Why many Queenslanders can no longer afford to eat healthily

Chocolate used to be a treat but for many they are turning to the snack due to other reasons.

Eating healthily is becoming increasingly impossible for cash-strapped families, with the price of nutritious food rising at double the rate of junk food as groceries make up a whopping 37.7 per cent of the income in some households.

New Queensland research shows the price difference between healthy and unhealthy food as at its highest since 2019, with the Australian Dietary Guidelines “recommended diet” of meat, fish, vegetables, fruit, eggs, legumes, dairy and whole grains for a family of two adults and two children rising by almost 18 per cent from 2019-22.

At the same time, an unhealthy “habitual diet” of less fruit, veg and lean meats, and more highly processed foods such as chocolate, soft drinks, ice cream, chips, cakes, biscuits, takeaway and alcohol had increased at just 9 per cent in the same three years.

The research from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the University of Queensland shows how important it for families to have access to healthy food to prevent disease, co-author of the UQ findings, Amanda Lee, said.

“If we are looking at food security and to reduce diet-related disease in Australia, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers, it is really important that all people have access to healthy food,” she said.

The soaring prices are now making a healthy diet completely unattainable for those dependent on welfare, with food costing an incredible 37.7 per cent of their household income.

While those on minimum wage are experiencing “food stress” and are vulnerable to food insecurity as 26.4 per cent of their income goes towards feeding themselves.

With a household that spends more than 25 per cent of its income on food considered vulnerable to food insecurity, even families on the median Australian income are coming dangerously close to unsustainable levels, forking out 23.2 per cent of their earnings in 2022 on food.

Recording some of the biggest jumps in prices from 2019 to 2022 were vegetables and legumes, up 20.5 per cent, fruit up 23.4 per cent; healthy fats and oils (+27.3 per cent) and lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs and plant-based alternatives up 16.9 per cent.

Queensland Council of Social Service chief executive Aimee McVeigh said the dramatic escalations were “really concerning”.

“The exact same basket of groceries has increased by $80 a week [from 2022-2023] and with households already struggling and pushed to the limit, that’s an increase that they just can’t absorb,” she said, with the price rises being blamed on myriad issues including impacts of climate change, extreme weather events, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a reduced workforce, and increased costs of fuel, feed and fertiliser.

Ms McVeigh said many families were choosing their meals based on what they could afford, not what was healthy or, even worse, having to choose between paying rent or buying food. For those who choose rent, it can often mean relying on food relief services for their meals, like Foodbank Queensland, which currently feeds 150,000 Queenslanders, plus 28,000 school children per week.

“Food relief services offer low or no cost, but it’s not always the case that they can provide the best healthy food options,” said Ms McVeigh, with Foodbank revealing nutritious food like milk, dairy, meat and protein is always desperately needed.

With more than two-thirds of Australian adults and one in four children aged two-17 already overweight or obese, having more Aussies turn to unhealthy diets because of cost-of-living pressures is extremely concerning to chief executive officer of Health and Wellbeing Queensland, Dr Robyn Littlewood.

“What keeps me up at night is the future we are leaving for the next generation of Queenslanders,” she said.

“Research commissioned by Health and Wellbeing Queensland shows that if we don’t cut the rate of childhood obesity in half, children born this decade will live 4.1 years less than their parents. First Nations children could lose up to 5.1 years.

“We need government, industry and community to come together to address this crisis.”

Dr Littlewood said research showed that obesity, and its many related chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers, would cost the Australian community an estimated $87.7b by 2032; but Ms McVeigh said the problems of an increasingly poor diet were already being felt.

She said there were 200,000 children living in poverty in Queensland, unable to access healthy meals, which was leading to incredible social and behavioural problems among our youth.

“If you’re a child living in poverty your experience is of hunger, not being able to concentrate, particularly in school, of mood and behavioural issues, so it’s affecting your quality of life,” said Ms McVeigh, alluding to Queensland’s growing problem with youth crime.

“There’s lots of social outcomes that happen when children aren’t engaged with education and poverty is a root cause of so much problematic behaviour.”

Ms McVeigh said the state government needed to do more to support these vulnerable children and their families, and ensure that everyone could afford or have access to healthy, nutritious food.

‘LESS OF WHAT WE SHOULD BE EATING’

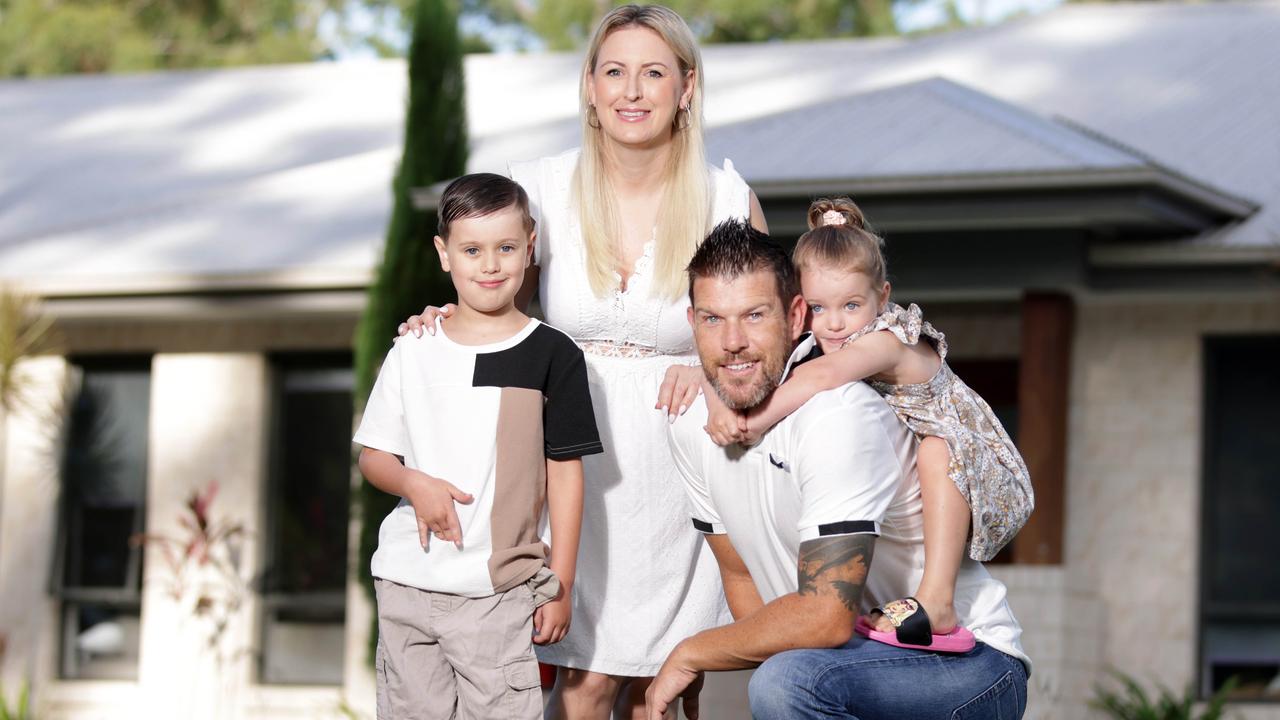

Logan Village resident Nikki Fielding says trying to keep her family eating healthy has only become more difficult with the cost-of-living crisis.

“Everyone in our house sort of eats a little bit differently. So I have to buy different foods. So yeah, I do notice (the price) a lot because the kids eat a lot of fruit,” Mrs Fielding said.

“But I’ve more or less said no to buying a lot of stuff because of the price of it. Like my son will only eat certain types of fruit. But at the moment he’s down to apples. The other ones that he eats are just getting a bit too expensive for me.

“I like to eat a lot of veggies and I make a lot of salads, but the kids won’t eat a lot of that. So they eat more fruit on those nights when I’m eating salad.

“I guess like pumpkin and potato stuff (because it is cheaper). Not so much eat greens any more.

“Yeah, bulking out with other things and eating less of the ones we probably should be eating.”

Mrs Fielding also found that the quality of fruit and vegetables had vastly declined.

“When I buy it, it actually doesn’t even last that long either. Which is also a big problem,” Mrs Fielding said.

“So while they’re charging a lot for it, it expires quite quickly. So we’re actually buying twice, shopping twice a week for fresh fruit and veg.

“If you’re happy to buy the same vegetables, you buy that in bulk and cook two meals a week and everybody just eats that then great for your household. You can have a cheap bill. But if you’ve got people with different requirements, or only even just in health in general. That makes it difficult and far more expensive.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Why many Queenslanders can no longer afford to eat healthily