FLASHBACK: The inside story of worst Gold Coast shark attack after Kirra surfer killed on Greenmount Beach

Two dead and the third emerging a hero after swimming out to the deep in an effort to save his mates - after a surfer's tragic death on Greenmount beach, the Bulletin revisits the city's worst shark attack more than 80 years on.

Beaches & Fishing

Don't miss out on the headlines from Beaches & Fishing. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY had just marched on the beach, celebrated the opening of the Kirra pavilion. Twelve months later, these lifesaving mates wave their arms for help, as the grey rolling surf turned bloody red.

Two of them will die and the third emerge a hero, swimming out to the deep despite the pleas of his brother to stay safe inshore.

For the first time, the gripping full story of the first recorded — and most deadly — shark attack in Queensland can be told as the 80th anniversary approaches.

After speaking to witnesses and families, obtaining police statements and Kirra surf club records, the Gold Coast Bulletin has pieced together what really happened that fateful day in 1937, before shark nets, when monsters lurked off two reefs on the Coast’s southern end.

Previous reports suggested 22-year-old Joe Doniger was motivated to save his 17-year-old brother Gordon. But his own account shows he risked his life for two Kirra mates.

Was there more than one shark circling them? Did hunters catch the right monster?

KIRRA CELEBRATES A NEW SURF LIFESAVING HOME

It starts with a drowning, a respected young bloke is lost and the community arranges a town meeting and civic leaders call for volunteers. Kirra in 1916 becomes the Coast’s second surf club.

“A number put up their hand. They basically had to train themselves. The only other club at that time was Greenmount,” Kirra life member, historian and lawyer Peter Kelly says.

Twenty years later and a celebration like no other. Dignitaries arrive for opening of the new Kirra Pavilion. Someone after the march past says “you would not see a finer body of men”.

Gordon Doniger is in the junior surf handicap, older brother Joe competes in surf races, always out there with mates Jack Brinkley and Norman Girvan.

John Cunningham, who would grow to become one of the border’s most respected and much loved lifesavers, looked up to Joe. He had yet to turn five.

The broad shoulders stacked on top of the “swimmer’s legs” carried an aura — having a bloke like Joe around meant you would be safe in the surf.

“He was always muscly — my father thought the world of him, used to say he was a hard worker. He was very strong for his size. He wasn’t a big man.”

THE KNOCKOFF SWIM

A storm is building out to sea, the poor weather reflected in the water’s murkiness. About 5.15pm on October 27, 1937 Gordon and Norman Girvan are joking as they enter the surf.

Joe parks his truck, changes into his togs. They are 150m out as he stands on the first sandbank.

Gordon and Girvan joke about sharks. Gordon spots a “shoot”, swims about five metres away, urges his mate to join him.

“Quick, Don, shark’s got me,” Girvan says.

Gordon suspects he’s joking. Girvan raises his arm. The blood is spilling into the surf.

Gordon reaches back for him. “I’m coming Blue,” he says.

THE SECOND ATTACK

About 10 metres away is Jack Brinkley. “For God’s sake Jack,” Gordon says. “Come and give us a hand with Blue and get this thing away.”

He watches Brinkley, sees he is struggling, kicking hard.

He grabs Girvan by the arm which hangs by a bit of flesh. “It won’t let me go,” Girvan says. “It’s got my leg.”

The shark is shaking Girvan, until Gordon loses his grasp. He feels it brush his thigh, sees it rise to the surface.

Girvan is about to be lost. “I’m gone. Goodbye,” he says to Gordon.

Gordon puts his head down, swims fast. The shark is under him. He pushes it away, his hands grip the fin.

Joe is swimming towards him, across a deep 40m-wide gutter. Gordon passes him on the wave.

“Don’t go out there, Joe. It’s the biggest shark you have seen in your life.”

BLOODY AND BRAVE

Joe recalls standing ankle deep in water, he later tells police, when the three of them wave their arms, about 70m from the shore.

“I heard my brother calling Brinkley for assistance. I saw a swirl in the water become discoloured and red with blood.”

A second shark is circling Brinkley.

“I know that there are two sharks because the shark that I first saw was bigger than the shark which attacked Brinkley,” Joe says.

Girvan disappears as Gordon finds the wave to the beach. Joe is within five metres of Brinkley. “Hurry up, Joe, for God’s sake get me out of this.”

A shark strikes again. Brinkley’s left arm below the shoulder is almost severed. Joe gets a glimpse of the shark. It must be at least 2.5m long.

Time does not allow him the luxury of fear. “All I knew was Brinkley and I had to get out of the water. The beach was all I thought of.”

Brinkley groans as he drags him on to the sand. “Can I take it,” he says. His voice is triumphant. Lifesavers apply a tourniquet.

He turns to Joe. “If I hadn’t turned back for Blue (Girvan) it wouldn’t have got me.”

THE SEARCH FOR A KILLER

They start searching for Girvan’s body. Lifesaver Alf Kilburn pulls back on his surf ski after a shark at the first line of breakers circles the edge of the blood line.

The club’s boat Arakoon is launched as parts of Girvan’s body wash up between Bilinga and Tugun.

Brinkley is rushed to the Tweed Hospital. “It has come at last. I knew something was going to happen this week,” he tells mates.

His arm is amputated. Lifesavers arrive to give blood. His chances of survival appear strong.

He was waiting to announce that the previous day he asked a local girl, Thelma Hastie, to marry him, and she agreed.

Just before 3.15am, after talking to those around his hospital bed, he collapses and dies.

Joe plays down his role. “Girvan and Brinkley were my mates, they would have done the same for me — Brink was my best pal,” he tells reporters.

Later in the morning, four baits are set for the sharks. The 44 gallon floating drums with chains have legs of lamb attached to hooks. On Kirra Hill, a crowd builds for the kill.

MONSTER AT THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA

About 10am a rush of water around a buoy before it disappears. From the hill, a dark patch is visible on the sandy floor.

The crew on Arakoon secure the monster with grappling irons. As it surfaces, the killer appears dead before it lunges at the lifesavers and spits out the hook.

Jack Gordon raises a .303 rifle and fires off four bullets. On the beach everyone cheers as a chain is placed on the shark’s tail.

They are close enough to see the dark faded vertical stripes across its rump and tail. The Tiger is 3.6m long with a girth of 1.9m and weighs 385 kilograms.

John Cunningham stands by his father, eyes as big as beach balls. “Dad took me and it was a hell of shock. It’s mouth was open and had a big stick in it.

“It had a big effect on me. Dad shouldn’t have taken me. I didn’t fully understand I was looking at a man-eater. They cut it open.”

Up at the boat shed, a doctor finds human remains He takes notes for the Coroner — a left lower leg, right hand and forearm, bones of a right shoulder and upper arm, bones of a left arm.

Two more sharks are sighted. A private plane is hired and more baits put out. The crowd disappears. The beach is no longer their friend.

“They (the lifesavers) didn’t go in the next week. It had an enormous effect (on the community),” Mr Cunningham says.

THE TWEED RIVER RESCUE

The Girvan family purchase a coffin aware they will never retrieve the body of their son. More than 200 people attend the funerals.

A special plaque is placed in Tweed Heads cemetery. Girvan and Brinkley are resting together.

Joe collapses in a Tweed Heads street, is treated at the hospital. The weight on those shoulders — he walks silently ahead taking the load by himself.

He steps forward alone and accepts honours as he and Brinkley receive surf lifesaving’s highest awards for bravery — the Royal Humane Society Gold Medal and the Silver Medallion.

Nine months pass, Joe is in his truck around Duranbah. The motor launch Penguin capsizes in the cyclonic winds on the Tweed Bar. Four of the crew escape.

He swims out into the rolling bar, retrieves the captain, tries to resuscitate him. Two doctors and ambulance officers arrive and are unable to revive Sam Sess.

THE IRONMAN

Club historian Peter Kelly pauses when asked about Joe’s legacy.

The Government, on the back of these publicised rescues, reached out to clubs and provided improved subsidies, Mr Kelly replies.

Kirra would suffer more wounds. Five members died during the Second World War.

“Even though the country was consumed by the effects of the war, Joe Doniger’s heroics of the day were never forgotten.”

Neither was Girvan or Brinkley. In 1990, the ashes of Thelma Hastie were spread where her fiancee was struck by the shark. Heartbroken, she never married. Five years later they scattered Joe’s in the surf.

All that is left are black and white photographs, a framed award. The best of them showing Joe driving his truck, his son George with a big blond fringe smiles from the back.

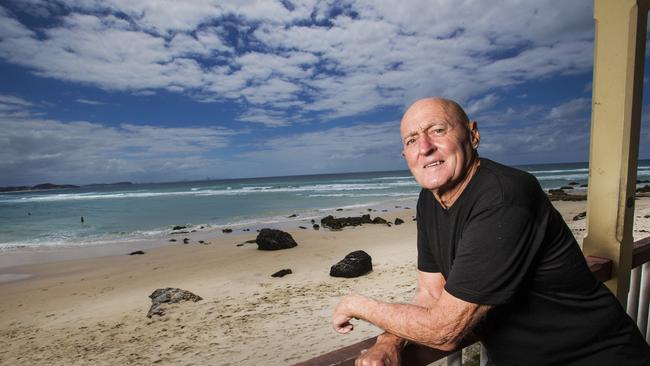

The talkative son, who with Mick Veivers became rugby league’s top TV commentary team in the 1970s, understands his late father’s silence. From others, he has learned about “the ironman”.

“He never talked about it,” George says. “He told me — ‘I was a lifesaver. They were my mates. I had to do it’.”

•On October 28, from 4-6pm at the Kirra Surf Club’s Supporters Bistro, a celebration will be held for the 80th anniversary of the bravery of Joe Doniger.