Inquiry into Kathleen Folbigg murders finds babies died of natural causes

New evidence into the deaths of the children of a woman once dubbed Australia’s most infamous female serial killer reveals how they died.

Breaking News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Breaking News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Kathleen Folbigg’s four children did not die at their mother’s hand, an inquiry into her murder convictions has found.

Ms Folbigg, 55, was convicted of three counts of murder and one of manslaughter in 2003 after her babies Patrick, Sarah, Laura and Caleb died in suspicious circumstances.

The Folbigg children died between the ages of 19 days to 18 months between 1989 and 1999.

Despite many appeals, Ms Folbigg has always insisted she didn’t kill her children.

Former NSW chief justice Tom Bathurst KC was tasked last year with considering whether there was reasonable doubt that Ms Folbigg was wrongfully convicted.

On Monday, Mr Bathurst submitted a memorandum outlining his findings to NSW Attorney General Michael Daley which said he had reached “a firm view that there was reasonable doubt as to the guilt of Ms Folbigg for each of the offences for which she was originally tried”.

Key points from the memorandum to the AG include that there was a “reasonable possibility three of the children died of natural causes”.

“In the case of Sarah and Laura Folbigg, there is a reasonable possibility a genetic mutation known as CALM2-G114R occasioned their deaths,” the findings said.

In relation to the death of the fourth child, Mr Bathurst found “the coincidence and tendency evidence which was central to the (2003) Crown case falls away”.

“In relation to Ms Folbigg’s diary entries, evidence suggests they were the writings of a grieving and possibly depressed mother, blaming herself for the death of each child, as distinct from admissions that she murdered or otherwise harmed them,” Mr Daley found.

The February inquiry heard evidence from experts about new scientific developments that could potentially prove some of her babies died of natural causes linked to a genetic mutation.

This genetic mutation was not discovered by medical scientists until years after the deaths and would not have been investigated at the time, the inquiry was told.

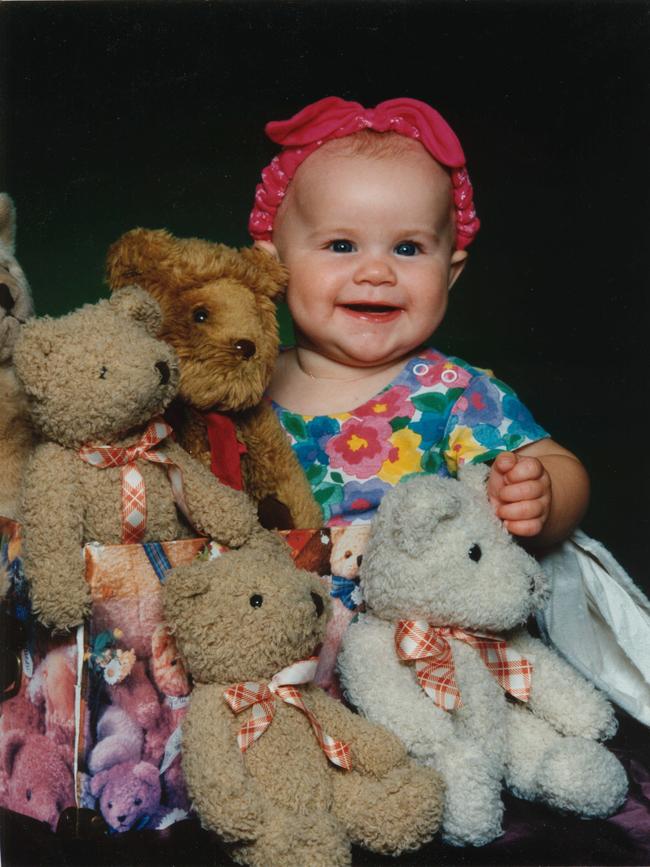

A 2021 scientific report suggested at least the deaths of Laura, who died at 18 months, and her older sister Sarah, who previously died at 10 months, were linked to a rare genetic variant.

Sarah and Laura Folbigg

During the inquiry medical experts discussed the possibility that Laura and Sarah had the rare genetic mutations CALM2G114R, which is linked to long QT syndrome, a heart-signalling disorder that can cause fast, chaotic heartbeats or arrhythmias.

The inquiry was also told the girls’ deaths might be linked to catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), a condition characterised by an abnormal heart rhythm or arrhythmia.

Professor Carola Vinuesa told the inquiry that she had contributed research on the rare mutation CALM2G114R and hypothesised that the four Folbigg children most likely died from some form of cardiac arrest that led to unexplained death.

Dr Vinuesa told the inquiry that Sarah and Laura had this variant and the Folbigg boys also died from similar issues relating to the sudden unexplained deaths.

Other alternatives to cause their deaths

However, the inquiry did hear from others who dismissed the genetic mutation theory.

Cardiovascular genetics expert Dominic Abrams told the inquiry it was “unlikely” Laura and Sarah died from the mutation.

He said there was a lack of evidence proving their exact cause of death.

“Whilst a cardiac arrhythmia related to the calmodulin variant cannot be definitely excluded, I believe the likelihood this was responsible for the deaths of Laura and Sarah is low,” he wrote in a report tendered to the inquiry.

“There is no compelling evidence to support any … environmental triggers as clear factors that may have increased arrhythmia susceptibility.”

Dr Matthew Orde told the inquiry he’d analysed records of Laura’s heart tissue, known as slides, to determine if myocarditis, commonly known as inflammation of the heart, had caused her death.

He said the slides he assessed showed clear signs myocarditis was present and was the likely cause of death, but from a forensic pathologist’s perspective, he would need to look at the “big picture”.

“In my experience as a forensic expert, the extent of degree of inflammation in Laura’s heart slides creates a very compelling contention for the cause of death,” Dr Orde said.

“All I’m trying to draw attention to is, on the basis on the slides, I see a potential cause of death, but I can’t exclude other factors having contributed.”

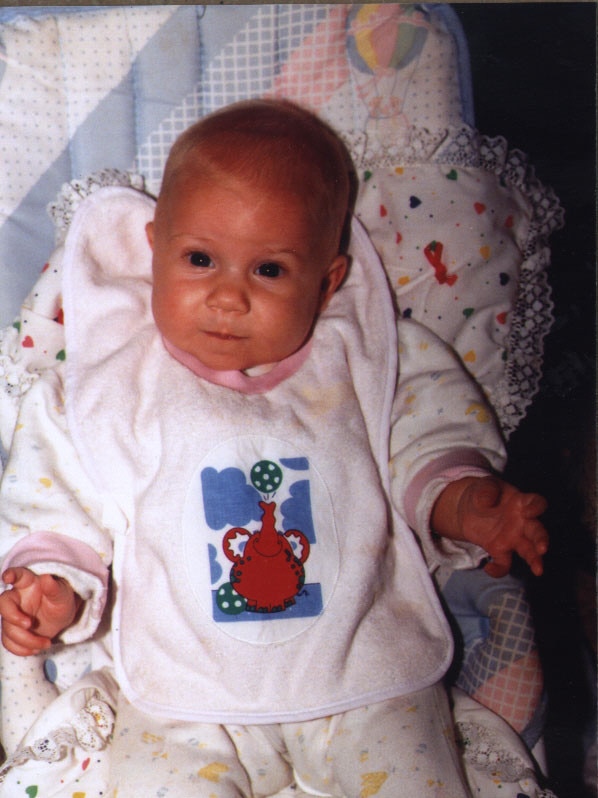

Patrick Folbigg

The inquiry was told both Patrick and Caleb most likely did not carry the same variant their sisters shared.

Their cause of death was a little more difficult to determine as neither boy shared any similarities other than their sudden unexplained deaths.

An autopsy on Patrick found his cause of death to be an acute asphyxiating event resulting from an epileptic fit.

The inquiry was told Patrick had been taken to hospital on October 18, 1990, after his parents had found him struggling to breathe.

The then four-month-old boy was also reportedly blue in colour when he was rushed to hospital.

Neurologist and sitting MP Monique Ryan told the inquiry that Patrick’s sudden death could have been linked to a brain injury he suffered during this medical episode.

Dr Ryan said it was most likely around October 1990 that Patrick would have had his first seizure.

“He had an uncontrolled epileptic seizure and more likely than not caused his death,” she told the inquiry.

“Sometimes when babies have seizures they can be relatively subtle, but they (the parents) would recognise the babies were having unusual events even if they didn’t recognise them to be a seizure.”

However, Dr Ryan said she questioned whether the seizures had brought on a brain injury linked to lack of oxygen that ultimately caused Patrick’s death because of how quickly he initially recovered.

“The baby’s eyes were open, he appeared awake, but he was less responsive than usual and the fact that he was only responsive to painful stimuli indicates how unresponsive he was,” Dr Ryan said.

“If a baby’s had a severe brain injury related to breathing problems … for it to be severe enough … I would have expected he wouldn’t have recovered as quickly as he did.”

Patrick had begun to respond to medical attention within 15 minutes of attending hospital on October 18, 1990, the inquiry was told.

“He was behaving more normally, which would be inconsistent with a severe hypoxic brain injury,” Dr Ryan said.

“The kidneys and the heart would show signs of hypoxic brain injury as well.

“The blood tests done initially which were limited were relatively benign.

“He wasn’t sent to intensive care, which all argues against an acute severe hypoxic brain injury at that time.”

She said while his seizure was a “fairly significant one”, Patrick didn’t continue to display typical behaviour for a child with ongoing issues relating to the brain injury.

Dr Ryan said this could be the result of a diagnosed genetic disorder scientists hadn’t discovered yet.

She said another possibility was Patrick’s death could be related to “stroke-like episodes”, linked to energy failures within the brain.

“It was pretty clear something happened on the 18th of October which was fairly profound, before that date Patrick Folbigg was felt to be normal,” she said.

“He was not neurologically normal (after October 18) … there has to have been some sort of brain injury at or around that time.

“I think it’s more likely he had an underlying condition that manifested on that date.”

The inquiry heard evidence from medical experts that genetic science was a fairly new field, with discoveries being made every day about new mutations.

“The fact a definitive abnormality wasn’t found on Patrick’s genetic testing does not to me indicate it wasn’t a genetic disorder,” Dr Ryan told the inquiry.

“If he was born today and we did a whole genome sequencing … and it was negative, we would just have to wait and see. We’d do it every five years.

“Unfortunately, he died without a definitive diagnosis. Unfortunately, these sorts of things happen.”

Dr Ryan said she had patients under her care where she had made a diagnosis “long after” their deaths.

“It’s very often we don’t have sufficient timeframes within a baby’s life that we have time to make a sufficient diagnosis,” she said.

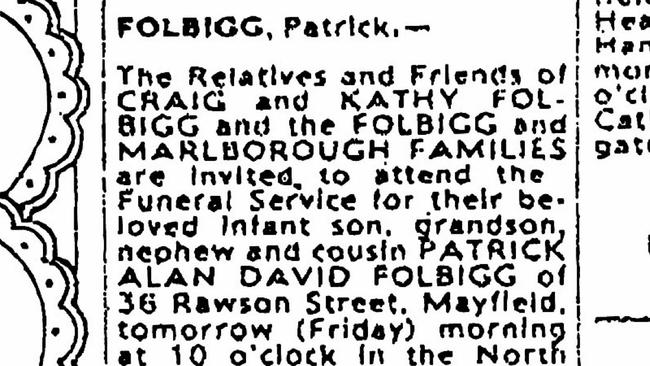

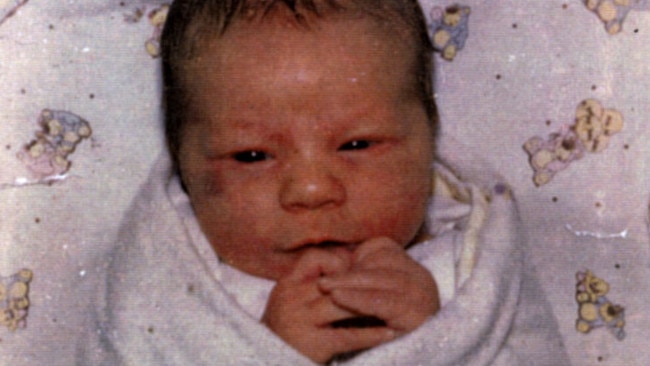

Caleb Folbigg

The eldest of the four siblings, Caleb died at 19 days old in Newcastle.

However, the inquiry was unable to determine the cause of his death.

The Crown’s case in 2003 had relied on circumstantial evidence after the four post-mortems failed to determine what caused the children’s deaths.

But prosecutors pursued the allegation, which ultimately turned into a conviction, that Ms Folbigg had smothered her four children, including Caleb.

Ms Folbigg was found guilty in 2003 of Caleb’s manslaughter.

Originally published as Inquiry into Kathleen Folbigg murders finds babies died of natural causes