From Palestine to the Gold Coast: Mum’s remarkable journey

A Gold Coast mother has revealed the lengths she went to in order to protect her children, which ultimately saw her flee to safety in Australia. This is her story.

Gold Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Gold Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A car is stopped just outside the Qalandiya Checkpoint between Ramallah and occupied East Jerusalem. Plumes of smoke erupt around vehicle, stones go flying past the window.

Suheir Zeidan wonders, not for the first time in her life, whether she’s going to lose her babies right then and there.

Israeli soldiers fire tear gas and stun grenades into the crowds that trap their car in the crossfire. Young boys dart out from under cover to hurl stones back.

Her husband Samer Gedeon is tense behind the wheel trying to get them safely past the chaos, but they’ve been in the car for so long her prematurely-born son begins to wail with hunger.

She gave birth so early that the breastmilk is still dry and there’s nothing she can do.

Suheir, worn ragged, cries too in the back of the car.

On that day in 2007, it takes them four hours to make the 25 minute drive from Qalandiya to their apartment in Jerusalem.

“It was a miserable time,” she recalls, sitting in the backyard of her Southport home. “It was a miserable life under occupation.”

“But we would do this every day, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to live and pay the rent.”

Every day the family risked harassment and even death to cross the military checkpoint into the West Bank where Suheir worked a well-paying job as a Palestinian public servant and where her children could visit family.

“I was terrified. It felt like we were committing a crime, like I was sneaking in and out of a foreign country,” she said.

The decide at some point to travel with their wedding photos in the hopes that it would convince the soldiers they were actually married.

“We thought maybe the Israeli soldiers would see them and feel something, feel sorry, and let us pass into Jerusalem,” she said.

“But there was no mercy. They’re indoctrinated to hate us, that Arabs are bad. And I was always so worried they would stop me and ask for my ID.

“Mine was green.”

A tale of two IDs

Suheir turns to her husband one day and nearly breaks both their hearts.

“I think we should separate,” she tells him. “This life can’t continue.”

Back in Southport today, Suheir sips her espresso and smiles a little ruefully thinking back on that moment almost 16 years ago.

“Don’t get me wrong, I loved my husband and he loved me. We didn’t want to separate at all,” she said.

“I remember he actually laughed at me saying ‘don’t say that’ but I was convinced.

“And at some point we started having these discussions, that our life can’t continue like this. I couldn’t keep commuting to Ramallah. And my husband was stuck in Jerusalem because of his job. Then eventually Israel rejected my family unification application.

“I knew if we stayed in the country, eventually we would have to separate.”

Palestinian rights and freedom of movement is heavily restricted under Israeli occupation.

When the Six Day War ended in 1967, Israel expanded its military occupation into four Palestinian territories and introduced a mandate requiring Palestinians to obtain a colour-coded ID or leave.

Palestinians living in East Jerusalem and Israel were issued blue cards while green cards were issued to Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Heavy restrictions were imposed on green card holders effectively allowing Israel to control their every movement, where they study – and to some degree – who they could have a life with.

“At some point, Israel decided that Palestinians from the West Bank were not allowed to go to Jerusalem,” Suheir said. “And Palestinians living in Jerusalem, like my husband, had to prove that Jerusalem was the centre of their life. They couldn’t leave otherwise they would lose their ID. We were trapped.”

Under Israeli occupation, it is illegal for West Bank Palestinians to travel to Gaza or Jerusalem. Gazans are also forbidden from entering the West Bank and Jerusalem.

The only exception is by issue of a special military permit or a family unification card for spouses who hold different IDs.

After marrying Samer in 2004, Suheir immediately applied for family unification and in the interim was issued a single document written in Hebrew that said she was allowed to live in Jerusalem while she awaited the outcome of her application.

But the few years she spent living in Jerusalem was like “living in a prison”.

“Even though my husband had a blue card, it only meant he was a permanent resident not an Israeli citizen,” Suheir explained.

“So we could live in the city, but we had no rights.”

And because Suheir had a green ID, she had no right to drive or to obtain health insurance.

But the worst part Suheir said, was the daily intimidation and “humiliation” Palestinians were subjected to by Israeli soldiers.

Suheir recalls an incident that happened while walking the streets of Jerusalem with her babies in arm.

“I remember seeing school kids around 12 or 13-years-old stopped by Israeli Jeeps and they would be humiliated on the street,” she said.

“They would take their bags, beat them, shout at them and make them stand for hours and hours. I used to look at my babies and think ‘I don’t want my kids to go through this’.”

The threat of losing their home would also loom over them with Palestinians required to pay exorbitant property taxes and prove that Jerusalem was their city of residence or have their residency revoked.

“I remember our neighbour’s house being demolished under the pretext that they didn’t have a permit to live in Jerusalem,” Suheir said. “That’s how they made our life like hell.”

There’s a hard edge to Suheir’s voice now.

“But we Palestinians are resilient. It’s in our blood.”

Education is resistance

Suheir is 19-years-old when she breaks into Birzeit University in 1990.

It’s the first time she’s ever laid eyes on its white buildings and sprawling pine trees since starting her degree in secret almost two years prior.

“Back then studying was illegal,” Suheir said. “We used to hide our books inside our clothes. I would go to my teachers house or stay in my dorm and study in secret.”

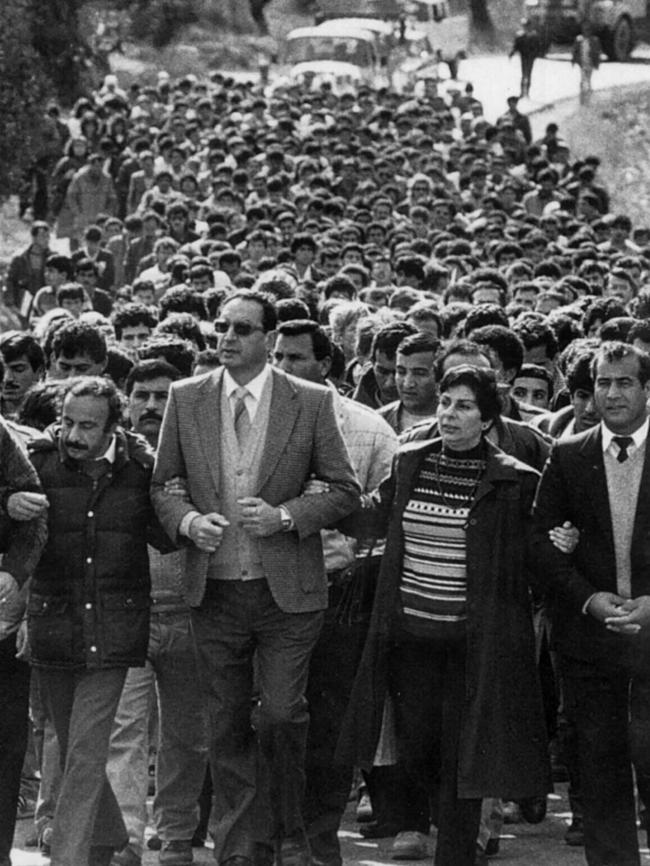

In the wake of the First Intifada in 1987, universities across Palestine were raided and shut down by the Israeli army.

But Birzeit University, tall and imposing atop a northern Ramallah hill, is steeped in the political strife of the Palestinians who have sought an education there for decades.

Within its wall, students have been kidnapped and later assassinated. Its fertile grounds, once home to olive trees, bore the weight of hundreds of students demonstrating and protesting against the killing of their fellow students.

Between 1981 and 1987, it had been shut down more than eight times.

On November 21, 1984 Gazan student Sharaf Khalil Tibi, injured by Israeli soldiers, bleeds out for 25 minutes in the back of an ambulance Soldiers block the vehicle from leaving and Sharaf becomes the first Birzeit student to be killed by occupational forces.

Despite the closure, the university continued accepting and teaching students in secret.

“For us education is resistance,” Suheir said. “Palestinians are some of the most highest educated people in the world.

“And we loved studying because there was nothing else we could do, everyone in Palestine studies. But people need to understand, living under occupation was not pleasant at all.

“In the First Intifada we did throw stones. And when we were unable to study (at university) we studied in secret. We wanted to raise our voice and be part of it because the Israelis were bombarding us and killing us and we were just throwing stones.”

“We really hoped that one day we would be free.”

Three years after she breaks into the university, the Oslo Accords are signed and people take to the streets in celebration.

“People were finally talking about peace, we went into the streets celebrating thinking ‘Oh my God, this is all going to be behind us,” she said

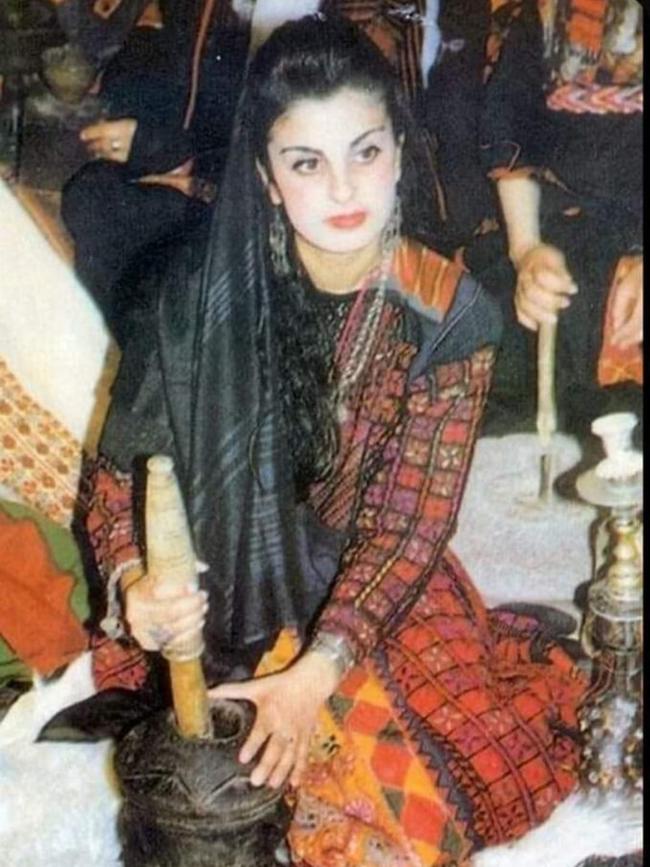

On January 6, 2000 Suheir’s sister, recently engaged, invites her to a party in Ramallah. Reluctantly, she agrees to go and there she meets Samer. He’s young and handsome and all the girls want to dance with him.

He spots her as she walks into the room and is taken aback when she says no to him.

But after so much misery, Suheir says, Palestinians learn to take joy where they can.

She dances with him and forgets the sadness for a while.

Six months later, the Accord fails. The Second Intifada breaks out

“It was a trap.” She takes another sip of her coffee.

A home among the hills

Two years after the incident at Qalandiya Checkpoint, Suheir goes to her boss and asks them to send her to Australia for work.

“I was lucky because at this time (my workplace) was beginning to post people overseas,” she said.

It was their last hope to keep their family together, Suheir said, and in 2010 she was posted to Australia.

For the next ten years she worked as a Palestinian public servant in Canberra working diligently to raise awareness for the plight faced by her family and countrymen.

“But in the back of my mind, I was always afraid that I would have to go back to Palestine,” she said.

Eventually with the help of a human rights lawyer, Suheir and her family were granted an Australian citizenship and in 2021 she left her old job and settled in the Gold Coast.

But the Palestine she longs for lives almost four decades ago, in the small Christian town of Beit Jala where a hundred olive trees grew on her father’s farm.

Suheir recalls her childhood home by the rich taste of olive oil, the grit of the earth and the sting of branches scraping her small arms.

“I remember growing up, picking those trees,” she says. “And to be frank with you I hated picking those olives – it was painful and dirty.”

“I never understood how valuable these trees were for my father. I remember telling him one day – ‘oh why do you care? Sometimes I feel you love your trees more than me.”

But her father, face weathered by the Palestinian winds, replied: “Ya binti, my daughter, it is not about the olives we harvest and the oil we make, it is the trees themselves and the land that matters.

“Every single tree has its own character, I grew them from little trees, took care of them, observed them growing up and saw myself grow older with them. They are a part of me. I care for them like I care for you.

“The olives and oil they give me is the gratitude for the love I give them”

In 2020, Israeli settlers seized her father’s farm and the Cremisan Valley annexed with plans to build a separation wall barring locals like her father.

To this day Suheir is unsure what happened to the olive trees, but she wishes she could return to pick their fruit one more time.

“People don’t leave their countries because they want to,” she said.

“Why would you leave when you have your ancestors there, and the stories of your grandparents – but you put that behind you because you just want what’s best for your kids.

“I want my kids to grow up normal human beings and to feel like they are human beings. But the younger generations are being reminded that they are not human. That you’re less human because you are Palestinian.

“How many more need to die before the world wakes up?

“I don’t know who said it, but I’ve been thinking about this: When the power of love overrides the love of power, then maybe we can have a better world.”