Nearly 2000 Gold Coast homes are at “intolerable” risk of being destroyed by bushfires, five years on from the devastating bushfires which devastated Binna Burra. SEE THE VIDEO

This month marks five years since bushfires swept through the Gold Coast Hinterland, destroying properties throughout the area, including the famous Binna Burra Lodge.

Binna Burra Lodge director Steve Noakes said the region was far better prepared for a bushfire than it as in 2019 but warned another major bushfire was inevitable – a matter of “when” rather than “if”.

While the region has not faced bushfires close to the intensity seen in September 2019, nearly 40 per cent of the city, or around 51,051ha is deemed as “very high, high or medium” bushfire hazard according to the state bushfire prone area mapping.

An extra 26,329ha is within 100m of a potential impact buffer to bushfires according to the mapping, which was done in 2017.

Mayor Tom Tate, who chairs the council’s disaster management committee, said lessons had been learned from the emergency.

“A comprehensive after-action review was conducted at multiple levels of government following the 2019 fires,” he said.

“The City of Gold Coast has focused its resources on implementing relevant improvements to our disaster and emergency management arrangements.”

“Since 2019, the City has invested in a new Disaster and Emergency Management Centre to further enhance our disaster response and recovery capabilities.

“There has also been a dedicated focus on augmenting our disaster recovery capability with a number of elements modelled on world-best practice.

“As chair of the Local Disaster Management Group, I have focused on ensuring our partners and the City are well prepared to respond to any natural disaster.

A council report published in June underlines the risk of widespread property destruction remains high.

“Approximately 56 per cent of the city’s total area has the potential to be impacted by bushfire (and) this exposes approximately 41,797 structures used as dwellings, commercial or industrial purposes or deemed as essential infrastructure to varying levels of bushfire risk,” the report reads.

“However the majority of these structures (90 per cent) are located within the 100m potential impact buffer and not within the mapped very high, high or medium bushfire hazard areas.

“At the end of 2023, taking into account all planned/unplanned burns, and other vegetation treatments, bushfire consequence modelling for severe to extreme bushfire contentions across the city shows that the residual risk for the city as having 35,222 structures, not including sheds or open shelters, which can be categorised as having intolerable or tolerable levels of risk. (1827 intolerable, 33,395 tolerable).

“The city’s bushfire reduction framework identifies the need to place greater emphasis on how to better apply our improved knowledge of fire ecology and conservation given the uncertainty of how vegetation communities will respond in a changing climate.”

The report was submitted to the council’s Lifestyle, Environment, Heritage and Resilience Committee in June.

It highlights several areas which council must improve, including working more closely with the state government to periodically audit building approvals in bushfire hazard areas to ensure they have taken steps to address fire risk.

Mr Noakes said much had been done to bolster the region’s defences against nature.

“In the five years since we have had more frequent weather extremes from bushfires to severe rainfall,” he said, speaking from Indonesia.

“(Another devastating bushfire) will happen again, it’s a matter of when and how the community will be able to protect themselves from it.

“Bushfires have always been a part of life, especially in this part of Australia but in 2019 a lot of things came together and created an unusual situation.

“We were well-prepared for (the 2019 fire) but we have also learned from that and we are better prepared now but it is a mater of just being aware of the potential risks and having as many processes and systems in place to reduce that risk.”

Among the steps taken in recent years was the construction of a new community centre at Syd Duncan Parkin Lower Beechmont.

Jointly funded by the council and state government, the centre, which opens in late September, was built to be used as a hub for community information and emergency services to co-ordinate the response during a disaster.

Committee chairman and area councillor Glenn Tozer said much was learned from the event.

“Five years ago was a really dark time for this community and there is no doubt we had to come up with a bunch of serious actions to recover and get it back on track,” he said.

“We were really pleased to have the state come to the party and stump up $1.5m to help us build this, it’s a $3m project. When a disaster might come into this area, be it storms or fire, this will be a great centre which can help serve the community’s needs away from the disaster response.”

Cr Tozer said the city’s bushfire resilience working group meets quarterly to ensure fire management remains up to today.

“Following the bushfires of 2018/2019, the city engaged an external disaster management consultancy to perform an operational analysis of the city’s response.

“The report identified 19 lessons and identified 20 recommendations.

“The themes of the lessons identified were increased engagement with local disaster management group, inter-agency communication, data sharing and operability

local disaster co-ordination centre training and exercising, local disaster co-ordination centre and evacuation centre operational review.”

The 2019 fires also provided lessons for the Gold Coast Rural Fire Brigade, whose officers were on the front lines of firefighting efforts.

Kim Crow was second officer of the Beechmont Rural Fire Brigade at the time of the 2019 fires and said it still cast a long shadow over the mountain community.

“It was a tough time and a lot of people still have PTSD from it,” she said.

“Some lost their houses and never came back while people here still feel generally nervous given all the fires and smoke which are around right now.

“In 2019, as a brigade we were aware of the possibility of a fire happening but it’s not until it happens that the reality hits you.

‘Anecdotally we had been told by older residents that it had been 70 years since there had been a fire and you know the potential is there but then it happens, though were less shocked than some of the locals.

“Today there is much more co-ordination with council and emergency services and we learned a lot about setting up evacuation centres and getting that in place.”

‘STILL TRYING TO GET OVER IT’: FIRES STILL HAUNT VICTIMS

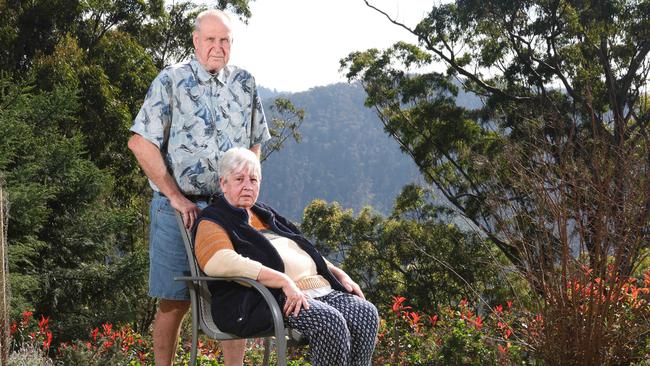

Pamela Skeen couldn’t leave her “piece of heaven” at Beechmont

Five years after she and her husband Stewart lost their home in the September 2019 bushfires, she still lives on the same property on Timbarra Drive in her rebuilt house.

Mrs Skeen loves the place but says the periodic back burning takes her straight back to the moment the couple fled their home.

“I’m still trying to get over it and they are backburning right know which doesn’t help,” she said.

“I keep trying to tell myself they are doing it to help us but it takes me back.

“I do love it here but it all takes time.”

The Skeens were watching television together inside their home of more than 25 years when they got a call from their neighbour warning of the raging inferno which was rapidly approaching their property.

The couple made it out of their house with the clothes on their back, a single family photo and their 15 pet birds.

Timbarra Drive was at the epicentre of the blaze with nine of the 11 homes destroyed in the bushfires on the one street. A tearful Mrs Skeen was embraced by then-prime minister Scott Morrison when he toured the ruins in the days after the fires.

While the Skeens and other rebuilt and resumed their lives, their emotional wounds still run deep half a decade later.

“I love this place, I fell in love with it because of the trees and how alive it was and to come back to it all being flatted just broke my heart, it really did,” she said.

“Rebuilding it wasn’t a hard decision, this was home for me and I wouldn’t go anywhere else, this is my piece of heaven.

“I still find myself looking for things which aren’t there anymore. I had all those CD before but they’re all gone now and you can’t seem to make it all up again. You can never entirely get back what you lost.

“We are getting back on our feet slowly, I love the house we have now and the gardens are all looking really good but the memories never really leave you.

“It’s taken a big toll on my health but I’m not too bad now.”

It’s the same story for Binna Burra boss Steve Noakes whose feelings of “deep sorrow” remain fresh.

“I get emotional even fight years on and certainly high winds and smoke aren’t a good sign and little things can trigger it,” he said.

“It was just devastating, it ripped my heart out to see the loss of something with some much heritage and history to it, something which so many people across the decades had been involved in

“It was a deep sorrow (but I just had) to just digest that and step into a leadership role and looking at the implicates for the staff and business

“It still feels fresh, like yesterday.”

Building contractors this week took control of the Binna Burra Lodge site for the long-awaited rebuild.

The project is expected to take 18 months to complete.

Mr Noakes said the resurrection of Binna Burra would finally be completed in 2026, seven years after the fires.

“The business reopened four years ago at a reduced scale and it will now take 18 months to rebuild the lodge, so by 2026 that recovery will finally be completed – seven years from the bushfires to our new normal.

“It shows that recovery from a disaster is not short-term, you have to have a big-picture vision, think long-term and stay the course.

“There’s plenty of times along the way you could just say it was too hard but staying the course is the key.”

ANALYSIS - HOW FAR CITY HAS COME SINCE 2019

I remember how afraid people felt five years ago, when bushfires knocked on the doors of homes in Lower Beechmont, a beautiful suburb in the northwest of my division.

And I remember how wonderful it was to see the community rally together during that difficult time, when the local QCWA delivered thousands of meals to frontline fireys and supporting volunteers, all prepared in their own kitchens.

I remember hearing how the Rural Fire Brigade shed was trying to manage both people afraid for their homes and loved ones while also facilitating the disaster response, with fire trucks coming and going.

After the event I listened and acted.

We sought and received support from the state government for our new Lower Beechmont Community Space, which will be completed in the coming month.

We sought and received support from the federal government to deliver an increased number of water tanks nearer the residential area, the wonderful murals for which will be a perpetual reminder to the community of the work invested into recovery and resilience.

We liaised closely with The Little Pocket Association whose work on community recovery and resilience through art has been profound and significant, helping with mental health and trauma within local hinterland neighbourhoods.

Community resilience after disasters is not just about building new buildings and infrastructure, even though that’s critical. It’s also about remembering the strength of character in the community and reminding locals of their capability when hard times strike.

As the Chair of the council committee overseeing disaster resilience, I’m proud of our work in Lower Beechmont, grateful for the contribution of community members and council officers who have worked together since, and I am hopeful that our efforts together have built a more resilient and better prepared community for the future, both for Lower Beechmont and throughout other parts of our city.

Cr Glenn Tozer is the Chair of the Lifestyle, Environment, Heritage and Resilience (LEHR) Committee and Councillor for Lower Beechmont.

LOOKING BACK: WHAT IT WAS LIKE INSIDE THE FIRE ZONE

The smell hits long before you actually arrive.

Nothing prepares you for what it’s like to enter a bushfire zone in the after aftermath of the blaze.

The acrid stench of smoke, burnt wood, melted plastic and metal is overpowering and unpleasant.

It was a Sunday morning in September 2019 when I, and other reporters, were sent into the Beechmont to tour the area alongside then-premier Annastacia Palaszczuk and then-police commissioner Katerina Carroll. They walked through the shattered remains of Binna Burra Lodge as well as along Timbarra Drive, where nine houses were lost.

The fires had passed but this rural residential street bore the scars of its impact.

The brittle metal skeleton of a two-stoery house, which only days earlier had been a much-loved home to a family, towered above the ash-covered ground, where singed garden pots and knick-knacks sat.

In a sign of just how ferocious the fire had been, metal had liquefied and been reduced to molten heaps. The destruction the fires had wrought that September proved to be only a precursor for the tragedy and destruction which hit other states just a handful of months later in what became known as “Black Summer”.

The Gold Coast was thankfully spared the worst which those states faced but the destruction came hard and early that spring.

It delivered a blow to the Hinterland and its economy just months before Covid arrived on our shores.

The houses have been rebuilt and the economy has bounced back but those who were impacted on those dark September days will never forget it.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Sharks unveil huge new stadium, $500m mega development

Southport Sharks has unveiled plans for a near-21,000-seat stadium and three residential towers in a massive redevelopment that could reshape the Gold Coast's sporting landscape.

Revealed: All Coast’s options for solving gridlock nightmare

The Gold Coast's population will surge by 350,000 in two decades, but the city's transport blueprint remains in limbo after light rail's dramatic cancellation. FIND OUT MORE