Gold Coast’s biggest mysteries revealed

EVER wanted to know the real story behind some street art you have seen? How did pine trees get planted in Burleigh Heads? And who is the owner of ‘Matey’ the dog? We reveal the story behind some of the city’s biggest mysteries.

History

Don't miss out on the headlines from History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Who’d have thought the Gold Coast region could harbour so many mysteries. We look into a few local legends.

Burleigh Pavilion graffiti

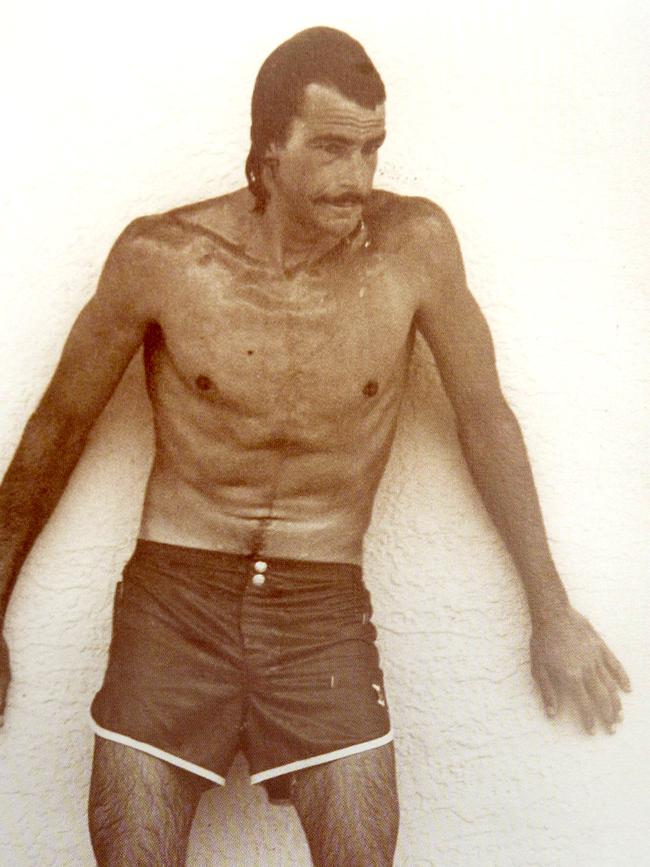

Many will have seen the artwork on the eastern wall of the beachfront Burleigh Pavilion — a lean figure in retro boardies seemingly propped against the amenities block.

It is widely recognised as a commemoration of a moment in surfing history, the fabled stumble of Gold Coast surfer Michael Peterson after winning the first Stubbies Pro contest at Burleigh in 1977.

The event has become the stuff of legend in surfing subculture, the last stand of MP, as he was known, a cult hero mythologised as much for his freakish talent as his enigmatic life.

The inaugural Stubbies Pro heralded the introduction of the man-on-man contest format still used in pro-surfing today.

Peterson, who’d won a string of surfing titles in the early to mid-1970s, had fallen from grace, plagued by a series of no-shows, his notorious drug use and what was later diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia.

He descended on the 1977 Stubbies a menacing figure, staring down his opponents and spectacularly outsurfing them to win the title and the $5000 prize money, a perfect swan song for a champion who was set to disappear from the emerging pro-circuit.

The mural depicts MP clutching at the wall for support after staggering minutes after he won the event. The moment was captured in an iconic photograph that the mural’s artist reproduced in what appears to be a spray-painted stencil.

COUNCIL USING CCTV EQUIPMENT MADE BY CHINESE COMPANY US ACCUSED OF SPYING

As is the way with unofficial works of public art, no one is entirely certain when the mural appeared on the very wall that propped Peterson up that day.

Over the years, MP himself has been photographed standing beside it, before his untimely death by heart attack in 2012 at the age of 59.

Over time, the elements have eroded the red of the boardshorts and the mural’s finer detail, but the figure remains, as much a part of the Gold Coast’s surfing subculture as Michael Peterson’s official memorial at the end of Kirra groyne.

It goes without saying a mural of a man steeped in so much mystery would generate some mystery of its own.

The Burleigh Pavilion is now undergoing a multimillion-dollar facelift and many locals and visitors have wondered what will become of the unofficial artwork.

The Pavilion’s new owner and redeveloper Ben May says the plan is to preserve it.

“I’m a surfer so I’m fully aware of who and what MP was,” he says. “He was a bit of an enigma, pretty special, they reckon the most talented ever really.”

So word got out — they were looking for the mystery artist who’d created the MP mural to return to the scene for some touch ups.

But who do you turn to in the modern world to learn the word on the street? Who else but the local barista.

Marcus Wilkins from Nook, Burleigh’s well-patronised coffee hole in the wall but a stone’s throw from the artwork, started asking questions.

The mystery artist has since been identified, a former sign-writer turned health worker who we won’t name here. But, as with all great mysteries, even when it seems they might be solved, another mystery unfolds.

The initials that now appear with the mural are “MH” and “AB”, not the initials of the artist and not the initials of Michael Peterson. Earlier photographs of the mural show the letters were not there originally but, again, no one is quite sure when they appeared.

Ben May is intrigued.

“I want to know what the MH and AB initials stand for,” he says. “I’d understand if it was MP but I don’t know who the others are.”

And that’s no doubt how the enigmatic MP would have wanted it.

Piano Rock, Tamborine Mountain Road

Many a passer-by has been struck by the discordant sight of a piano perched precariously on the side of a hill on the road between Mount Tamborine and Beenleigh.

The natural rock no doubt looked uncannily like an upright piano for hundreds of years before a local wag (or wags) decided to underscore the phenomenon with a pot of white paint and some strategic black lines.

Mount Tamborine historian and archivist Paul Lyons says it seems the piano first appeared in the 1950s and there are a few local theories on who the original artists were, most likely linked to some of the original families who settled on the mountain.

In earlier times authorities took to the rock with black paint to obliterate the folk art but the white keys, complete with black sharps and flats, regularly reappeared.

Last year ABC Radio presenter Peter Gooch claimed to have spoken to a man, who declined to go public, but said he and his mates indulged in a spot of public artistry one dark night in 1966 but it was a one-off effort.

Art historians would no doubt find there have been any number of artists who’ve done their bit in reinstating and maintaining the Piano Rock paintwork over the last sixty odd years, some more technically proficient than others and some adding their own flourishes.

A piano-playing scarecrow has also been known to make an appearance, not surprisingly around the time of Tamborine Mountain’s annual scarecrow festival, but they too are intermittent performers.

Today Piano Rock is a landmark on the road, still catching out uninitiated motorists, and seemingly maintained by artists unknown.

Jacob’s Well

We’ve all seen the stickers: Where the hell is Jacobs Well?

In case you’re not up with the big news, locals are almost certain they’ve found the location of the mystery landmark the settlement is named after.

Two years ago, Jacobs Well residents Chas Watt and Dave Mayo undertook their own investigations, uncovering a government map from the late 1880s where, through computer magnification, they found a definitive dot with two words: Jacobs Well.

It was a eureka moment that directed surveyors to pinpoint the site, the Lion’s Park next to the boat ramp car park on Jacobs Well Road.

“We were pretty happy to solve the mystery,” Dave says. “The original well mightn’t be there anymore but Jacobs Well has an abundance of groundwater so it makes sense.”

Historical accounts record sea farers, travellers and drovers calling at the well since the mid-1800s. But, of course, uncovering the fabled well’s location only solves half the mystery. Updated stickers should now be asking: Who the hell is Jacob?

Framing the question in such a manner would be highly unsuitable if one theory is correct: that the name is taken from the biblical reference to Jacob’s Well.

Another theory is it was named after Jacob, the oldest son of an early settler at Pimpama Island, who discovered the well when he was out hunting and fishing.

Dave Mayo says the ongoing local research has found there were actually a number of Jacobs in the area at the time and, as is bound to happen when you go digging around in history, at least one of them was not a nice character.

“You wouldn’t want to know him,” Dave says. “By all accounts, he was a bit of a nasty old fella, not kind to the indigenous people or anyone else.”

Not the sort of bloke you’d name a well after perhaps.

The Jacobs Well Progress Association is now trying to get the well site heritage-listed and is pushing for a “significant landmark” to be erected there — “a bit more than a rock and a plaque anyway,” Dave reckons.

Froggy’s Beach

There is something of the chicken and egg here — or, in this case, the frog and spawn.

Did Froggy’s Beach become Froggy’s before or after the beach’s sentry, a frog-shaped rock, was painted bright green?

It’s thought the iridescent Froggy has been overlooking the surf at Snapper Rocks since at least the early 1960s, possibly earlier.

Legend has it the rock was first painted by two brothers Harry and Frank Dorrough. Frank was a handyman who worked for Jack Evans, the man who ran the nearby shark and dolphin enclosures at Snapper Rocks in the mid-1950s, one of the area’s earliest tourist attractions.

The outline of the old ocean enclosures can still be seen today, as can Froggy who’s had many a surreptitious coat of paint since then.

In the interests of public sentiment, the Gold Coast City Council knows well enough to leave Froggy green and when there are reports of vandalism — Froggy has been known to sport spots, stripes and assorted tags over the years — Council workers come to the rescue.

A Council spokeswoman says graffiti is removed as necessary and this sometimes requires existing painted surfaces to be touched up.

It’s not known what particular shade of green Council stocks for the purpose, and certainly the Council is not encouraging such unauthorised public art projects, but it seems Froggy has attained protected species status.

Burleigh foreshore pine trees

It seems the rainbow lorikeets have been screeching on sunset in Burleigh’s iconic Norfolk pines since time immemorial.

But, of course, the heritage-listed pines are not native and almost didn’t get beyond sapling stage after they were planted by a local family in 1934.

Around 100 pines were put in along the shoreline and in what’s now known as Justins Park, named after the Justins family who were local shopkeepers in Burleigh during the 1930s.

It was the Justins brothers who bought the saplings that were transported from Sydney and planted them near the beach, only to find when they went back to tend them, around 60 trees had been removed.

Initial reports blamed vandals but it turned out the local council at the time had decided, in their wisdom, to destroy the trees.

It sparked a public outcry and the council reinstated the pines running along the foreshore up to what’s now the National Park that remain to this day.

Matey the dog

The memorial statue of Matey the dog in Surfers Paradise was struck in 1957 to commemorate a stray, much loved for his habit of accompanying patrons home from the Surfers Paradise Hotel in the 1940s and 50s.

Matey, the kelpie-cross, was an identity among locals and tourists and lived on the streets of Surfers Paradise for 12 years. In all tributes to Matey, he is referred to as homeless but it seems new evidence could turn popular folklore on its head.

Could it be Matey, much like his companions, had a home but preferred to spend his time at the local pub?

Long-time Gold Coast resident Linda Duckworth, who was Linda Cummins, says her parents always told them the famed Matey was their family dog when they lived at Broadbeach.

“Mum said he was constantly nicking off to Surfers Paradise Hotel and would spend days away from home,” she says.

“Mum used to go and pick him up and bring him home but he kept going wandering. She told us she once found him asleep in the middle of the Cavill Avenue and Pacific Highway intersection.”

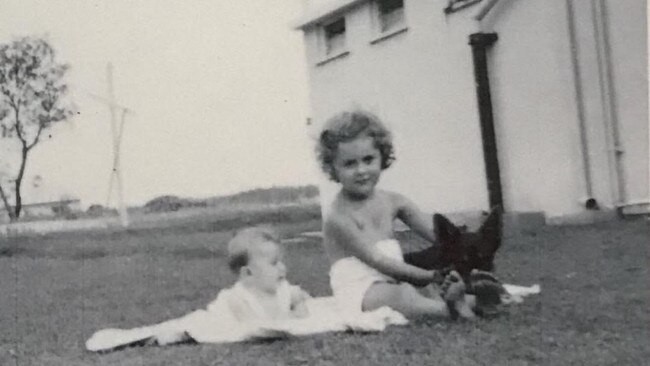

Linda has photos of the dog she believes was Matey when she and her older sister were very young children, probably taken in 1953-54. But it seems no local mystery could be quite so clear-cut.

“My aunt (who’s still alive) reckons we didn’t move to Broadbeach any earlier than 1952 and the old blokes who remember him (Matey) say he was there in the late 40s,” Linda says.

“So I guess that part of the family folklore could be a furphy.”

Perhaps, but what’s a local mystery without a good red herring or two.

The bronze statue of Matey originally stood on the busy corner of Cavill Avenue and the Gold Coast Highway but was relocated to the more sedate Cavill Park some years later where he remains today — a move it seems the real Matey (whoever he was) might not have entirely approved of.

Do It Yourself Road, Tamborine Mountain

Ah, the pioneering spirit. When locals’ requests for a road linking Tamborine Village with the coast repeatedly fell on deaf ears, they decided they’d build one themselves.

In the mid-1950s, four men set to work clearing a path along a ridge, enlisting the assistance of trucks and bulldozers from the local timber mill.

When a rough track emerged, the Tamborine Mountain Progress Association took over the project, coordinating volunteer workers and raising funds through selling produce at a stall at Curtis Falls for more than two years.

By the end of 1959, traffic was able to travel on a narrow gravel road to the bottom of the mountain and a bus service began to and from the high school at Southport, giving local families an alternative to sending their children to boarding school.

Through a state government grant, the Albert and Beaudesert councils were able to seal their sections of the road and in 1964, the Tamborine-Oxenford Road was gazetted a main road.

The official name was not widely-used however. Locals had already dubbed the carriageway the Do It Yourself Road, a name that stuck for many years on the mountain and is still used by old timers today.