Parents of baby who died needing a heart transplant urge support for organ donation

A new heart was Remy’s only chance at life after he was born with a severe genetic condition. The brave boy tragically died before his first birthday, sparking his parents to take action for an important cause.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A heart transplant for their beautiful baby, Remy, was the “light at the end of the tunnel” that never came for Melissa Lei and Joseph Shomali.

Little Remy was born with a genetic cardiac condition and a new heart was his only chance at life.

Tragically, the smiley, brave boy who took so much hardship in his stride suffered three strokes after a few months on the transplant waitlist. Remy died at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital in October. He was 10 months old.

His Canberra-based parents are telling their story to spread awareness about the importance of organ donation, as new figures reveal an annual decline in lifesaving transplants and family consent to donation in Australia.

Just 53 per cent of Australian families said ‘yes’ to donation last year, down from 55 per cent in 2023 and 60 per cent pre-Covid.

Remy’s parents also want their son’s short life to leave a positive legacy.

“It’s a way that we can keep him alive,” Melissa said.

“He still led a beautiful life that he fought for. It’s not the ending we wanted, but there’s so much value in the short amount of time he had. We feel so incredibly proud of him.”

RELATED: Behind the scenes of the lifesaving organ donation process

Twelve days after Remy was born, his parents feared something was wrong when he wouldn’t wake to feed. Remy’s severe diagnosis set him on a traumatic journey that involved long hospital stays, endless medical procedures, breathing support, feeding through a tube and three open-heart surgeries to have a ventricular assist device (VAD) implanted to pump blood from his heart to the rest of his body.

The family spent months at a time in hospitals across Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne.

The couple was in awe of how their baby boy adapted to being constantly poked and prodded.

“He was a calm baby from the get-go – it felt like he was taking care of us,” Melissa said. “Despite everything that happened to him, he retained the ability to smile and be happy. He was a beacon that never dimmed.”

Joseph added: “It was a beautiful, brutal time in our lives. It was a traumatising time, but equally, it was magical.

“We used to play music and dance (in hospital), and you could see him trying to squirm his little legs.

“We were a happy family, despite everything.”

The family got two and a half precious months at home in Canberra last February before Remy landed back in hospital. He spent the next five months at the Royal Children’s on the VAD waiting for a suitable donor.

Being told their son needed the VAD was “more devastating than hearing that he needed a transplant”, Melissa said, as it opened him up to profound risks like blood clots and strokes.

Her partner added: “A transplant gave us a light at the end of the tunnel. We saw a life where we could take him home and be together as a family.”

Remy bounced back from a severe stroke in early September. But a second major stroke a few weeks later meant a transplant was no longer viable.

Joseph said he was startled to learn how few people became donors in Australia each year.

In 2024, 1328 people received lifesaving transplants (down 5 per cent annually) from 527 deceased donors (up 3 per cent), according to the latest Australian Donation and Transplantation Activity Report.

Organ and Tissue Authority chief executive Lucinda Barry said these numbers reflected the fact more people were getting the opportunity to save lives as donors, including older Australians aged into their 80s – a “really encouraging” outcome. But they typically could not donate as many working organs as younger donors, resulting in the slight drop in transplants.

One organ donor can save the lives of up to seven people.

Less than 2 per cent of Australians die in hospital in circumstances where donation is possible, and families are asked to consent regardless of whether their loved one is registered to become a donor.

Ms Barry said the decline in people agreeing to donate was a concerning trend that was being reflected globally. A return to 60 per cent would mean an extra 175 lifesaving transplants per year.

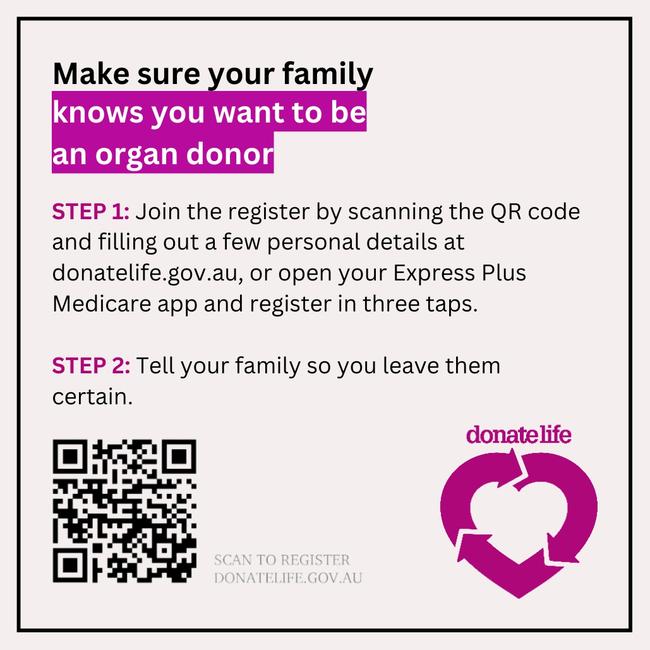

The OTA was striving to achieve this by encouraging all Australians aged 16-plus to register via donatelife.gov.au or the Medicare app, and ensuring that more than 90 per cent of families asked to consent to donation were supported by a specialist nurse.

Four in five families consented to donation when their loved one was registered in 2024, and three in five agreed when a specialist nurse was present.

South Australia – the only jurisdiction where residents can pledge to become donors by ticking a box on a driver’s licence application or renewal – retained the nation’s highest registration percentage at 74 per cent. The Northern Territory (15 per cent) and Victoria (23 per cent) had the lowest.

Losing Remy has made his parents staunch advocates for organ donation. They hope their story will inspire Australians who haven’t registered to do so, and then tell their families of their wish to become a donor.

It only takes one minute to register at donatelife.gov.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Parents of baby who died needing a heart transplant urge support for organ donation