Behind-the-scenes at Gold Coast’s Allambe Memorial Park crematorium

IT’S the post-death process most of us avoid ever learning about but behind-the-scenes at one of the Gold Coast’s busiest crematoriums is morbidly fascinating. From turning the human form to ashes to the antics of grief-stricken loved ones — the stories are riveting. WARNING: GRAPHIC

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WARNING: Graphic content

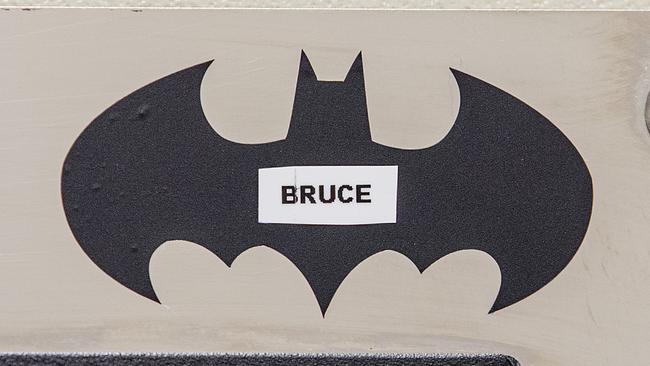

Dubbed ‘Bruce’ and ‘Wayne’, they’re the Batmen of the Gold Coast death industry.

But Bruce and Wayne are not people. They’re two $750,000, state-of-the-art machines that heat up to 1000C and cremate nearly 2000 of the 3400 Gold Coasters who die every year.

The cremation process is one most people shy away from ever wanting to know about.

But a peek behind-the-scenes at one of the Gold Coast’s busiest crematoriums — Allambe Memorial Park at Nerang — is morbidly fascinating.

Chief cremator operator Steve Claggett has arguably one of the most confronting jobs in the city but he’s passionate about ensuring the recently deceased are treated with the sensitivity they deserve as they complete their journey from human form to ashes.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE GOLD COAST BULLETIN

“We do it very professionally and with empathy, I treat the people how I’d want my loved ones treated,” Mr Claggett says as he proudly tends to the two machines that he bestowed the superhero names on.

“My wife even wants me to cremate her when it comes the time.

“We get everyone from war heroes and famous people through to bikies. They are all treated the same.

“Baby cremations are the hardest. I’ve had times when it’s stopped me in my tracks.”

Thursday and Fridays are usually the busiest days for the crematorium because less funerals are planned for Monday.

The team can process up to 14 deceased a day but will ramp up operation hours when required during peak times like the height of summer, when more people tend to pass away.

THE PREPARATION:

The cremation process puts into perspective just how fragile our bodies are.

In a matter of minutes, inside a chamber heated to up to 1000C, the human form literally evaporates into thin air.

Mr Claggett starts at about 5am Monday through to Saturday and takes delivery of up to 14 bodies a day from funeral directors.

The cremators take an hour to fire up but even after being turned off overnight, they’re still insufferably hot when Mr Claggett opens the furnace door.

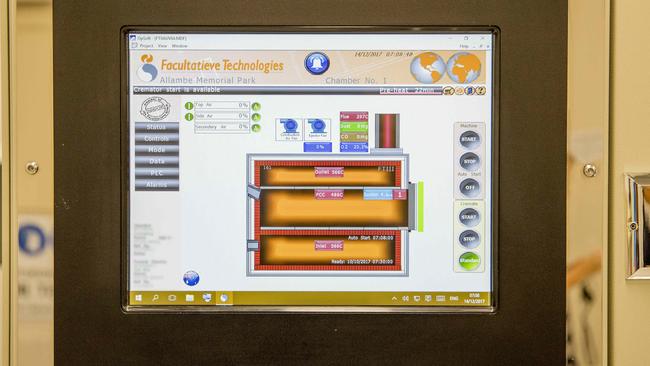

Today, it only takes 15 minutes to reach the starting temperature of 770C.

Only one body goes through each cremator at a time. The rest of his late clients are stored in a large refrigerator that holds up to six coffins.

Mr Claggett never physically sights the people with whom he’s charged with cremating.

He’s provided crucial paperwork about the person, including their name, age, weight and contents of the coffin, but the coffin lid always stays shut.

Batteries, bottles, cans, pacemakers and more than one stuffed toy are banned from the cremator because of the highly-flammable and explosive nature of the items.

“I’ve had people ask can he take his phone in the coffin and you say yes but not with the battery,” says Mr Claggett.

“We had one occasion where a family filled the coffin with 20-30 plush toys which are highly flammable and the temperature went through the roof.

“And we had another person request if their loved one could be cremated in his wet suit and we had to say no because the rubber may not burn away.

“People have put golf clubs, tattoo guns in coffins, we quite often find burnt coins in the ashes”.

Mr Claggett wears personal protective equipment including a fire-retardant shirt, full shield face mask, safety glasses and gloves as he loads a coffin on a charge bier, which is like a large trolley that places the casket into the cremation chamber.

The coffin name plate is transferred to a ledge at the front of the cremator and follows the body right through the various stages of the cremation to ensure traceability.

THE PROCESS:

The caskets go in headfirst — a change from the previous method of going in feet first — because the head and shoulders are the bulkiest part of the body.

They go straight under the super-hot gas jets.

Once the door is shut, Mr Claggett programs the computer and the cremation process starts while he monitors its progress through a peephole in the door.

The whole cremation process takes between 1 to 1.5 hours for an average person.

Oversized bodies can take up to three hours. Mr Claggett says the biggest person he’s cremated has weighed 270kg, coffin included, and it took 3.5 hours.

“But generally if someone weighs more than 250kg, it’s considered too heavy for the charge bier and they have to go to burial,” he says.

“Younger people tend to have more muscle mass and will burn a bit slower compared to an older person.”

The coffin catches fire shortly after entering the chamber and within 10 minutes it has collapsed.

Skin, muscles and tendons start melting away quickly. The heart and brain are the last organs to go — all literally evaporating into thin air.

By the 50 minute mark only calcified bones remain.

During the process, air from the cremation chamber goes into a second chamber through suction where it is ‘burnt’ again to remove any residual matter before the clean air is released into the atmosphere by a flue.

Once it has finished, Mr Claggett rakes the red-hot ashes — which now weigh between 5-8kg — into a pit where they cool for an hour while being blasted with compressed air.

It’s a revolving door — the next coffin is then loaded into the cremation chamber.

Among the ashes, some items survive including replacement body parts like hips, knees and screws.

They’re sent for recycling and the money is donated to charity.

“We’ve had a couple of families request a titanium rod from their loved one’s leg … people are making jewellery out of it,” explains Mr Claggett.

“Sometime we get rings, watch frames and underwires from bras that survive the cremation process.”

Once cooled, the remains are put in an ash processor which grinds up the bones.

It only takes two minutes.

From there, the ashes go in a PVC container marked with the person’s name and registered cremation number before being placed in a storage room with hundreds of other ashes waiting to be collected.

THE HEARTBREAK:

From stoic and strong fathers of stillborn babies to grief-stricken wives and slightly strange relatives, Mr Claggett has seen all kinds of grief.

Some families — often Sikhs, Buddhists or people of Asian heritage — choose to witness the cremation and Mr Claggett dresses in a suit to ensure the family are shown the utmost respect.

They chant mantras to ensure safe passage and believe fire is purifying and a gateway to the afterlife.

They can watch through a glass window from a separate room or choose to be on the crematorium floor under strict supervision from several staff.

Allambe Memorial Gardens family services manager Gaylene Adam knows the risks.

“About 15 years ago, at another crematorium, I’ve had someone try to climb in the cremator after their loved one. It’s hard when they are so overcome with grief,” she says.

Mr Claggett will do whatever the family needs to help with the healing process.

“There was a stillborn baby and after the funeral service the father asked ‘what happens now?’ He was told he could bring his baby to the crematorium, so he came and presented the baby’s coffin to me. We got a nice email from him later saying it really helped him through the process,” he says.

“One family requested Bridge over Troubled Water be played as the coffin went in, which I was happy to do.

“A man asked me if he could press the button to the machine when his loved one was being cremated. I couldn’t allow him do that but let him put his hand on my shoulder as I pressed the button.

“The next minute I turned around and there was a conga line of people behind me with their hands on the shoulder of the person in front of them.”

Japanese people will often attend the crematorium and do a ‘bone pick’ from their loved one’s remains.

“They gather around with chopsticks and remove the bone pieces and put them in a ceramic container. They’re looking for the voice box bone which looks like a Buddha,” explains Mrs Adam.

There’s plenty of moments the love of the deceased is even apparent from outside the casket.

“I’ve had a coffin that’s had messages written all over it from family and I’ll tap the coffin and say ‘you’re a lucky girl to have had so much love’.

“We get coffins with themes, I had to burn a Batman one which hurt a bit”.

THE UNLOVED:

Nearly 80 per cent of all people who die are cremated these days as society moves away from traditional burials.

In recent years the number of cremations at Allambe has jumped from 1400 to about 1900 each year.

But among those are the sad cases where the person has not had a funeral service or does not have family willing to take their ashes.

“We get people who have not had a service all the time … we could have 16 one day and four the next,” says Mrs Adam.

“A homeless man had been in the freezer for 12 months before next of kin could be found.

“Sometimes we’ll get decomposing bodies too.”

In the storage room, some ashes have lain uncollected for up to five years because of family disputes or no one wanting them.

Allambe attempts to communicate with the family and after 12 months will send a registered letter advising they may dispose of the ashes.

“Often families will say ‘we’re just not ready’ and we’ll continue to hold the ashes until they are ready to decide,” says Mrs Adam.

“Some people just don’t pick up the ashes.”

She said people do say things like ‘he was a horrible man, I don’t want anything to do with him’.

“And that’s really sad,” says Mrs Adam.

If the ashes remain unclaimed and all efforts are exhausted, they are scattered in Allambe Memorial Gardens.