Retrial by media: The danger in our obsession with true-crime

TRUE crime delivers mega-selling books and highly rating television shows — but many forget that at the centre of each story is a victim without a voice

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SHE was 25, one of five children, and grew up in Calumet County, Wisconsin. She took photos for a living. She loved karaoke. She coached her little sister’s volleyball team. She had cropped brunette hair, brown eyes, and was 1.67m tall.

That’s all anyone but her friends and family know about the life of Teresa Halbach. But more than 20 million people know about her death. She was killed in 2005, and her charred bones were found in a residential burn pit.

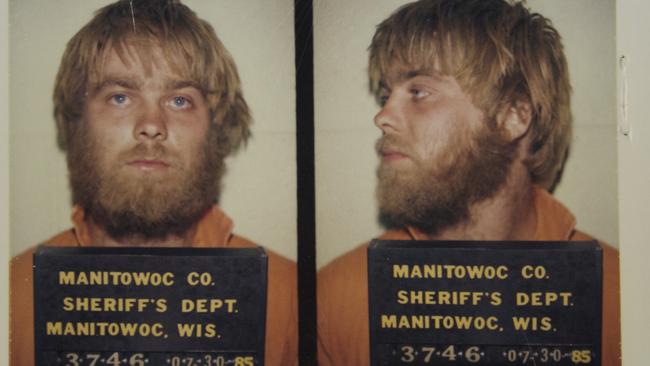

The Netflix series about the trial of the man accused of her murder, Steven Avery, has been one of the most talked-about true-crime documentaries of the past decade. Making a Murderer has made the Halbach and Avery names famous, and ensured they will be forever linked in the popular consciousness.

That thought is no doubt deeply traumatic for Halbach’s family, but the unhappy fact is that the true-crime genre is perennially popular, and at the core of each story is a victim without a voice.

True crime gives us some of our biggest-selling books, our most-watched TV shows and our most talked-about films.

Netflix is producing a second season of Making a Murderer, and will soon air a film examining the case of Amanda Knox (aka “Foxy Knoxy”), an American accused, then acquitted, of murdering her roommate while they were studying in Italy. “Was she a cold-blooded psychopath who brutally murdered her roommate,” the media release asks, “or a naive study-abroad student trapped in an endless nightmare?”

At the centre of these stories is the victim — the only person who can’t have their say.

Turning private tragedy into public entertainment is not new, and has always been controversial.

There’s an overriding importance in lifting the lid off the dark black box that is a courthouse, and letting the public see what happens in police stations and court houses

But in courtroom parlance, there is one possible defence for dragging a grieving family through the agony of having their child’s death judged by the court of public opinion: justifiable cause.

That’s the issue raised by Making a Murderer: do the questions asked about the fairness of the justice system and the legitimacy of Avery’s conviction outweigh the rights of the victim’s family to the closure they received from the court’s original guilty verdict?

Avery’s lawyers, Dean Strang and Jerry Buting, are bringing their speaking tour to Australia in November. They will answer questions from the public, including, they expect, that one.

Critics argue the series was biased in Avery’s favour, and supporters say it revealed an innocent man was framed. But Strang believes Making a Murderer is the tale of a flawed justice system, told through the prism of Avery’s story.

“I feel deeply sorry that, unavoidably, the victim’s family carries the burden disproportionately of any exploration of a nonfictional crime,” he tells Stellar.

“I believe this was not a voyeuristic exploitation of a young woman’s death, but a good faith exploration of the criminal justice system’s response to that death and its efforts to mete out justice to the men [Avery and his nephew, Brendan Dassey] charged with her murder.

“There’s an overriding importance in lifting the lid off the dark black box that is a courthouse, and letting the public see what happens in police stations and court houses. Again the burden falls disproportionately on the victim’s family, but there was a sharp difference between this as an exploration of the system after a death, and an exploitative voyeuristic treatment revelling in the fact of the death.”

We focus on other things — how does someone become a murderer — rather than how do we live when someone has been brutally murdered

Strang says only God knows whether Avery is guilty or not. “But you only have to be a reasonable observer to realise it wasn’t proven beyond reasonable doubt. Whether he is innocent or not, I do not know, but I do know he was entitled to a not-guilty verdict if you were a reasonable observer of that trial. In that sense, I think it was a failing of the criminal justice system.”

True crime intrigues us because it’s about actions and impulses most of us will, touch wood, never experience. “There’s a part of us that’s fascinated by how someone can do something like that to someone else,” says Katie Seidler, a forensic psychologist.

We aren’t too troubled by empathy, as we don’t identify with the victim — partly because, “People are afraid of being victims of crime, so they don’t connect with that, as it makes them feel vulnerable or insecure,” she says. “We focus on other things — ‘How does someone become a murderer?’ rather than, ‘How do we live when someone has been brutally murdered?’”

Another reason audiences don’t get caught up in their empathy for the victim is because he or she is often a one-dimensional character. Like Halbach, we don’t tend to know much about them.

When we do know more, we are more likely to empathise, says Seidler. “Stephanie Scott [the NSW teacher murdered just days before her wedding] is a really strong presence in the media because people can really connect with her story. She is very personalised. So is William Tyrrell [the three-year-old abducted two years ago]. A lot of other victims are nameless, or identity-less.”

University of Sydney law professor David Hamer hasn’t seen Making a Murderer because it feels too much like work — he specialises in wrongful convictions. But he says there needs to be a balance between the rights of victims’ families to a final verdict on one hand, and efforts to ensure a correct result on the other.

He believes that even in Australia — a system fairer on many counts than the US system that convicted Avery — there is an emphasis on finality over accuracy. “Yes, it would be upsetting for a victim’s family not to have finality,” he says. “They think the right person is in prison, and then the whole thing is dragged up again. But they can’t have an interest in the wrong person being in prison.

“You have to have finality. You have to protect finality. You can’t have a trial verdict provisional and open to review. But you have to balance finality with the need of accuracy, to make sure the right result is reached.”

Howard Brown, from VOCAL, a support group for the victims of crime, agrees. It is upsetting for families to have the case brought up again, he believes, but if it is in the public interest, and not done for salaciousness alone, then most understand.

“The public needs to know how the justice system does, and sometimes does not, work,” says Brown. True crime can also help victims’ families raise awareness when a perpetrator has not been caught.

If there is a question over the legitimacy of a conviction, Brown says victims’ families would not want the wrong person going to jail. “They want the person who committed a crime punished, not just anyone,” he says. “The last thing they want is to be complicit in that miscarriage of justice.”

Halbach’s family was invited to participate in Making a Murderer, but declined. On the eve of its premiere, they issued this statement: “Having just passed the 10-year anniversary of the death of our daughter and sister, Teresa, we are saddened to learn that individuals and corporations continue to create entertainment and to seek profit from our loss.

“We continue to hope that the story of Teresa’s life brings goodness to the world.”

Dean Strang and Jerry Buting will speak at the Sydney Opera House on November 3; QPAC, Brisbane, on November 6; and Hamer Hall, Melbourne, on November 8.

Originally published as Retrial by media: The danger in our obsession with true-crime