Peter Baruch reveals extraordinary story of how he escaped the Nazi as a young boy

Peter Baruch was just one when Nazis came to his home town. His parents faced an agonising choice. This is the extraordinary story of how they saved him from the ghetto.

Gold Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Gold Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“When you survive something like that, you keep on surviving.”

Peter Baruch smiles.

He smiles a lot. History has delivered him to a place of dreams. A Gold Coast unit, comfortable leather armchair, warm breeze, views worthy of a great artist’s brush.

Walls and shelves are adorned with photos. Of his five children and seven grandchildren – “My family is very important to me.”

It’s testament to a miracle life. An unlikely life, one hewed from the shortest of odds. A life only a minuscule few of his kith and kin got to lead.

Peter Baruch was born on July 23, 1938, in the city of Lodz in Poland.

To a family of Jews.

A LIFE OR DEATH DECISION

Peter Baruch has a blanket.

A blanket that he one day plans to leave to the Holocaust Museum in Brisbane. A blanket that was made in his grandfather’s textile factory in Lodz.

“Lodz was an industrial city. Before the war it had around 700,000 people, of which about 230,000 were Jewish,” he says.

“Textiles was the main industry, and most of the population, including my family, were involved in some way.

“My grandfather had a factory. His father was one of the first to open a textile factory in Lodz back in the nineteenth century. So the family for generations has been living in Lodz.”

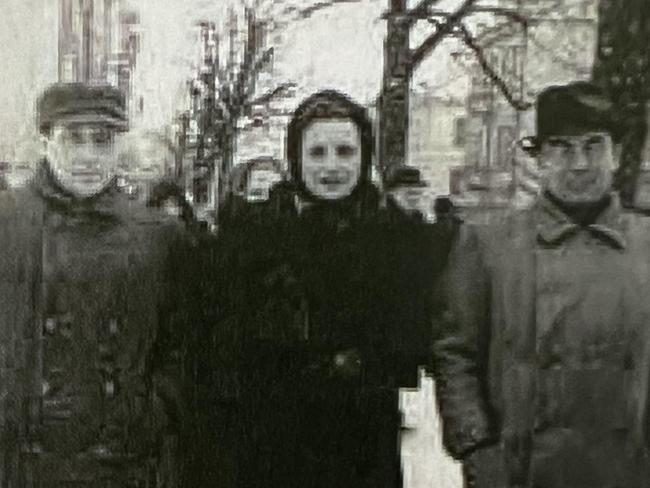

It was a big family. Peter’s father Klemens had seven brothers, his mother Marysia two. He had many cousins.

They were well off. They owned a country estate, Baruchovka, where they would holiday together. They had servants, nice cars. A good life.

Then came September 7, 1939. The day the Nazis rolled into town, less than a week after first crossing the border into Poland.

“My family met, the whole lot of them, and decided whether we should stay or whether we should go,” Peter says.

“The general consensus was we should stay. After all we had lived there for generations, we had businesses, we had homes, we had good friends.

“ … This was fairly common among most Jews in Poland. Why leave? The war won’t last that long, and everything will return to the way it was after the First World War, which was fine.

“For some reason, my parents said that they were going.”

Just weeks after the Nazis had arrived, in the dead of night, Peter’s parents slipped away, their Fiat car laden with whatever food and valuables they could bring with them.

“My mother had some beautiful jewellery and she sewed it into the hems of her dresses,” Peter says.

“We couldn’t get any money because all Jewish bank accounts had been closed by the Nazis.

“But my father had managed to get some Russian roubles and American dollars. She sewed those into the linings of coats.”

The most precious cargo: their one-year-old son, Peter, wrapped against the winter cold in the blanket he has kept with him to this day.

“She wrapped me in that rug that you saw to keep me warm,” he says.

HOPE OF ESCAPE

With the family in that small Fiat car was Peter’s uncle Jusio.

Jusio had worked in Japan, representing family companies. He had heard there was a Japanese vice consul just over the border in Kaunus, Lithuania, giving transit visas to Japan to Polish Jews desperate to escape.

The diplomat’s name was Chiune Sugihara.

“Sugihara gave us the transit visas for Japan. They enabled us to go through Japan but we were unable to stay there,” Peter says.

“But he thought at least this would give Polish Jews an opportunity to get out of Europe.

“His government wouldn’t respond to his requests but he went ahead and did it (without the permission of his superiors) in the middle of 1940 and saved the lives of 6000 Polish Jewish refugees.

“Not many are alive today but children, grandchildren, great grandchildren throughout the world total about 200,000.”

Sadly, despite getting a visa, Peter’s uncle Jusio was not one of them.

“My uncle said he was going back to Lodz to get his girlfriend because he’d obtained a transit visa for her as well. We never saw him again,” Peter says.

“We learned after the war he made it back to Lodz. He had been denounced as Jewish by a Polish neighbour. The Nazi soldiers came for him, he tried to run away, and he was shot in the back and killed.

“He was 25 years old.”

With the exception of one other surviving brother, Peter’s parents were never to see any others from their family again, either.

“(Apart from that one brother), they all perished in the Lodz ghetto and the concentration camps.”

A PERILOUS JOURNEY

Peter’s parents hoped they might wait out the war in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. But the arrival of the Nazis at the border made clear that with no resources bar the values sewn into clothes, they would have to somehow make the perilous trip to Japan.

The only possible route – through communist Russia.

“We managed to get Russian exit visas which enabled us to get into Russia. But we could only stay there for a short time or we’d have to move on. If we couldn’t move on they’d send us to Siberia, to the gulags,” Peter says.

“So we made it through to Misnk. At Minsk we were met by a Russian patrol and they confiscated our car, helped themselves to anything of value. Fortunately they didn’t find my mother’s jewellery.”

The family found their way onto a rickety bus to Moscow, making the 250km journey under constant threat of strafing from Nazi war planes.

There they were helped by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (Joint), a relief agency that found them shelter and food.

But they could not stay long.

“We had to get tickets for the trans Siberian railway. A journey that was going to take us 12 days. But we didn’t have the money,” Peter says.

“My mother managed to sell her jewellery. And with that money, and a bit of assistance from Joint, we were able to get third class tickets on the train.

“It was full of refugees. Unbearably hot inside, freezing outside.

“We slept on wooden benches. There was very little to eat.”

Near starving, refugees on the train bartered with locals whatever valuables they had left – “a beautiful diamond, or a magnificent brooch or necklace” – for food for one day.

Eventually they made it the eastern Russian port of Vladivostok, where they were again met by the Russian army, who went through their belongings and helped themselves to anything of value they could find.

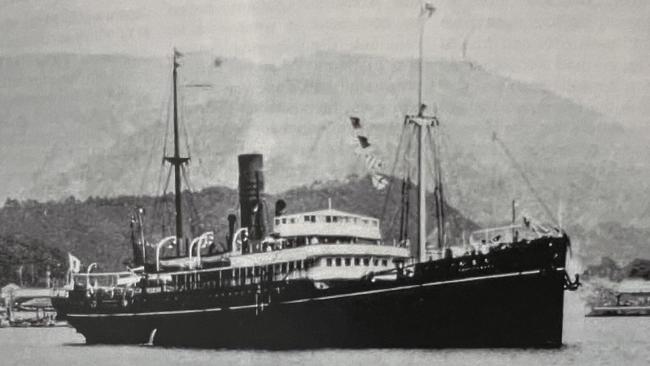

Joint then got them tickets on a ship across rough seas to the port of Tsuruga.

The ship – the Amakusa Maru – was not meant for people. It was a cattle boat. They slept huddled on the hard wooden deck.

KICKED AND PUNCHED AS BYSTANDERS LAUGHED

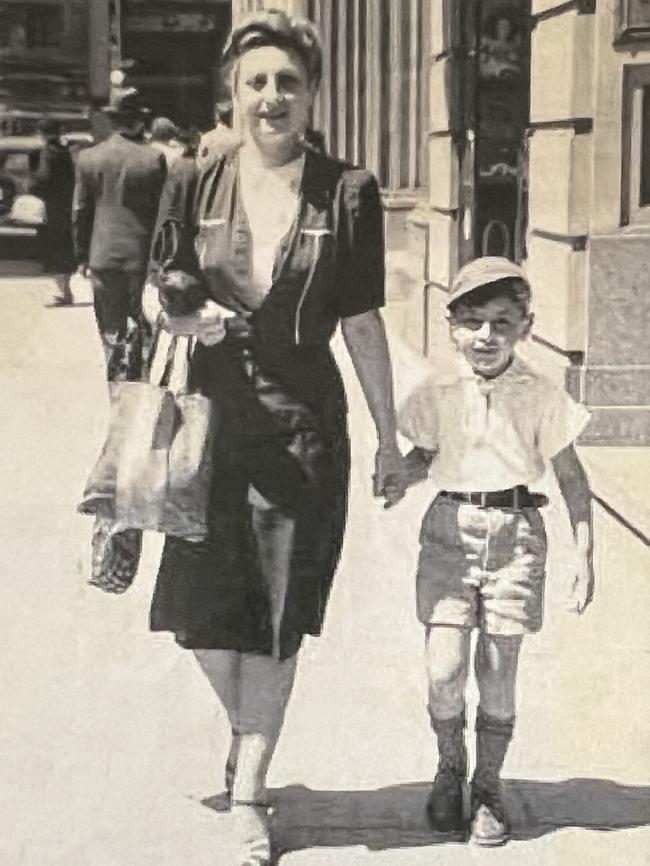

The family spent a number of months in Japan, settling in Kobe, with Peter spending his third birthday there.

But it was soon time to move again. Peter’s account of his family’s flight from Europe is not from memory, he was too young, but pieced together from the accounts of survivors. Japan, though, he remembers.

“One day I was out playing with some other refugee children and some other Japanese boys joined us. And they started hitting us.

“I was the youngest and the smallest and the slowest. They caught me and they threw me on the ground. They kicked me and they punched me.

“And I can recall looking up and seeing Japanese adults standing there watching. Many of them were laughing. Some were clapping.

“Attitudes in Japan were very quickly changing because Japan was about to enter the war.”

Peter’s family were told they needed to go. The United States said they would take 500 of the 4000 refugees in Kobe. Peter’s family did not make the list.

With London under Nazi bombardment from the air, the British said they could not take them.

However they suggested three “colonies” – Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Peter’s father somehow managed to get a visa for New Zealand. In August 1941, they were on their way again.

Via Indonesia and Sydney, they finally made their way to Wellington, landing on 28th October 1941.

It was a journey that had taken two years. And that barely anyone achieved.

While about 1100 Jewish refugees were accepted into New Zealand between 1933 and 1947 – itself a desperately small number – during the war years, such arrivals almost completely ceased.

“The total intake of refugees for New Zealand was 15 people. There were basically three families and some single men,” he says. “At that time 15 people.

“Fortunately New Zealand was very kind to us. I grew up there, went to school and university there. My four older children were all born there. My parents are buried there.

“In 1990 I made a decision to move to Australia and we settled here on the Gold Coast where I live very happily today.

“And it was all because of this one man, Chiune Sugihara.”

A TERRIFYING WARNING

Peter is now retired. But in many ways, has never been busier.

As we speak, his phone rings. It’s another group asking if he can come and give a talk about his family’s history, that perilous journey he made as a small child.

He consults a bulging diary. “Yes I can make it”. Another appointment lined up.

Most of his work is with Courage For Care, set up by Jewish service organisation B’nai B’rith to counter the dangers of racism, prejudice, discrimination and bullying.

“Basically we visit schools and talk to them about discrimination, intimidation, bullying, and how they can be upstanders – in other words stand up for other people – and not simply bystanders,” Peter says.

“They (schools) always want us to come back all the time.

“We’re fully booked for next year. I’m going to the Sunshine Coast again next week for three days and that’s the finish of this year.

“Next year I’ve got a very busy schedule from the time school starts until it finishes.”

Events of October 7 in Israel, when Hamas terrorists murdered more than 1400 innocent people, and kidnapped more than 200 more – “it was unfathomable, horrific, unbelievable”, he says – have made Peter’s mission to educate young people about the Holocaust seem more important than ever.

As has the deeply distressing sight of people chanting about killing Jews on Sydney streets.

“These people do not understand history,” he says. “These people have been brainwashed into hatred.”

A history that includes his story, of a family constantly moving, unwanted, reviled, fleeing for their lives simply because of their faith.

A story of survival against odds most of us can scarcely fathom.

Ultimately, it has finished for Peter with a comfortable life of safety on the Gold Coast. Only a very lucky few from 1939 Lodz would see their story end in such a way.

His tale is a warning from history, a terrifying dispatch from the near past about where hate and prejudice can lead.

One he is determined to tell to as many as possible – “As long as I’m able I’ll continue”, he says – and most especially to the young.

“My message to young people is to know your history, to learn from your history, to be an upstander and not merely a bystander and to do good in this world,” Peter says.

“Chiune Sugihara didn’t have to do what he did. He defied his government to do it. He took massive personal risks to do it. But he felt he had to do it.

“I’ve lived through a Holocaust. I don’t want to live through another one.”