A tale of two cities: Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor

THEY are the cities where the war in the Pacific began and ended for the US and Japan ... discover the history and the future in Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor and Japan’s Hiroshima.

Travel

Don't miss out on the headlines from Travel. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHAT’S the difference between “remember” and “never forget"? About 6800 kilometres. That’s the distance between Hiroshima, on Japan’s Honshu Island, and Pearl Harbor, in Honolulu, Hawaii.

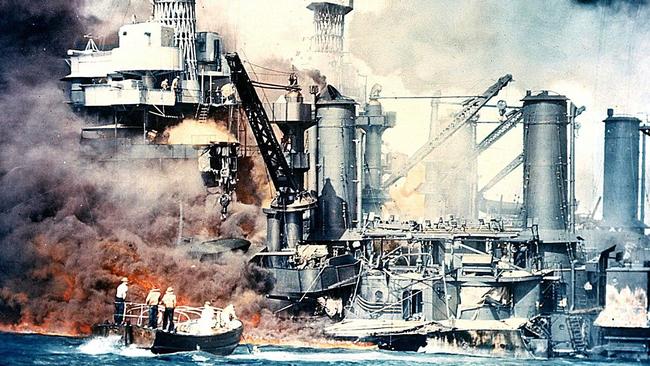

On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, killing 2403 Americans, pulling the US into World War II and turning the tide of the war.

American soldiers poured into Europe and across the Pacific in the name of freedom. Their war cry was “Remember Pearl Harbor!” and their mission was to avenge that “date that will live in infamy”.

The climax, of course, came in August 1945, when the US wreaked unprecedented destruction and loss of life on two Japanese cities.

The rights and wrong of this action continue to stir strong feelings. The Japanese had established their brand of wartime brutality as far back as 1931, when they invaded China. Their atrocities there and elsewhere had left an estimated 10,000,000 dead by 1945. The Imperial Japanese Army fought with fanatical enthusiasm and treated captured foes and overrun nations with terrible cruelty.

The bloodshed, and the hatred it inspired among the Allies, helped to justify the unthinkable final offensive against the Empire of Japan. The US concluded that the only way to stop Japan and end the war was to employ the superweapon they’d been working on for three years.

And so, on August 6, 1945, the American bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb (code named Little Boy) over the southern Japanese city of Hiroshima. An estimated 150,000 people were killed.

On August 9 another bomb, Fat Man, was dropped on Nagasaki, killing some 75,000 people. After that the Japanese surrendered.

More than seven decades later, I take a holiday that encompasses both ends of those terrible years: Hiroshima and Honolulu. In the intervening years the threat of nuclear Armageddon has never been far away.

At the end of World War II, it was said that in Hiroshima, “nothing would grow for 75 years”. Happily, the city has proven the world wrong and rebuilt itself stronger than ever.

When the dust of the A-bomb cleared, only two buildings were left standing in Hiroshima — a bank and the Exhibition Hall. They stand today in post-bomb condition. The hall’s distinctive dome is an international icon for the anti- nuclear movement.

There’s a chill in the air as I stand before the “A-Bomb Dome”, as it’s known. It’s hard to reconcile the vibrant, modern city around me with this empty shell. From the dome’s east end I can see both a 7-Eleven and a McDonald’s. Clearly, in this case, to the victor went the spoils.

The dome was a mere 150 metres from ground zero, a hospital. Today, a new hospital stands there.

Across the water from the dome is the A-Bomb Peace Memorial and Museum. Inside, visitors are confronted by a series of graphic images of the destruction wrought by the bomb. Seared flesh, melted fingernails, tongues covered in cancerous growths. The atomic fire incinerated one anonymous victim as they sat on the steps of Sumitomo Hiroshima bank. The steps, now on display in the museum, show a dark stain in the shape of a body on the bleached stone.

Two things strike me about the museum. One is a subtle but evident lack of culpability. At no point is there any acknowledgment or understanding about why the bomb was dropped. Wrong or right, the US has stuck to its justifications for using nuclear force — that the Japanese wouldn’t have surrendered without it, and that it wanted to avoid a planned full-scale invasion of Japan that would have cost many more lives. The museum doesn’t go into any of that, presumably to remain apolitical.

The second thing is the overwhelming message to “never forget” what happened, so that it will never happen again. Nobody but the worst warmongers wants another nuclear bomb dropped on humanity, especially because the power of today’s weaponry makes Little Boy look like a toy.

Hiroshima sends mixed messages today. It lives again, stronger than ever.

Though defined by war, it stands as a monument to peace. Had August 6 been cloudy, the Enola Gay would have dropped its load on Kokura, the back-up target.

And so Hiroshima achieved worldwide fame and Kokura was relegated to Trivial Pursuit status. (Kokura was lucky again on August 9, when clouds forced the US mission to drop Fat Man on Nagasaki, that day’s back-up target.) The bomb defines Hiroshima. That peace is the lasting message speaks to the humility of the Japanese people.

Across the Pacific Ocean, at Pearl Harbor, humility is in short supply. The bellicose call to “remember Pearl Harbor” is loud and clear when I’m there on the overcast afternoon of December 7, 2016 — the 75th anniversary of the attack. Earlier in the day the Pearl Harbor memorial grounds were full of people paying tribute to those who had died, including 55 or so civilians who were killed by friendly fire.

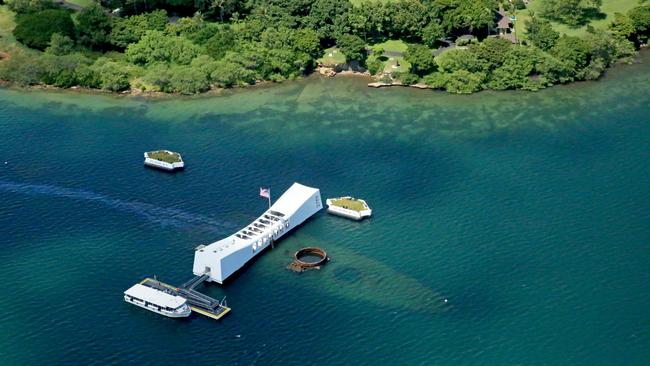

Now, as the late afternoon sun drops, the jingoism and bombast are gone, and the grounds are quiet. Each day, 1300 free tickets to the sunken battleship USS Arizona are offered on a first-come, first-serve basis. The last trip to the Arizona has left for the day, leaving me alone on the Walk of Contemplation. But all I can contemplate is the discrepancy between the two messages. There’s nothing peaceful about Pearl Harbor. It’s still a working military base, so any declaration that “it should never happen again” would seem insincere.

The USS Arizona, still a tomb to 1,102 bodies never recovered, lies where it sank on the bottom of the harbour. It’s straddled by a peculiar memorial that looks like a giant Chinese finger trap. The name of each victim is inscribed on a wall of honour.

Neither the ship nor its doomed crew has ever been allowed to pass on to the next life. They’re still down there, left on parade for eternity by a country seemingly happy to exploit them for sympathy.

Hiroshima’s A-Bomb Dome, on the other hand, is empty. Its victims were largely anonymous. There’s no wall of honour. In fact, there are barely walls. A visit to the A-Bomb Dome is sobering precisely because that’s all that’s left. Hiroshima promotes peace and love for humankind, and the message that a nuclear attack should never happen again. Pearl Harbor promotes the message that such an attack will not be allowed to happen again.

Night and day. Love and hate.

America’s revenge didn’t stop when 225,000 civilians paid for their lives in two nuclear firestorms. That fire still burns today, all around the world. As if we could ever forget.

IF YOU GO

GO

Qantas, ANA and Japan Airlines operate flights to Hiroshima with stopovers in Tokyo. The city is about 50 minutes’ drive from the airport, but a train is your best bet for price and travel time.

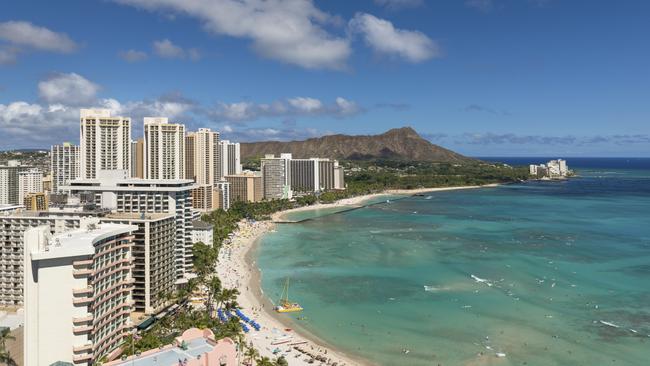

Direct flights from Sydney to Honolulu are operated by Hawaiian Airlines, Qantas and Jetstar. Pearl Harbor is about 30 minutes’ drive from Waikiki and just 10 minutes from the airport. Buses may take a bit longer, but they’re much cheaper than taxis.

STAY

Hiroshima Prefecture contains plenty of hotels, and the A-Bomb Dome is within walking distance of the city centre.

There aren’t many options for accommodation at Pearl Harbor, but Waikiki features plenty of resorts a stone’s throw from the beach.