Folk music hero Jeremy Marou on the terrifying impact of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands

Folk music hero Jeremy Marou tells of the devastating issue his family is facing and what needs to change.

Music

Don't miss out on the headlines from Music. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are cautioned the following story contains images of deceased persons.

Jeremy Marou has walked in two worlds for his 40 years.

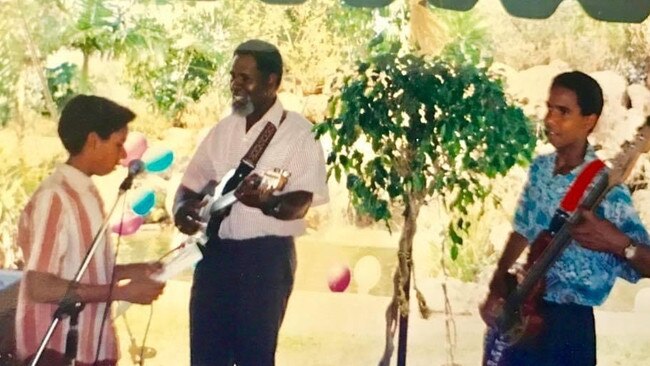

The Busby Marou musician, who sparks magic with his fingers on a guitar, grew up learning the cultural songs of his father Segar who grew up on Mer Island (formerly Murray Island) in the Torres Strait.

He honed the impressive skills he would pair with his mate Tom Busby’s expressive voice as a young churchgoer in Rockhampton, where his father settled in his 20s and brought up his family.

Father and son would play together often at church or family gatherings. Even if he hadn’t formed his award-winning, chart-topping blues and roots duo with Busby, Marou was destined to spend his life playing music.

“Music for me is a cultural thing. You go anywhere in the Torres Strait Islands and everyone sings, everyone plays an instrument, mainly the guitar,” he says.

“So I would have played music anyway, whether it was sitting at home with the kids or at a pub every Friday night.”

His two musical worlds collide each year with the Coming of The Light festival, known as Keriba Lagaw Buiya in language.

Marou explains the July 1 celebration is the biggest day of the year on the cultural calendar for Torres Strait Islanders, marking the peaceful arrival of representatives from the London Missionary Society on Erub Island accompanied by South Sea Islander evangelists and teachers.

“Everyone north of Cooktown celebrates the Coming of the Light, the first time they ever saw white people because they came across with Bibles. Their first interaction with Europeans was friendly,” he says.

“Anywhere south (in Australia) was different because Europeans came across and pillaged.”

Another significant date of his cultural calendar is the Cooktown Discovery Festival which marks the arrival of Captain Cook and the Endeavour at the tribal estate then known as Waymburr.

Cook and his crew of 86 spent seven weeks there from June 10, 1770, waiting for perfect sailing conditions to head back out to sea as the Endeavour had been damaged after hitting the Great Barrier Reef.

They had fortuitously landed in a neutral zone of Waymburr where 32 clan lands of the Guugu Yimithirr tribal nations would come together for cultural ceremonies and mediations. By law no blood was to be spilt on the land.

“Cooktown do a big festival every year, which we played at last year, that celebrates the journals of Captain Cook,” Marou says.

“It’s amazing that not many Australians know the diversity of stories of how white man came across. Everyone thinks every story is bad but it’s not, you know. I try to tell some good stories.”

Marou and his siblings were brought up in Rockhampton. His father died of a sudden heart attack on the local touch football field when Jeremy was 19. The musician also suffered a heart attack on the same field six years ago. Surgeons found Marou had exactly the same blockage in the same artery as his dad.

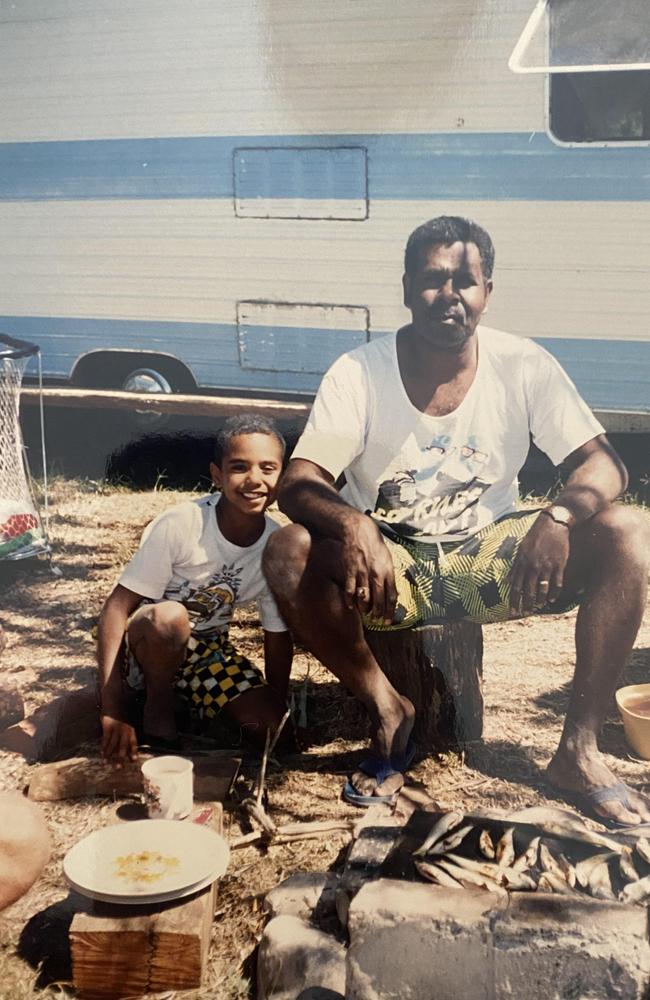

But before he died, Serga would take his children back to Mer Island to visit family and reconnect with culture.

He has taken his own children Miles, 19, Zahirah, 15, Pere, 14 and six-year-old Ziggy to his father’s homeland but it’s tough to make it a regular trip as flights are prohibitively expensive and the ferry journey takes three days.

“We play the cultural songs around the house every now and again, not that often, and that’s probably my fault,” he says.

“But the kids definitely know them. And the beauty of that is they feel that culture. When I take the kids back there from time to time, they still sing the same songs and do the same dances. When they’re back on the island, they know they’re not losing the cultural aspect of it all.”

But Marou, the grand-nephew of land rights advocate Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo, and the Torres Straits peoples are in the fight of their lives to save the precious lands where their culture has thrived for tens of thousands of years. They face the terrifying prospect of becoming Australia’s first climate refugees.

When Marou and Busby travelled to Mer Island in 2019 to record a video for their single Naba Norem – meaning “let’s go to the reef” in the Meriam language – family showed him the impacts of rising sea levels on the islands. He has returned since to further awareness of the Torres Strait Islanders’ plight.

“It is scary because they could possibly be Australia’s first climate refugees and no one is talking about it,” he said.

“The water is already lapping over people’s homes and gravesites, some of these islands will be totally gone and where do they go? It’s such a beautiful lifestyle and sea levels are rising and threatening their existence.

“Even when I go back to my island, the uncles point out where the beach used to be and now it’s under water.”

For that reason, to bring the climate crisis threatening the Torres Strait Islands to the urgent attention of the nation, Marou supports the Yes vote in the upcoming Voice to Parliament referendum.

As Busby Marou takes their latest album Blood Red on tour around the country, he said he would prefer Australia had first negotiated a treaty with First Nations peoples, but the Voice to Parliament was imperative to improve the health and prosperity of his family.

“As a band we do try to stay apolitical but this is important. I think the conversation we should be having is why we are the only country in the world without a treaty. But I’m certainly going to vote yes,” he says.

“The only thing going for blackfellas in this country is native title. And that was created to keep us at bay.

“My grandfather fought for native title and won so we got back the land, and I have land on Murray (Mer) Island but I can’t do nothing with it. I can’t put a shop on it, or a tourism venture, where there is some of the best fishing in Australia, I can’t do anything with it that makes me money.

“And that’s as far as we’ve come in all these years, We need something, and if the Yes vote doesn’t happen, it will have a very negative impact on our people.”

For all Busby Marou tour dates and tickets https://www.busbymarou.com/#tour

More Coverage

Originally published as Folk music hero Jeremy Marou on the terrifying impact of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands