‘Increased mass violence’: Fears for Australia

Global events like the election of Trump as well as the horrific rampage at Bondi Junction is exposing a key problem Australia needs to face.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Experts are sounding the alarm on the growing divide between boys and girls in Australia, warning that the “demonisation of diversity and inclusion” globally will lead to more mass violence incidents at home.

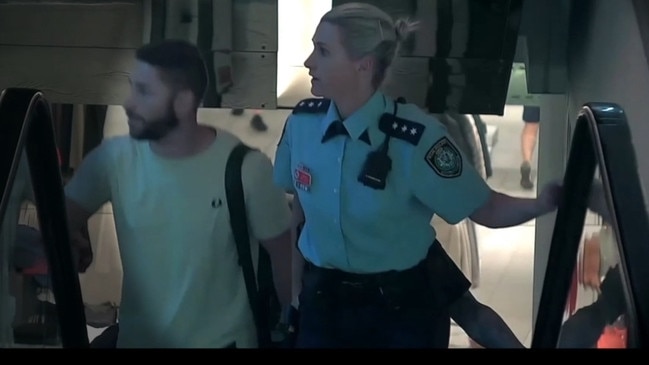

It comes as a coronial inquest takes place into the deadly stabbing rampage at Bondi Junction Westfield in April last year.

Chilling evidence has emerged that killer Joel Cauchi had made searches into mass stabbing incidents in Australia and serial killers and had a “preoccupation with death and murder” in the lead-up to the fatal attack.

Out of the six victims murdered by Cauchi, five were women. Of his 16 victims, just three were men – but the police officer in charge of the investigation has been quick to shut down a theory that the killer was targeting women.

However, given the high number of female victims, the inquest lays bare concerns over growing misogyny and youth radicalisation in online spaces, according to University of Melbourne’s Dr Sara Meger, who specialises in international security and gender in international relations.

Worryingly, this very issue is playing out in Australia’s schools. Teachers have told Dr Meger they are very concerned.

She has also heard from the security sector in Australia that “there is a fear of increased mass violence occurring as a result of this kind of radicalisation of boys” from being online.

“I think the Australian government is also aware of this and they’ve taken much more interest in … the relationship between misogyny and youth radicalisation, especially after the Bondi Junction attack,” she said.

Dr Meger said the devastating rampage was a “wake up” call for governments and she understands that when it happened security services and policymakers did not have the appropriate framework to make sense of it.

The Bondi Junction attack was Sydney’s worst mass murder in more than a decade and the inquest, which has 50 volumes of evidence, is examining the level of preparedness for an active armed offender.

“It was a mass violent attack resulting in several deaths, which is of course significant. So the various Commonwealth and state government agencies recognised that they needed to act to prevent this kind of thing from happening again,” she said.

“Unfortunately, however, ASIO defines terrorism as either politically or religiously motivated. But they adopt a rather narrow understanding of what is ‘political’ – that is, linked to an organised political group or coherent ideology. They didn’t have a means of understanding misogyny as political unless a person actively subscribed to incel ideology.”

There was a concerted effort after the Bondi attack to develop better policy frameworks to understand and prevent this “type of mass misogynistic violence from recurring”, she noted.

“I think Bondi was a wake up call and the sense I get is that this has become a priority issue for many Commonwealth and state agencies,” she said.

This has included policing the online space more heavily, she said.

“So there’s a recognition that something about these misogynistic and violent discourses online is appealing to young Australians, especially young Australian men or boys,” she explained. “This is partly behind the desire for the social media ban in controlling or limiting access to the kind of hateful content that young people are being exposed to and the harms of the algorithm.”

But Dr Meger said there is no political will to categorise violence against women as terrorism.

“I think because it would just implicate way too many men in our society, including politicians, lawmakers, law enforcement,” she said.

“I think there’s a lack of political will because even most abusive men think they’re not part of the problem. They justify their behaviour through I was provoked, it was a one off, I’m not really like that, rather than seeing it as quite systemic.”

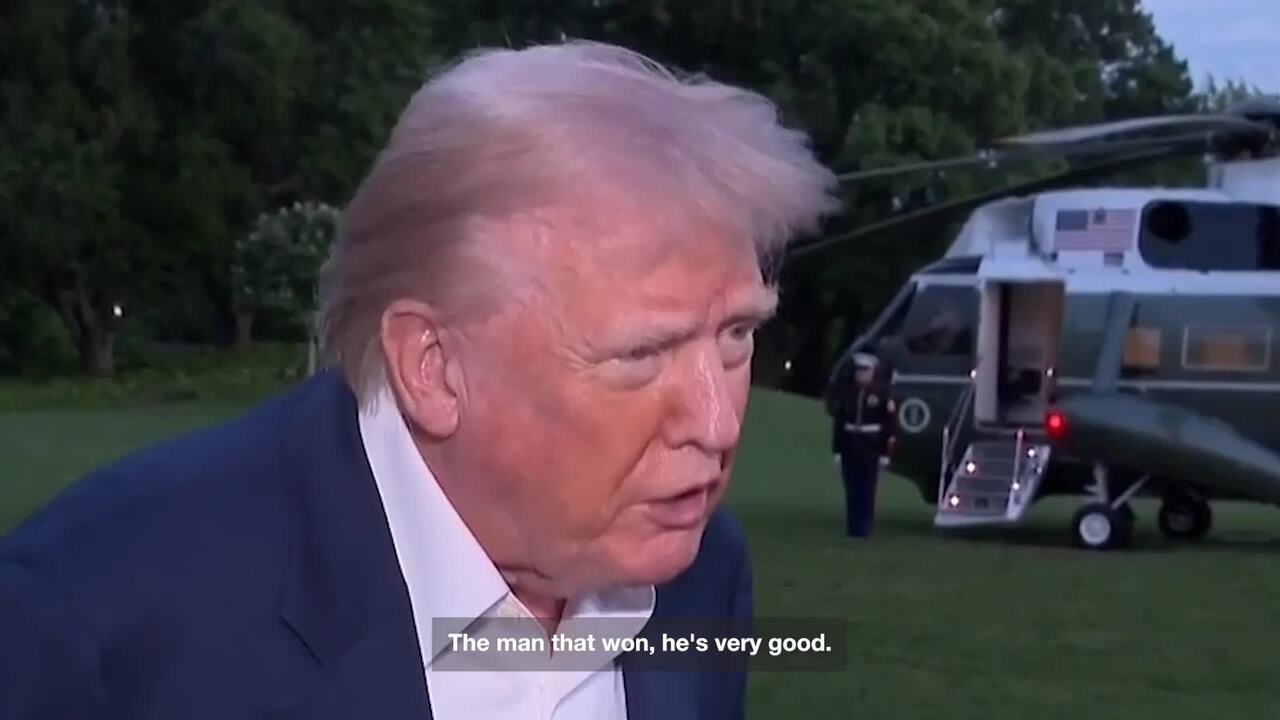

The issue also hasn’t been helped by the election of US President Trump, Dr Meger said, who appears to have emboldened “people to express really misogynistic views”.

“It’s beyond conservative, right? It’s misogynistic and anti-women or anti-feminist values that it feels like this is socially acceptable now when it wouldn’t have been before,” she said.

President Trump has been on the attack from early on. First there was an announcement that he was ending “the tyranny of so-called diversity, equity and inclusion policies all across the entire federal government” and the military, with a knock on effect into the private sector.

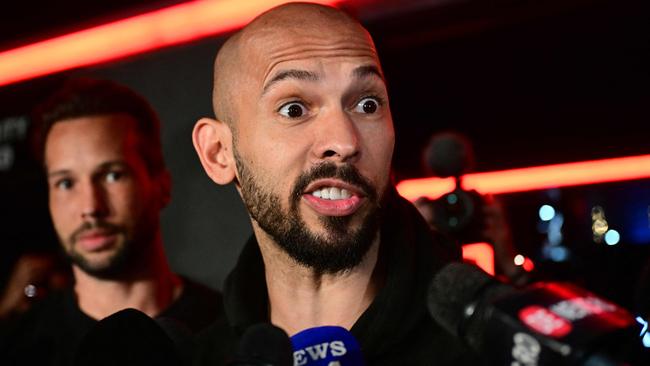

Reports then emerged that his administration had intervened to have self-described misogynist influencer Andrew Tate, who is accused of rape, human trafficking and money laundering, freed from travel restrictions in Romania.

Dr Meger said at first she questioned why the president of the most powerful country in the world would “expend political capital” on Tate – “somebody that doesn’t do much for him”.

But then she realised it was a “powerful political signal to his base”.

“Misogyny is kind of fundamental to his political position and to his political priorities. And it’s another way of signalling to his supporter base of: ‘I’m more with you than I am against you’,” she said.

“What’s concerning is the demonising of diversity and inclusion and that is somehow the root cause of men’s disempowerment.

“Because as soon as we retreat from these very liberal principles of equity and valuing diversity, it means we could theoretically have a return to very discriminatory hiring practices or more structural barriers reintroduced in workplaces that limit women’s full participation or maybe reduced maternity leave provisions.”

However, Dr Meger said these misogynistic ideas initially begun to gain momentum online as they are seen as “edgy” and give men and boy’s “social capital”.

“I think the more it is in the public sphere, the more publicly acceptable it becomes,” she warned.

“It’s undermining the government messaging of the last few years around zero tolerance of violence against women.”

In 2024, there were 103 Australian women who were murdered while this year’s toll already sitting at 25 at the time of publishing, according to Australian Femicide Watch.

Dr Meger’s research has shown a growing acceptance of “very overt forms of violence against women, especially amongst the younger generation”.

“Australians and young Americans are way more likely to think it’s okay and even right to use violence against a female partner than older generations,” she warned.

Meanwhile Australian National University’s Dr Elise Stephenson agreed there has been a backlash against gender equality in the past few years in obvious ways such as the rollback of abortion rights in the US.

But she’s also seen diversity used as a “scapegoat” for perceived issues in the world.

“President Trump and Elon Musk and others in senior leadership, particularly coming out of the US, have given to voicing and basically normalising sexism and misogyny on an extreme scale,” she said, as well as transphobic or xenophobic rhetoric.

“We’re seeing at that political level a level of attack on, in many cases, very vulnerable communities. Alongside, just over 50 per cent of the world’s population being women, it’s also giving permissiveness to other parts of society to basically revisit ideas that we thought we had long settled.”

But clear evidence is being ignored that gender and social equality brings greater productivity, better teamwork, political and social stability and more prosperous societies, she added.

Dr Meger said despite the global backlash against feminism, the fight is already on.

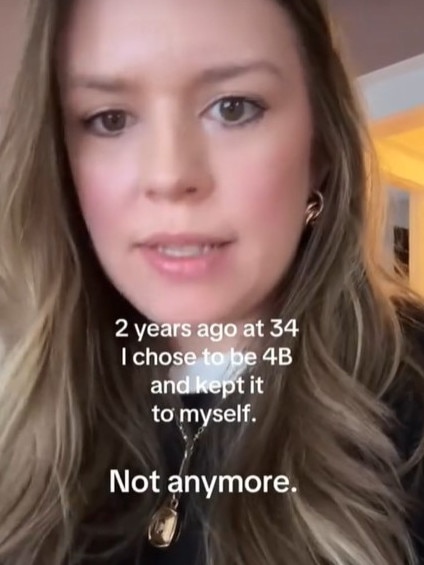

The South Korean 4B movement, which subscribes to no dating, no sex, no marriage and no childbirth, is now gaining an enormous amount of traction in the United States after Trump’s re-election, she noted.

“This is active anti-feminist resistance. Like, if men are going to be so misogynistic and hate us so much, then we will not have sexual relationships, emotional relationships. We’re not going to do anything with men. That’s a very radical stance,” she added.

Dr Stephenson agrees that after the previous Trump presidency there was a surge of women, people of colour and marginalised groups running for politics and that the “takedown” of diversity policies can be an inspiration point.

Also positively in Australia, she said there are stronger legislative and policy environments that make it most difficult for these types of initiatives to be scrapped, including in the corporate world.

University of Canberra’s Dr Leonora Risse also agreed that Australian public policy is still very strongly positioned in a place of fairness, even though these global shifts are happening.

“What we want to be cautious about is we don’t import another countries changes of attitudes or another countries culture wars,” she noted.

“Some of the tech companies like Amazon or Meta, who are saying we are not worried about inclusion and diversity policies anymore, part of that is they are responding to a signal that Trump administration has put out.

“So they are aligning themselves strategically to win favour with the government but what it suggests is they were never really authentically on board with these initiatives anyway.”

Australia also has a strong legal, regulatory and industrial relations architecture which will prevent the country from regressing including the Workplace Gender Equality Act, she added.

However, Dr Risse said the backlash should be wake up call for companies and government that we can’t just cruise along this pathway.

“We should not be complacent. We should be aware that we need to bring everyone on board,” she said.

“What might end up happening is DEI is rebranded so we just call it very healthy inclusive workplace practices that look after the wellbeing of staff and adopt best practices of attraction and retention.”

Meanwhile, Dr Meger said the social media ban for those under 16 brought in by the Albanese government to prevent the “exposure of harmful ideas” is a good first step but said more needs to be done to speak to young people.

“There’s a reason that these narratives have so much purchase for young people. It’s giving them answers to problems that they’re seeking answers to, that they’re not getting somewhere else and not getting from family, school or wherever,” she said.

She said there needs to be a different messaging tool to “open up possibilities of there being other answers besides what they’re getting from these misogynistic and extremist kind of political ideas online”.

However, Dr Stephenson is positive that Australia can withstand the gender equality and diversity backlash, although she said there is still a long way to go.

“Women are still paid about 22 per cent less in this country than men are. The rates of domestic and family violence have skyrocketed … We still have leadership imbalances, particularly across the corporate sector, but certainly in other places too,” she said.

“But I think that this is an opportunity to take up the mantle. Use the evidence on what we know works and try to accelerate some change that way.”

Originally published as ‘Increased mass violence’: Fears for Australia