shirt. So this year when I did it I had: “If the cops have got your crops, call Potts”. A later one was, “Reasonable doubt at a reasonable price”. I had another one that said “Tell ’em nothing, taken it nowhere”. The last one I did said, “Potts Lawyers, we believe you”. I always thought it was funny and it was for the staff. But it is amazing the number of times people come up and say to me that they remember it. The other wonderful thing about that is I was slimmer and had brown hair, so things have changed and not always for the better.

GCB: What are some memorable moments from the courtroom?

BP: The trouble with memorable moments in courtrooms is they always seem funny at the time, when you often accompany with ‘you had to be there’. I’ll tell you one story very quickly. I was cross-examining in the magistrates court one day and asked a particular question. The person answered “no”. And at that very second, the entire building was hit with lightning and the lights went out. After about 10 to 15 seconds the emergency lighting came on and the magistrate was shocked. I was shocked. The defendant was shocked. I looked at him and said: “Did you just lie?” Of course, he goes “no, no, no, it wasn’t me”.

GCB: Did one of your clients save a juror’s life?

BP: I had a client who was very famously a medic in the Army and during the trial, one of the jurors had a heart attack. The judge, who clearly hadn’t listened too carefully to the evidence, said: “Does anyone have medical experience?” My client jumped out of the dock … (and) in that moment showed incredible courage and calm, and literally saved the juror’s life. The prosecutor asked for the jury to be discharged because nobody, he explained to the judge, could find him guilty after witnessing his heroics.

GCB: You represented Christopher Skase and have spoken about him before. Is there anything you can tell us about trying to wrangle something that high profile?

BP: Mr Skase, who’s now dead, I can tell you two things about him. One was he was a very difficult client to deal with. He had very high expectations. He wrote a book … I can’t remember the exact title. He claimed he was in the watchhouse, had been maltreated by police, was essentially a victim of the justice system and, because of the fact that he had to sit in a cell with other prisoners, that this was the reason why he fled Australia.

But the real truth was I spent the entire time with him and they treated him very well. The point of all of that is that when you’re acting for high-profile clients, they perhaps know that there is more at stake and want their lawyers to be serious and to do a serious job. But ultimately, there’s a sense of, I suppose, almost ridiculousness.

GCB: What about other memorable clients?

BP: I can say this … I had acted for just about every “d” in sight. That’s dingbats, dropkicks, druggies, desperados, detectives, you name it I would have acted for them.

… I’ve lost many clients to suicide, because of the stress of being charged or being accused. I’ve acted for people who have shown incredible callousness and psychopathy. I’ve acted for people who have been caught up in things way beyond their control and found themselves doing things which they could never have contemplated in their quieter and better moments. So I don’t want to name them simply because I think my clients deserve respect. I’ve never wanted to be seen as a celebrity lawyer or as a lawyer to the stars or the, you know, the great. I want to be, and I’ve always been, you know, the lawyer for everybody.

GCB: Why did fraudsters seem to be attracted to the region?

BP: The Gold Coast is a remarkable place. When I arrived here in 1981 it was a smaller place and everybody knew each other. The old line of it being a sunny place for shady people, is perhaps apt. The truth of it is that the Gold Coast is one of those places that’s gone from barbarism to decadence without the intervening stage of civilisation. And that means all the glitz and glitter, the extreme wealth and extreme poverty seems to attract both colourful people and people on the make.

It’s the most visited place in Australia and we have an awful lot of crooks who come here on holidays. Consequently it’s a fascinating place to practice criminal law.

GCB: Is there any difference between representing the Skases and high-profile names and the regular guy off the street?

BP: Not to me. One of the truisms of life is quite often when you’re a criminal lawyer, you start off acting for the poor, the weak and the vulnerable, and the better you get the job you end up acting for the wealthy and the permanent criminals. They do bring an entirely different attitude to their circumstances. Most people who have found themselves trapped in criminal law just want help. They want someone who will make a stand with them.

GCB: What are some of the biggest changes you’ve noticed over your career in the Southport legal precinct?

BP: It used to be a place (Gold Coast) that, back in the ’80s, was obviously and startlingly corrupt. The police force was essentially corrupt. You could see it in action every single day. Some people were being prosecuted, others no. Some people being let go for offences they clearly committed. You know, just weird results. And it was quite clear to the public and eventually to even the Queensland government that corruption was afoot, so the Fitzgerald inquiry changed the entire landscape of the Gold Coast, and it meant that the police had to become more professional. Unfortunately, it made the crooks become more professional.

GCB: Have the police become more professional?

BP: I think they have. Police tend to fall in a series of baskets. They are often people who become police officers; people who become lawyers, even for the wrong reasons; people whose personalities simply aren’t suited to it. That’s not always a good thing. But there are far more police who are professional, better trained and who see the job of being a police officer as not being their final career.

GCB: There has been a lot of juvenile crimes, particularly around carrying knives or stealing cars. What can be done to curb that?

BP: One of the definitions of insanity is to do the same thing over and over again and expect a different result. So the cries of lock them up and throw away the key, we know don’t work. It actually brutalises people that come out worse than they went in. For some of them, at least it’s a sign that they’ve transitioned to adulthood because they’d been in jail.

I understand the real anger and the desire essentially for retribution (for victims of crime). But if we take an eye for an eye, everybody is going to end up blind. So what we actually have to deal with is why is someone carrying a knife? Kids don’t wake up at the age of 10 and decide to be a criminal. Often it’s because they have been brutalised in their own homes. Often because they, their parents have been brutalised before them and are absent in jail or have fled the scene.

There is the outrage of drugs, boredom, lack of education, lack of food, any number of issues. So I think it’s really important that we, rather than just simply say “well, that’s a terrible thing, tut, tut, tut”, we actually engage with the causes of that crime and deal with that. That is something which is a multi-decadal problem, a multi-decadal solution. It won’t be solved and has not been solved in the 40 years of my practice. So I think we actually had to look at it and do something different.

GCB: If there’s one thing you could have done differently over the last 40-odd years, what would that be?

BP: Learn to play guitar. My guitar teacher tells me if he got me when I was 15, I could have been a child prodigy. These days, I’m just a bum. But yeah, I think what I should have done differently is spent more time looking at myself, servicing my family rather than tilting at some of the legal windmills that are out there. Having said that, I’m proud of what I’ve done. I hope I’ve made a difference. And I hope I’ll continue to make a difference in the future.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Sharks unveil huge new stadium, $500m mega development

Southport Sharks has unveiled plans for a near-21,000-seat stadium and three residential towers in a massive redevelopment that could reshape the Gold Coast's sporting landscape.

Revealed: All Coast’s options for solving gridlock nightmare

The Gold Coast's population will surge by 350,000 in two decades, but the city's transport blueprint remains in limbo after light rail's dramatic cancellation. FIND OUT MORE