Stop the long-term pain from the Reserve Bank’s high interest rate assault | Paul Starick

Lured into large loans with the promise of low interest rates, householders and businesses need immediate relief, Paul Starick writes.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One of the more memorable stories I’ve covered was the closure of a 104-year-old family furniture business at Woodville Park, more than 26 years ago.

The demise of S. Lindsay and Co was not a huge news story. Five jobs, rather than lives, were lost when the Kilkenny Rd shop closed on November 28, 1997.

But, like Tuesday’s collapse of iconic vacuums retailer Godfreys, the loss of a longstanding family-run business hammered home the human cost of economic change.

Decades of enterprise, effort and enthusiasm were suddenly drained in both cases. Unique parts of the state’s identity and fabric were lost.

The long-ago tale of S. Lindsay and Co was an Advertiser front-page story on October 31, 1997.

The joint business owner, Ian Morgan, blamed the firm’s collapse on the introduction of pokies in July, 1994, after which the store’s earnings had slumped by 15 per cent.

But the business was already struggling after the loss of thousands of workers from nearby factory and foundry closures, plus cheap imports and the increasing dominance of large chains.

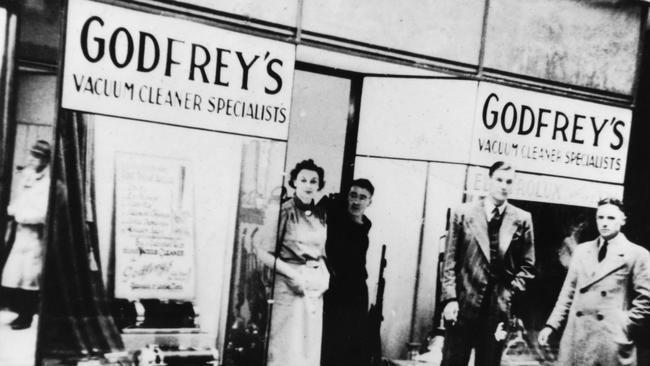

Godfreys, which was founded in 1931, has a proud history in SA – an Adelaide Arcade store opened in 1939, then reopened in 2018 by business co-founder John Johnson shortly before his death, aged 100.

His daughter, Jane Allen, said Godfreys, like many retailers, had been “heavily impacted by consumer confidence and spending due to the economic era of high inflation, rising interest rates, and intense cost of living pressures”.

Both businesses collapsed at key turning points in the economic cycle.

When the Woodville Park furniture store went bust, SA’s unemployment rate was 9.3 per cent.

It had topped 10 per cent for much of the 1990s but had just started to wane.

The road out of the early 1990s recession was gradual. Three years later, in October, 2000, unemployment was 7.2 per cent – five years after that, in October, 2005, it was 4.8 per cent.

Godfrey’s demise on Tuesday came the day before inflation figures heralded the end of the high inflation era and interest rate rises.

As a Moody’s Analytics economic note said on Wednesday: “Dead, buried, cremated: the prospect of another interest rate hike in Australia is no more. The odds of a hike were low leading into the December inflation print, but the latest inflation data confirm the Reserve Bank of Australia’s next move will be down.”

But an interest-rate cut cannot come quickly enough for households and businesses hammered by the 13 interest rate hikes that started in May, 2022 – little more than a year after Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe infamously signalled they would remain at historic lows until “at least 2024”.

December was disastrous for retailers. Rather than enjoying a Christmas windfall, retail turnover sank by 2.7 per cent nationally and 2.9 per cent in SA.

Roy Morgan research released on Tuesday shows 19.8 per cent of mortgage holders, or 964,000 nationally, were considered extremely at risk – significantly above the ten-year average of 14.2 per cent.

Australian consumers have a deeply entrenched pessimism that shows no signs of lifting, according to Westpac Economics research released on Thursday.

“Cost-of-living pressures continue to dominate, weighing heavily on family finances and buyer sentiment,” Westpac said.

The dial would be shifted only by meaningful improvements in interest rates and inflation – a combination unlikely until mid-2024 at best.

“Even with lower inflation and policy easing the real purchasing power of household incomes will take several years to regain lost ground. Living costs may stabilise but they will still be high relative to incomes. … In short, the consumer stagnation we are seeing now still has some way to run and the path out could be a long and difficult one,” Westpac said.

Households and businesses have been brought to a standstill by rate hikes.

The huge, consequential challenge for the Reserve Bank is to manage the cutting of rates more effectively than the hiking.

The deep risk is that people have been hit so hard, so quickly, that many will not be able to recover – like Godfreys and S. Lindsay and Co.

More Coverage

Originally published as Stop the long-term pain from the Reserve Bank’s high interest rate assault | Paul Starick