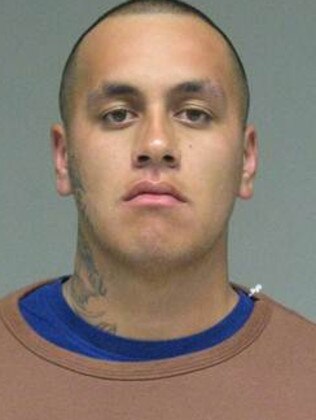

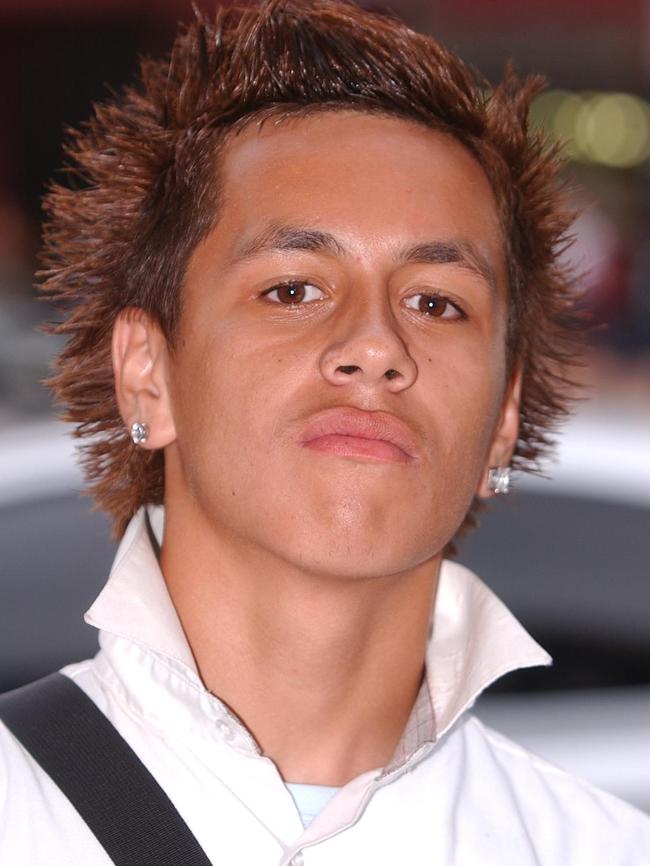

LIONEL Patea was only 16 years old when he first became known to police.

In the decade to him pleading guilty to the murder of high school sweetheart Tara Brown, officers got to see a great deal of him.

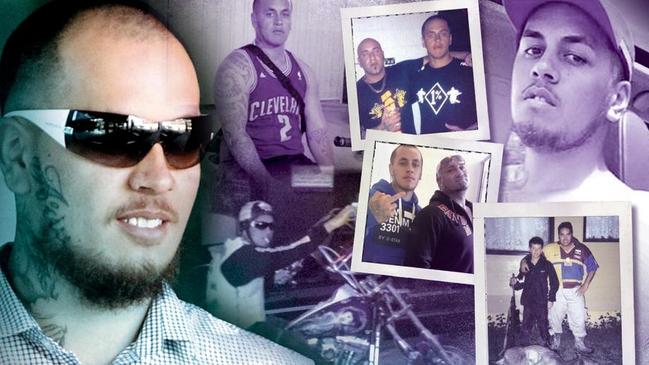

For the first time, the Gold Coast Bulletin can reveal Patea’s struggle with self-harm and suicide, the relationship with his father, his temper through his teens and life as a “respected” bikie enforcer, where extorting money for debts netted him a base salary of $250,000 a year.

CHAPTER 1: TARA’S EIGHT DAYS OF TERROR ON RUN

CHAPTER 3: TARA BROWN’S DESPERATE ESCAPE PLAN

CHAPTER 4: TARA WAS ‘EVERYTHING TO ME’: PATEA

CHAPTER 5: THE LITTLE GIRL WITHOUT HER MUMMY

Through it all has been one common factor, his desire for control — and never was it more evident than around women.

THE BOY, HIS DAD AND THE GUN

Lionel Patea came to the attention of authorities in September 2008 when he knocked out another student during a schoolyard fight at Keebra Park State High School.

He was 16.

The fight was triggered by a racial slur.

Before that, Patea had committed several petty thefts. Nothing violent.

Born in Dandenong, Victoria, in 1991, Patea grew up in Whanganui on New Zealand’s North Island before his family — including brother Nelson and sister Jessica — settled in Ashmore.

Family friends say Patea’s relationship with his mum was good.

He always took her advice.

Patea and his dad. That was different.

“He had a weird relationship with his father,” a source close to the family says.

Despite numerous postings on social media about family and friends, Patea only ever shared one picture of his old man.

It was in December 2014.

In the picture, Patea doesn’t look older than nine or 10. He is posing with a large gun in his right hand. A dead animal lies bloody at the pair’s feet.

“Me and the old man getting us a feed back in the day lol,” Patea writes.

“Awa hunters hehehe,” his father, Andrae Patea, replies.

Patea isn’t smiling in the picture but dad is beaming with his arm around the boy. He’s wearing a footy jumper and a pair of dirty old boots.

By 2015, it is a different story. Patea’s father is rarely seen at his son’s court hearings for the murder of Tara.

THE FOOTBALLING FAMILY

At Keebra Park State High School, Patea was a promising rugby league player, representing the South Coast Maori Rugby League team. But he threw it all away once he graduated school in 2009.

His family were heavily involved in the Nerang Rugby Union Club and as he grew older, some of Patea’s closest mates became professional footballers. On Facebook, he posted his footy tips, backing the Sydney Roosters and Manly Sea Eagles in the 2014 season.

FIRST SIGNS OF MENTAL ILLNESS

It was clear from early on that Lionel Patea saw the world differently to others.

Friends recall Patea having health problems as a youth, which caused problems with his temperament.

As a child, he would argue the most minor point across the family table.

“Everything has to be Lionel’s way,” a friend remembered.

Sources close to Patea say he began self-harming at 16 and tried to kill himself after a girl broke things off.

“He tried to hang himself and then took a million Panadol or something. It was over a girlfriend.

“He’s never been very good at dealing with breakups. He seems to have a difficulty with letting go.”

At a court appearance last year, Patea’s long-term defence lawyer, Campbell MacCallum, a principal at Maloney MacCallum Lawyers, laid bare Patea’s history of self-harming.

THE DEBT COLLECTOR

After graduating from high school, Patea searched for his place in the world.

“After Keebra, he got a bit lost and got involved in a rough crowd,” a school friend says.

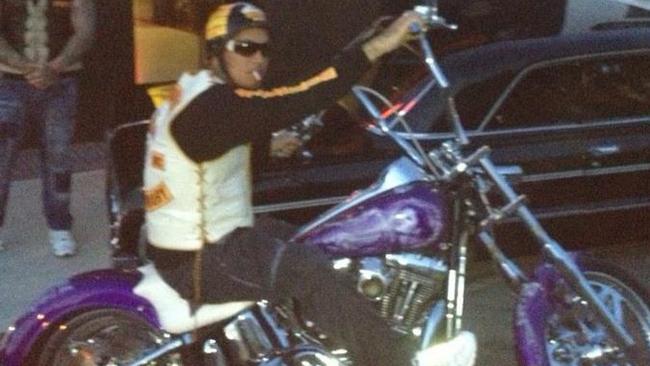

Bikie sources track Patea’s involvement in gangs back to when he was 14 years old.

Some say he was getting into trouble around Coombabah and Nerang.

“He had an apprenticeship with the Mexican Soldiers,” a source says. “He established himself in the drug network. He was a standover and collector.

“The Mexican Soldiers are the feeder club to the Bandidos. He established himself as a link between the two gangs.

“Running drugs and collecting is way of getting a leg up.

In the Bandidos, they guarantee $250,000 a year as a starting salary.

It involves extortion, delivery and pick up.

He was quite a substantial dealer on the Gold Coast. He was very well thought of by the Bandidos.”

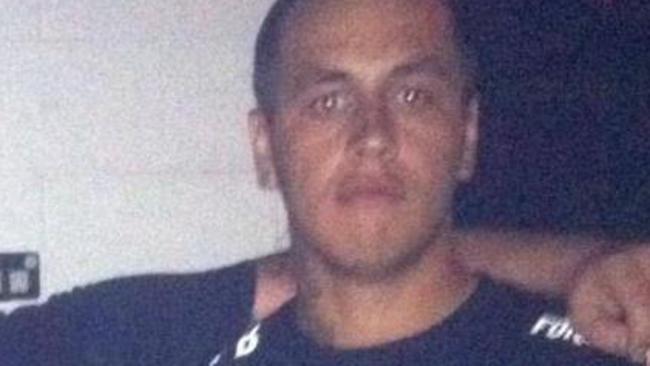

By 19, Patea is heavily involved with the Bandidos.

He quickly rose through the ranks because of a propensity for violence. Patea wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty.

“He became a sergeant-at-arms at a very young age,” a police source says.

“This was partly because at the time they didn’t have the numbers but also partly because he had a reputation for being a violent operator.

“He was a debt collector and had a good reputation in the criminal world. He would turn up and enforce debts on people for the Bandidos.”

In 2011, Patea was given a suspended jail term after being charged with fraud and driving offences but was released on parole immediately.

THE VIOLENT FATHER

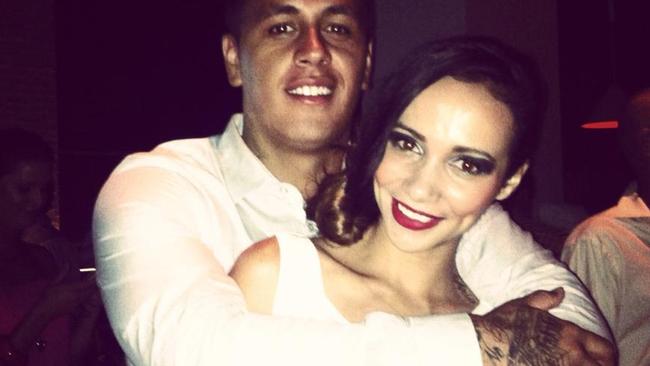

By2012, Patea and Tara have a baby on the way.

The dad-to-be was becoming violent and the dynamic of their relationship began to change.

The boy Tara met in high school is gone. She didn’t sign up to have a baby with a bikie.

Patea’s family hear their boy has been knocking Tara around while she is pregnant.

They are furious.

People start talking of a video showing Tara cowering behind a car after being hit.

Police take out a temporary protection order between the pair in April.

It becomes permanent in July, two months after the birth of their daughter, Aria.

Later that month, Patea is sentenced for breaching the order by using a carriage service to make threats to kill Tara.

He is ordered by a Gold Coast court to serve one month imprisonment, but is released on parole immediately.

BROADBEACH BRAWL

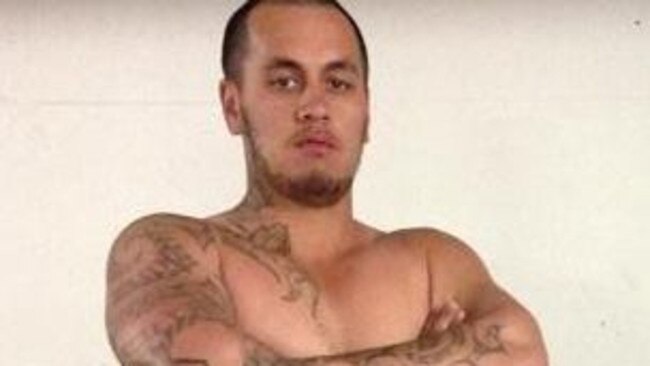

Patea’s rap sheet is growing, as is his role in the gang.

Police later describe Patea as a “key player” in the infamous 2013 Broadbeach blitz that changed the Gold Coast criminal landscape forever.

At the time, there were conflicting reports of Patea’s involvement in the riot.

Some said Patea wasn’t even there.

Others say he was front and centre of the Bandidos’ lynch-mob that stormed the Aura Tapas and Loungebar to confront rival gang associate Jason Trouchet.

It can now be revealed Patea was one of several bikies who turned up at the Southport Police Station after the brawl to demand the release of fellow gang members.

Patea confronted police before being taken into custody.

Police described the Broadbeach riot as an “eruption of violence” so serious officers considered drawing their guns on “a wall” of bikies.

Patea was among more than two dozen bikies charged with riot in relation to the brawl.

He later pleaded guilty to public nuisance in the Brisbane Magistrates Court in 2015 and was fined $2500.

GLADSTONE AND LEAVING THE CLUB

Patea breached the domestic violence order between him and Tara several times before it expired in July 2014, but as Aria was approaching her second birthday the pair decided to give things another go.

In November 2013, Mr MacCallum told the Southport Magistrates Court his client had quit the Bandidos after facing scrutiny from police.

The court was told Patea had surrendered his jacket and sent his bikie paraphernalia to the national club secretary in Melbourne.

“He hasn’t come to court saying it, he has actually packed up his memorabilia and sent it off to Melbourne,” Mr MacCallum said. “It’s significant.”

After pleading guilty to driving without a licence as a repeat offender in 2014, Patea began working in the mines at Gladstone and seemed determined to give his family a better future.

“Despite everything, he was really a family-orientated person and he left to work in the mines because he wanted to keep the family together,” one source says.

Facebook posts from 2014 show happy snaps of the family at the beach and images of Tara and Aria riding a quad bike. “Can’t wait for cuddles,” Patea writes, presumably from the mines.

Other pictures show Aria and Tara smiling and high-fiving each other.

“My 2 favz,” he captions one image.

Another post is of a card Tara and Aria post Patea for his birthday. “Miss you,” it reads.

From the outside, things look good. But they don’t stay that way for long.

TARA SLIPPING AWAY

After the argument over another man at Auckland Airport in 2015 Patea knew he’d never have Tara to himself again.

“He refused to let her leave,” a source close to Patea says.

“He knew she would get boyfriends. She had one in New Zealand and two on the Gold Coast.

“He had massive jealousy issues and, for him, he knew she was moving on and he couldn’t handle it.”

Days before Tara is murdered she offers Patea a new custody agreement with Aria.

It’s a better deal than the pair ever would have struck in court. Patea signs.

“He was just blank,” a source says.

“I knew something else was going on with him. It was just like he didn’t really care.”

The thought of Tara being with other men possessed Patea and he needed to get back control.

BEHIND BARS AND ALONE

Patea’s mental health rapidly declined once he was in jail.

From early on, he was put in protective custody at Brisbane’s Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre.

A police source says Patea was initially placed outside the mainstream prison because he “wouldn’t be able to protect himself” due his self-inflicted stab wounds.

However, Patea has spent little time in mainstream custody due to long-running battles with prison guards.

He cannot contact Aria and has no access to books or even a bible.

In November 2016, the Gold Coast Bulletin revealed he was receiving weekly visits from a prison psychologist after being diagnosed with being “disturbed in terms of thought processes”.

Earlier in the year, he was admitted to Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital and kept overnight on August 18 — his 25th birthday — after a confrontation with guards who were returning him to the detention unit after he had been socialising with other prisoners.

Patea allegedly had to be restrained and taken to an interview room where he was kicked by guards while on the ground.

He now takes medication for nerve damage to his neck and back.

Prison sources said Patea had also put soap on the floor of his cell and attempted to spar with guards.

“He is seeing a (psychologist) weekly but he is not getting the specialised care we believe he needs,” Mr MacCallum said last year.

In 2016, he pleaded guilty to an attack on a fellow prisoner in May last year after burning him with water that had been heated in a microwave.

The other prisoner was on remand for offences including torture and animal cruelty, but Patea thought he was a convicted paedophile.

GETTING TO GUILTY

Despite a confession to running Tara off the road and more than a dozen witnesses to her brutal bashing death, Patea gave his legal team instructions to list the matter for trial.

Patea was willing to enter a plea to manslaughter, but the Crown refused.

The case was too public to cut a deal.

It wasn’t until the 11th hour that Patea indicated he would plead guilty to murder.

He wanted to tell his story. Part of that was about control.

He wanted everyone to know his girlfriend cheated on him and that’s why he killed her.

THE PATEA CRIMINAL FILE

2010: Aged 18, Patea is pinged for public nuisance and given a $200 fine.

A month later, in July 2010, he is sentenced for unlawful possession of suspected stolen property. He is fined $600 and has a conviction recorded for the first time.

Also in 2010, a temporary domestic violence order is taken out by police at Beenleigh between Patea and another woman, which later becomes permanent.

In the same year, he is given a period of probation after being charged with wilful damage and breaching a domestic violence order.

2011: Patea is sentenced for unlawful use of a motor vehicle, driving without a licence and fraud. He is given a six-month jail stint for the fraud in November 2012, but is released on parole immediately. Also ordered to pay $1640 in restitution.

2012: In April, police take out temporary protection order between Patea and Tara Brown. The temporary order was breached in July and Patea was charged for using a carriage service to make threats to kill Tara.

He was sentenced to one-month imprisonment, but released on parole immediately.

The order between them became permanent later in July, two months after the birth of the pair’s daughter, Aria.

It was breached several more times before it expired in July 2014.

In November 2012, Patea, 21, fronts court after breaching his probation for a criminal matter. Fined $750 and ordered to serve two months behind bars. Again, released on parole immediately.

2013: By September, Patea becomes a key figure in the bikie world. Among several Bandidos charged with riot after a group of bikies stormed the Aura Tapas and Loungebar in Broadbeach to confront rival gang associate Jason Trouchet.

Patea would plead guilty to public nuisance in the Brisbane Magistrates Court in 2015 for his role in the infamous bar-room blitz and was fined $2500.

2014: After being caught driving without a licence several times in the past, Patea pleads guilty in the Southport Magistrates Court in February to driving without a licence as a repeat offender. Fined $400 and disqualified from driving for two months.

September 2015: Aged 24, Patea charged with the attempted murder of Tara Brown.

The charge is later upgraded to murder after her death. Committed to stand trial in November 2015.

2016: In November, Patea sentenced to 18 months jail in the Southport Magistrates Court after pleading guilty to assault occasioning bodily harm following a hot water attack on a fellow prisoner at Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre in Wacol.

The man was on remand for offences including torture and animal cruelty, but it is understood Patea mistakenly thought he was a convicted paedophile.

OPINION: How GC can ‘maximise every opportunity’ ahead of 2032

The Gold Coast must capitalise on early investments in public transport, community venues, new tourism experiences, enhanced tertiary education and leading-edge technology, writes Tom Tate

‘Golden opportunity’: Why this is our most important two years

The Gold Coast faces its most important two years this century - and must extend light rail south of Burleigh and clarify its identity before the 2032 Games, a leading demographer says.