Englishman’s longing for home led to Australia’s rabbit infestation

Englishman Thomas Austin hoped to make his block of Australian wilderness more like his homeland when he released 12 breeding pairs of rabbits onto his sprawling estate near Geelong. What he’d really unleashed was an ecological disaster.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In October 1859, Geelong settler Thomas Austin was very excited. He was about to let something loose on the landscape.

The Englishman was determined to make his huge block of Australian wilderness more like his homeland of Somerset.

A member of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, Austin was part of a group of British colonists who brought plants and animals from Europe to the colonies to make the unfamiliar landscape more comfortable.

His expanding garden was already host to English trees, many of which struggled in the Australian climate.

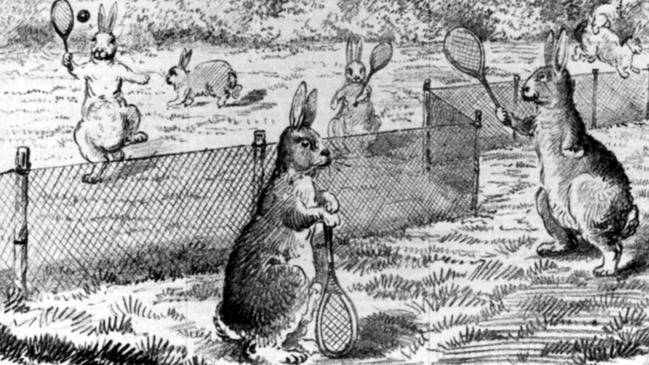

Now he had a plan to establish a hunting ground, just like gentlemen enjoyed back home.

FAIR GAME

As Austin opened a cage, 12 breeding pairs of European rabbits bounded out to the shrubs and grasses around the sprawling estate near Winchelsea.

In the following years, Austin discovered his plan had worked.

There were plenty of rabbits to hunt. When the Duke of Edinburgh visited in the 1860s, a hunting expedition saw hundreds of rabbits shot.

There seemed no end to them.

And there really was no end.

Austin didn’t realise the rabbits were reproducing at an exponential rate and spreading rapidly across the continent.

Each female was producing 30 more rabbits each year. Soon the horde was racing north and west at more than 100km every 12 months.

Before long there were millions of rabbits. Then, astonishingly, there were billions.

Austin’s misguided attempt to make an English hunting ground near Geelong became the pre-eminent ecological disaster in Australia.

The whole young country faced a crisis that called for continent-wide action.

RABBIT PROOF FENCES

Thomas Austin was not the first to bring rabbits to Australia.

Some had come with the First Fleet in 1788 and although a small number were released into the wild, rapid reproduction on the mainland did not become a problem until Austin’s release in Geelong.

Earlier in the 1820s rabbits were already in the wild in Tasmania.

It is believed a blending of breeds might have meant Austin’s rabbits were more suited to the Australian climate and conditions.

The rabbits’ appetite for low shrubs and unstoppable burrow digging wreaked havoc.

By the end of the Nineteenth Century, acclimatisation was abandoned and the New South Wales government offered a huge £25,000 reward to anyone who could find a way to eradicate the rabbits.

In the early Twentieth Century, the newly federated Australia tried a new innovation to stop the rabbit spread.

An ambitious project to build a fence running north and south across the whole Australian continent was undertaken.

Between 1901 and 1907 more than 3200km of wire fencing in three sections was erected across Western Australia, with the wire extending below ground to stop burrowing.

Similar fences were proposed in the east to stop rabbits moving north.

For decades the western fence was inspected and maintained by workers in buggies drawn by camels.

Despite the efforts to build and rebuild the fences, and the continuous trapping and hunting of rabbits, their numbers kept growing.

By the 1920s there were believed to be an astonishing 10 billion rabbits in Australia.

The destruction to habitat and agriculture was incalculable.

THE VIRUSES

In 1950, Australian scientists were very excited. They were about to let something loose on the landscape.

Since 1937 a trial program on Wardang Island off South Australia had been refining a virus that only affected rabbits.

And it affected them badly. Highly contagious and brutally lethal, the myxomatosis virus was the new hope for eradicating the pests.

After the first infected rabbits were released in 1950, the virus swept the country with an even greater swiftness than the rabbits.

The initial death rate was more than 99 per cent. Hundreds of millions of rabbits were killed within a few years.

Farmers watched in awe at the effectiveness of the virus, which caused panic among some communities that the virus could jump from rabbits to humans and wipe out the population. But it never did.

Although the majority of rabbits were killed, a small number were unaffected and developed immunity, leading to a resurgence.

In the 1990s the CSIRO began work on the calicivirus which, after years of testing, was released with great effect.

Despite the effects of the viruses and other mitigation, there is still estimated to be more than 200 million European rabbits on the Australian mainland.

That’s eight times more rabbits than people.

Thomas Austin died before he could see the full horrific effect of his rabbit experiment.

He and his wife, like rabbits themselves, had 11 children.

After the Duke of Edinburgh’s visit, Austin was embarrassed by his modest homestead and set to work building something grander.

His bluestone mansion at Barwon Park, built in 1871, still stands. Austin died a few years after its completion.

In the grounds and garden surrounding the house, the descendants of Austin’s two dozen rabbits can still be seen in the wild.

MORE MITCH TOY

LARGEST GOLD NUGGETS UNEARTHED

Originally published as Englishman’s longing for home led to Australia’s rabbit infestation