High Steaks: Indigenous Policy Evaluation Commissioner Selwyn Button

You may not know his name, but Selwyn Button’s journey from a childhood playing footy in Cherbourg to the halls of Harvard University is fascinating and inspires his next role helping Indigenous Australians. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

How on earth do you transport yourself from Cherbourg in the South Burnett to Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts?

It’s not a complex matter if you view the journey in purely practical terms and have enough cash to pay airfares for the 16,000km trip.

But Selwyn Button, whose Gungarri people are from the Maranoa River region, did far more than fly across the Pacific Ocean and continental America to arrive at Harvard Square.

This still youthful looking Indigenous Australian who turned 50 two weeks ago has crossed more hurdles than most to make an extraordinary success of his life, yet remains one of the more enigmatic figures in Australian Indigenous politics.

Becoming a Wolfensohn Scholar at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government is perhaps his most stunning accomplishment, taking him from his rugby league playing days in Cherbourg to America’s Ivy League.

“I do see it as a significant achievement,’’ he says. “But in some ways, I think it was a sort of recognition of the things that I did before I got the scholarship.’’

Those “things I did’’ are truly extraordinary.

Selwyn, who played a low-profile but key role in the Voice referendum of 2023, has been, among other things, a primary school teacher, a police officer, Queensland’s Assistant Director General of Indigenous Education, CEO of the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Registrar of Indigenous Corporations, Chair of Lowitja Institute and Queensland Rugby Union Board Director.

A fortnight ago, he was appointed a commissioner with the Australian Sports Commission and in June last year he was appointed the Productivity Commission’s Indigenous Policy Evaluation Commissioner in a term lasting five years.

It’s from that vantage point that he intends to help guide Australia’s Indigenous population onto those pathways of prosperity that have for too long eluded them.

Sitting at the Crown Hotel in Lutwyche in Brisbane’s inner north, dining on fillet steaks and salads, he readily admits his glittering future was not evident as he and his mates played footy and wandered the streets of Cherbourg and the nearby town of Murgon, 250km northwest of Brisbane, in the 1980s.

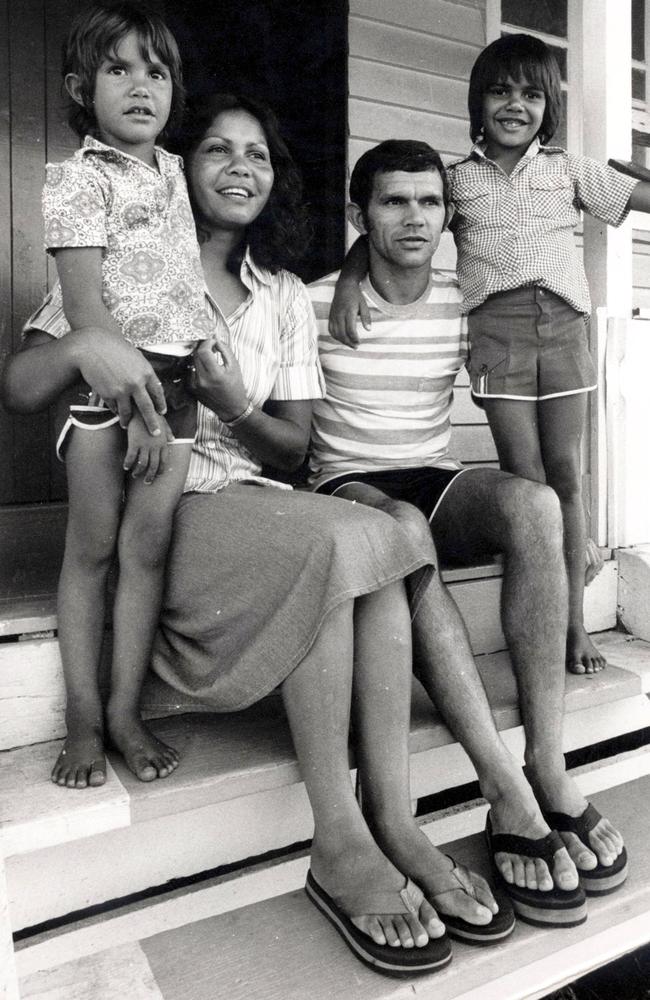

He recalls a dad and mum not being overly strict in their approach to parenting, but more than ready to come down hard on him when he did the wrong thing.

”I grew up in an environment where I knew what was right and what was wrong and I knew what was expected of me,’’ he recalls.

Inspired by his teachers in primary school, he first attended Griffith University to become a teacher before joining the police force and then moving into executive areas of the state public service, all before he had reached the age of 30.

While working in the Queensland Education Department he embarked on a project instrumental in, quite literally, “closing the gap’’ between indigenous and white high school students in Year 12.

He realised that many teachers needed some guidance in reaching not only Indigenous kids, but the families of Indigenous kids.

“It was an interesting conundrum – the teachers knew the kids were there, but it was just about getting a better understanding of what their needs were,” he says.

“So it was about talking to principals about building better relationships.’’

The program was an outstanding success, putting Indigenous students almost on par with white kids in the classroom.

The OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) started writing about his efforts and giving international exposure to his ideas, and he was on his way.

Open to senior public servants across the nation, the Harvard scholarship – named after Sir James Wolfensohn, the Sydney-based lawyer and economist who was World Bank Group president from 1995 to 2005 – only further cemented Selwyn’s presence among influential figures in the global community.

“Some of the real value of doing something like that is making contacts with people who are experts in all sorts of fields,” he says.

His vast knowledge and experience is now being directed, via his work with the Productivity Commission, into finding ways to assist Indigenous Australia to get its fair share of the nation’s wealth. Indigenous land ownership is one area which interests him.

Recognition of native title, crystallised in the public mind with the 1992 High Court Mabo decision, is now so common many Australians believe vast tracts of the nation are under Indigenous control. But it’s not that simple.

The land may generate money via, among other things, mining royalties, but that money does not always reach individuals.

“The majority of that money is wrapped up in charitable trusts,’’ Selwyn says.

If an individual in an Indigenous community wanted to start a small business, it’s by no means a given that they could access the wealth accumulated in trust funds.

“That might break the rules of the trust,” Selwyn says. “There is significant amount of money sitting in accounts, but they are restricted in how they can spend the money.’’

He will work with the Productivity Commission in providing advice to governments on how better to put the money to work to bring financial independence to Indigenous people.

Indigenous home ownership is another area in which he wants to see progress.

Home ownership in indigenous communities is lawful, championed by Federal Member for Kennedy Bob Katter for so long (and so loudly) that present land title arrangements in communities are known as “Katter Leases”.

But a more solid freehold title, as it exists in mainstream communities, may be on the agenda in the years ahead, even if there is a pushback from sections of the Indigenous community who still believe in a collectivist approach to land ownership.

As for that perennial issue impacting on Indigenous Australia – Australia Day itself – Selwyn believes we might be better off commemorating our birth in January 1901 when Australia became a federated nation. But he acknowledges, with a smile, that such a date will generate widespread protests, and not necessarily from the Indigenous community.

A Federation Day proposal is guaranteed to enrage the average Australian punter, who will point out that January 1 is already a holiday.

The annual street protests of January 26 are, in his view, reflective of a dynamic that has remained a constant in Australian life since the First Fleet’s arrival in 1788.

He is clearly fascinated by (and well-versed in) early Australian history and sees the ongoing currents of Indigenous/European interactions as originating in the first few years following 1788.

It was in that period that two key figures emerged among the Indigenous inhabitants.

One was Bennelong, the first Indigenous person to engage in real dialogue with the British leaders, including Governor Arthur Phillip, who oversaw the establishment of the colony. The other was Pemulwuy who headed a guerrilla campaign to drive them out.

“Those varying approaches have always been there, we just haven’t noticed them,’ Selwyn says.

“It’s a matter of push and pull. Do you need the Bennelong approach or do you need the Pemulwuy approach?’’

Ultimately, he believes, it comes down to a compromise. Protest is sometimes required, just as dialogue can prove the most productive path forward.

“You need to work out what’s the middle ground, so you can be sure you are getting your point across, and you are achieving the changes you want,” he says.

How the Voice campaign (which he vigorously supported) reflected that ongoing dynamic, we’re both not entirely sure. Regardless, the Voice is now behind us and Selwyn is more interested in shaping the future.

He’s probably more naturally inclined to the Bennelong approach in all his dealings, but he does note an uncomfortable reality.

Over the past two centuries, neither of these political philosophies – war or diplomacy – has produced the result he wants.

And what he wants is Indigenous Australia getting a fair share of the wealth generated by this prosperous, first-world nation over the past 250 years.

Meal finished, the happily married grandfather of two is off to another engagement and, as we both agree, the Crown Hotel rarely fails in providing a superb lunch. Nine out of ten.

Originally published as High Steaks: Indigenous Policy Evaluation Commissioner Selwyn Button