Legendary Gold Coast horseracing identity Eddie “The Fireman” Birchley dies at age 86

EDDIE Birchley spent 17 years as a firefighter before abandoning it for a career as a punter, becoming a legendary figure in the 1970s. He is being remembered for his prowess after dying at age 86.

Gold Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Gold Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

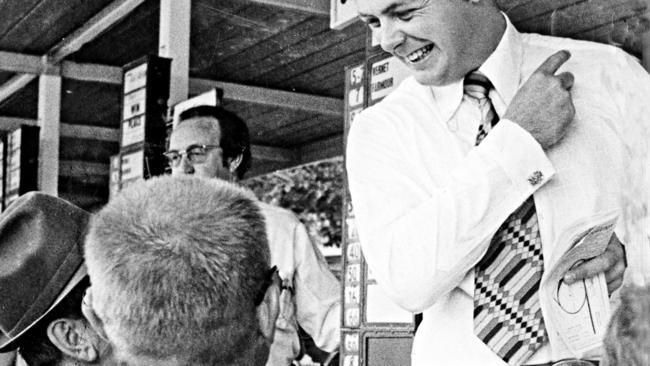

EDDIE “The Fireman” Birchley was one of the biggest punters of his time, plunging $100,000 on races in the mid-1970s when the average wage was $7500 a year.

As big a thrill as the chase was the media storm he created and Tweed local Barry Clugston — who knew “The Fireman” for more than 50 years — said he “would have loved” one last run in the newspapers, for the limelight, as much as to let people know he died on July 25, aged 86.

Birchley was known as “The Fireman” because before turning to punting he had been with the fire department for 17 years.

“I was a boxer in my youth,” he told a journalist in November 1974 following a “hit-and-run” dash from the Tweed to Rosehill where he pocketed $24,200 after putting $51,950 on 5-2-on favourite Debbie Jo.

“But these days I work out in the gymnasium at the Greenmount Life Saving Club. Every day I swim from Greenmount to Kirra with the local beach inspector.”

Birchley’s daughter, Leigh, said he was always a gambler and in his teens was running a book on the Brisbane wrestling scene.

“In the end, Brisbane bookmakers wouldn’t take him for enough money so he’d fly to Melbourne or Sydney for a particular race and might chuck $100,000 on — which was a lot of money in the ’70s.”

The Birchley legend is one of those stories that grows a little longer and a little better each time it is told.

Birchley’s first major win came from a risky property venture in Queensland that eventually paved the way for him to retire from firefighting and turn his efforts to horses and form guides.

He plunged the profits from that venture — $40,000 — on a sprinter named Tod Maid. It won

“I am not classified as a professional punter, it is merely a hobby,” he told media in 1974.

The week before his November 1974 Rosehill trip, at which he took on bookmakers such as Bill Waterhouse and Les Tidmarsh, he was said to have visited Warwick Farm to put $60,000 on St Louis Blue. It won.

Before that, he invested $200,000 on a horse named Caboul, an easy 6-1-on winner at Flemington.

He told a reporter he never got nervous before making big bets. “(But) I am feeling nervous for the first time today,” he said. “This publicity is bad for me. It will probably chase me out of racing.”

In the end, whether he jumped or was chased, Birchley did walk from the big-time punt and racing. He claimed bookies and some jockeys had conspired to have the horses he bet get beaten. No evidence was offered.

Clugston said he still fluttered, but never the sort of massive plunges for which he was famous.

“I think he enjoyed the thrill and banter of risk taking,” his daughter said. “Later, when he was in the (aged care) home the nurses rang me and said, ‘we’ve just got to tell you, we’ve found $14,000 in the seat of your father’s (walking) frame’. He’d been going down the club and betting on the football. He was still winning money, even as an old codger in the nursing home, he couldn’t help himself.”

One thing that couldn’t be argued was the mark Birchley left.

He is mentioned in books, including that of underworld figure Mark Brandon “Chopper” Read’s Chopper Unchopped.

“It happened one day at Moonee Valley,” Chopper wrote. “Me, Dave the Jew and Vincent Villeroy stood and watched Eddie “The Fireman” Birchley stick $50,000 on one horse — and win ... Dave the Jew wanted to kill Eddie Birchley, but me and Vincent wouldn’t allow it. Call us sentimental fools, if you like, but “The Fireman” was part of racing history ... It was a privilege just to watch him in action. His ilk are all gone now”.

Birchley saw out his time at the Opal Florence Tower specialist aged-care home in Tweed Heads.

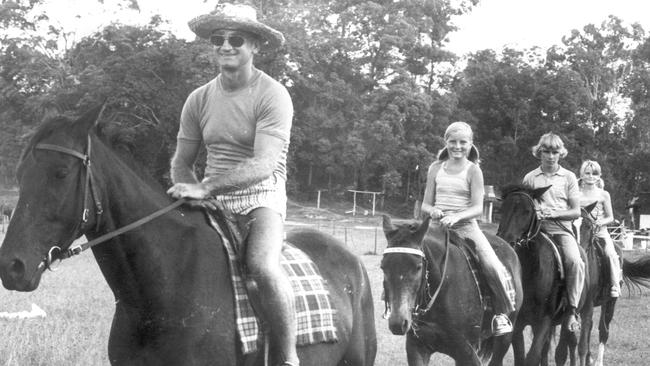

Clugston said as the years caught up with him, Birchley would ride his scooter to Jack Evans Boat Harbour to swim.

His daughter said the home called her about that too, saying he’d been swimming in the Tweed River and they worried he might be washed out to sea.

He loved the ocean and his family plan a private funeral where they will release his ashes in the sea. He is survived by his three children and two grandchildren.