Anzac Day 2020: How Tate family lost their youngest son during World War I

A southeast Queensland couple received a letter telling them their oldest son was dead. After mourning him for a month they got a second letter saying he was very much alive, but their youngest son had died on the bloody fields of Passchendaele.

History

Don't miss out on the headlines from History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOR weeks in late 1917, Edward Tate mourned the loss of his eldest son to the senseless bloodshed of World War I Europe.

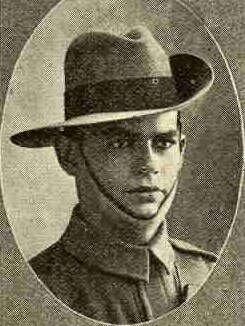

Frederick Royal Tate had defied medical opinion to fight on the frontline and saw service in both Egypt and France. Then a telegram arrived at his family’s front door in Chester Street, Brisbane.

He was dead. Age 23.

Or so was the official line.

What his father, draper Edward and mother Isabel did not know was that Frederick was very much alive, holed up in Colchester General Military Hospital in England suffering from mild heart troubles.

It was his younger brother who had died.

In the course of a month the Tates would gain a son only to tragically lose another.

For 102 years the body of Errol Bannister Tate has rested under a white stone memorial in Belgium, near the bloody and muddy fields of Passchendaele.

For the first time, here is the story of a teenage assistant draper few knew existed, the frantic search by his parents for answers, and the discovery of war documents that remained hidden in archives for almost 100 years.

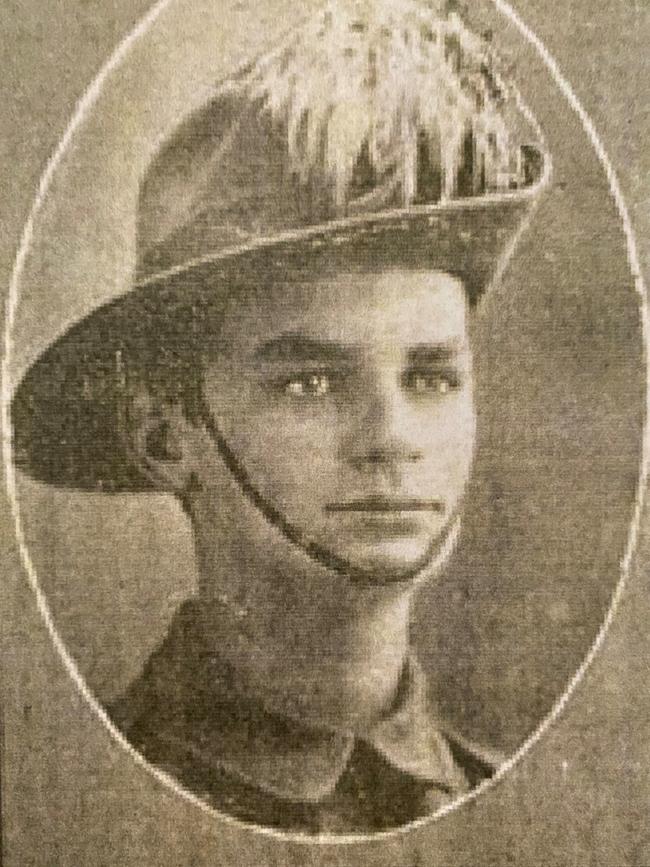

Just 17 years old, having given a false birthdate so he could serve, Errol had given his life for king and country.

No photographs of the young man are known to survive and all who knew him have long since died.

Private Tate’s story lay dormant until late 2017, just weeks after the 100th anniversary of his death when the letters from his family to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were rediscovered by his great nephew – Gold Coast Mayor Tom Tate.

Cr Tate is a descendant of Frederick and Errol’s brother Ernest, also a World War I veteran, and never knew of his uncle.

But while recovering from bowel cancer surgery he decided to research his family’s history and discovered the tragic story of the Tate brothers.

Speaking for the first time about the findings, an emotional Cr Tate said: “When I was young I’d always ask Pop about his days in the army and I always got very little because my Nan said it was something he did not want to relive and I respected that. He was old school and very strict.

“When I began researching I found out Pop had a young brother who had died and found the letters of my great-grandfather, Edward Tate.

“I don’t pretend to know how he felt, I can only see his handwriting but it affected me enormously.

“It is just heartbreaking to read and when we are allowed to travel again, I will go to his grave in Belgium and lay a wreath in tribute.”

Frederick was a baker who joined up in Brisbane on August 22, 1914, just three weeks after the beginning of World War I.

But upon arriving in Egypt he rapidly fell ill and was hospitalised in Ras-El-Tin hospital, Alexandria.

Initially diagnosed with bronchitis, he was found to have myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle.

After 75 days in hospital he was released on November 13, 1915, and sent back to Australia, deemed medically unfit.

Back in Queensland, Frederick found life different. His younger brother, Ernest Murray Tate, had enlisted the previous July and embarked for England with the 2nd Light Horse Regiment.

Born in 1897, Ernest Tate was two years into a stint as a draper’s assistant at Patterson Bros in Brisbane when he joined the AIF.

Despite multiple hospital stays for a range of conditions, Ernest was promoted to corporal before being classed as medically unfit in October 1918, just a month before the war’s end.

The youngest of the three brothers, Errol Bannister Tate, joined up on April 6, 1916, just three weeks before the first Anzac Day ceremonies were held.

About that time, Frederick defied medical opinion and re-enlisted.

It would be just over a year that Edward and Isabel would receive news he had been killed in combat in October 1917. It was meant to be Errol's name.

Errol, who before the war had worked as a draper, was not a tall man, standing at just five foot five inches (165cm). He had brown hair and blue eyes.

The larrikin, who had been forced to forfeit four days pay for an unsanctioned 36-hour holiday in England days before embarking for Europe, was killed in action in Belgium on October 7, 1917, during the Battle of Passchendaele, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres.

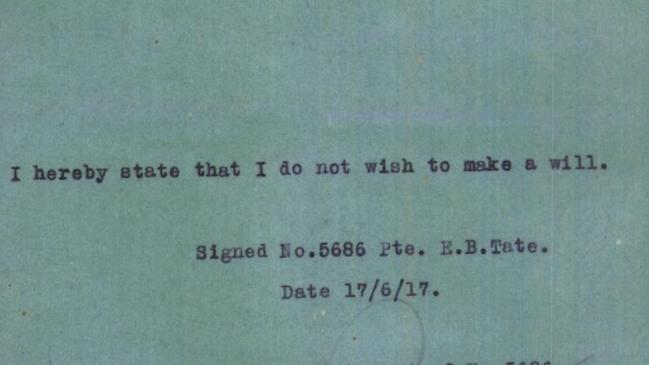

He left behind no will.

The Tates were devastated at the loss of their youngest boy and urgently wrote to the AIF seeking answers.

In newly uncovered letters, their grief is laid bare.

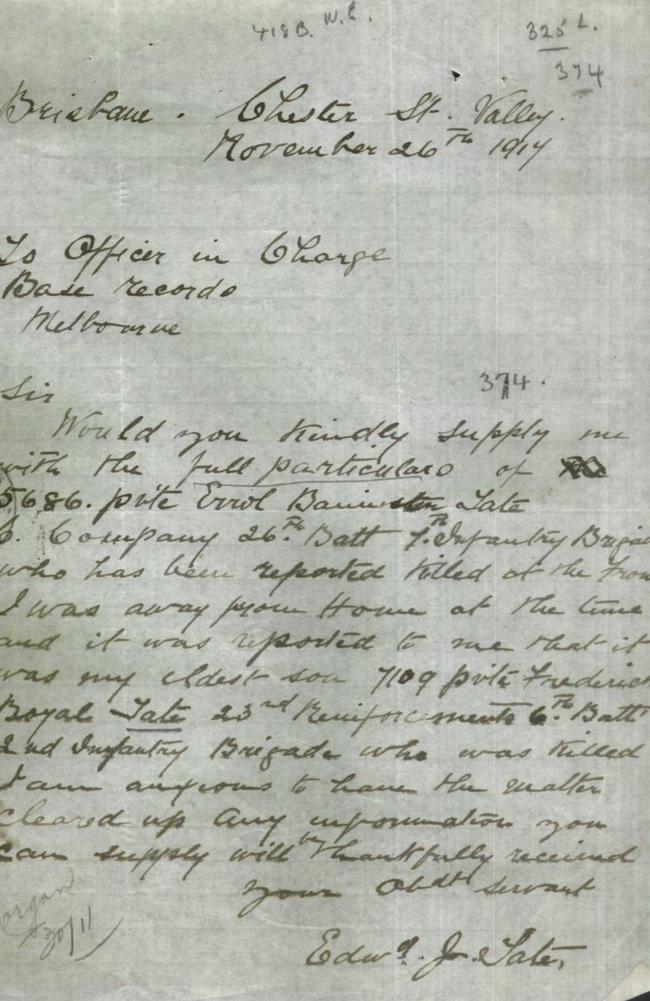

“Dear Sir. Would you kindly supply me with the full particulars about Errol Tate who has been reported killed at the front,” Edward Tate wrote on November 26, 1917.

“I was away from home at the time and it was reported to me that it was my older son Frederick who was killed.

“I am anxious to have the matter cleared up and any information you can supply will be thankfully received. Your loyal servant, Edward Tate.”

A second letter, now lost, asked for any further information.

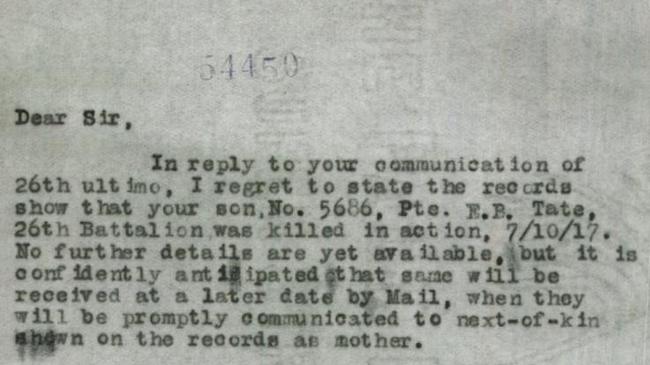

On December 7, 1917, the Tate family received a letter officially informing them of their son’s death

“I regret to state the records show your Son No. 5686 Pte E.B Tate, 26th Battalion was killed in action, 7/10/17. No further details are yet available,” the letter said.

Edward Tate sent a telegram to the Melbourne-based records office on December 17, 1917, asking for more information

“No reply (to) my two letters, very anxious. EJ Tate,” the telegram said.

No information was forthcoming.

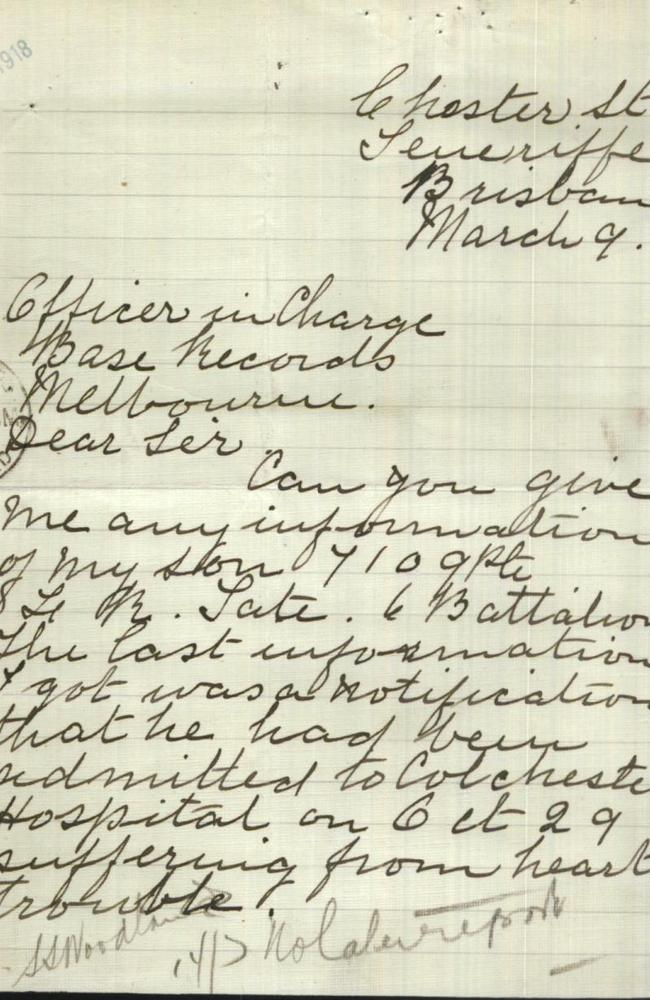

Three months later, on March 9, 1918, Isabel Tate wrote to the records office requesting an update on both Frederick’s health and Errol’s belongings.

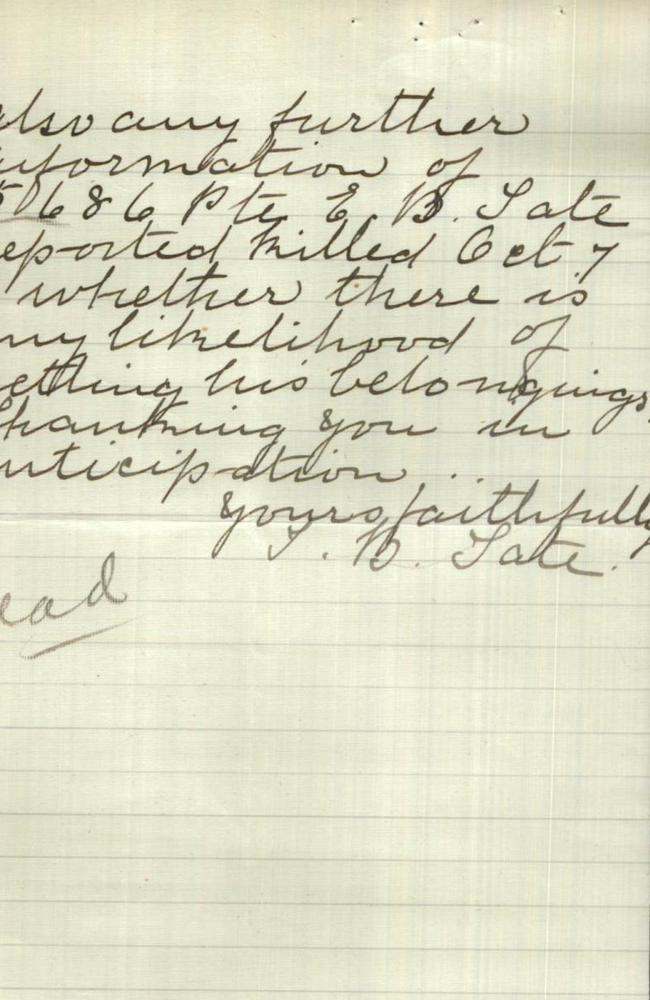

“Also, any further information of Errol Tate reported killed October 7, 1917 and any likelihood of getting his belongings,” she wrote.

Ten days later she received a response.

“In reply to your communication of the 9th instant I have to state, so far no personal effects of your son, the late No. 5686 Private E.B. Tate, 26th Battalion, have passed through this branch, although a heavy shipment is in the course of being dealt with.”

War records reveal the personal effects of the late Errol Tate were never recovered.

A memorial tombstone was laid for him at Ypres.

Ernest Tate returned to Australia in 1919 after the end of the war on November 11, 1918, and was medically discharged.

He worked as building inspector in Sydney for many years before retiring and dying in 1988.

Throughout his life, he never spoke with his family of his brother’s death or his service.

Like many veterans, it was simply too painful.