‘True miracle’: How an Aboriginal artist went from Alice creek bed to Buckingham Palace

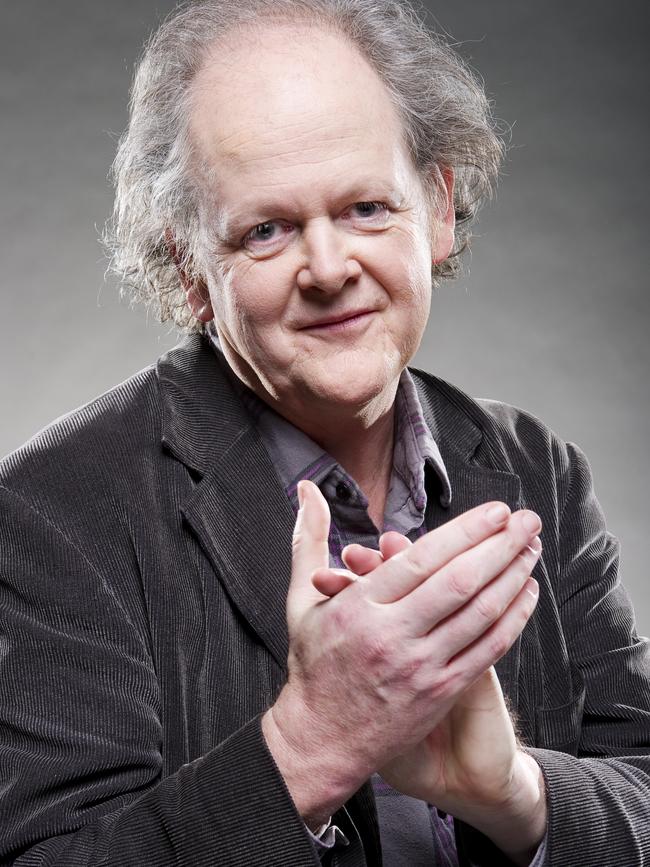

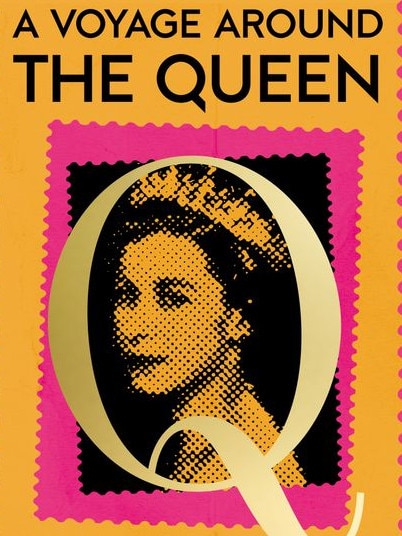

The most original biography yet of Queen Elizabeth II, Craig Brown’s A Voyage Around The Queen, contains dozens of little-known anecdotes – including the time an Australian artist found himself at Buckingham Palace.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Rebecca Hossack is a London art dealer who specialises in Aboriginal art. An Australian by birth, she set up her first gallery in the city’s Windmill Street in 1988.

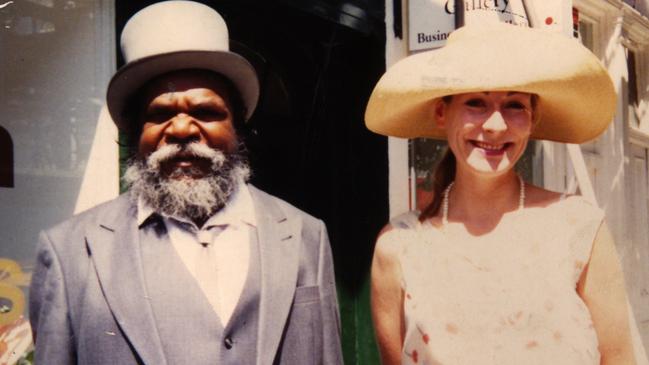

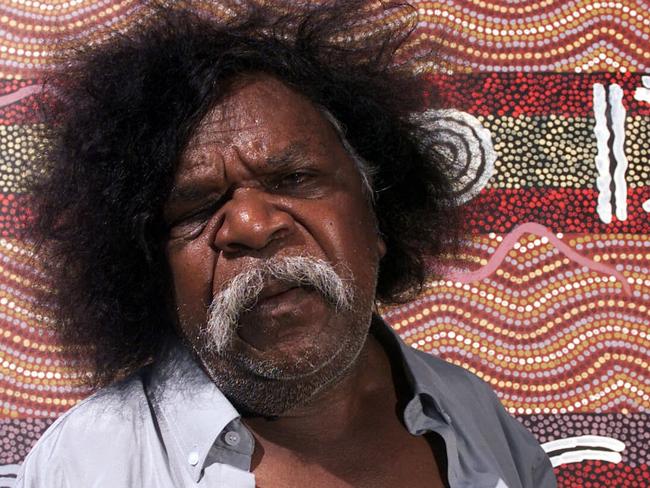

‘When I first met the Aboriginal artist Clifford Possum in the creek bed in Alice Springs in 1989, I asked him if he’d like to have a show in London, and his first response was: “Queen”.

‘And so I said, “Of course, when you come to London, you can meet the Queen.” But my main thought was, “Brilliant: this great Aboriginal artist is going to come to London to have an exhibition at my gallery.” ‘So, several months later, I went to pick him up from Heathrow,

and there he was in his cowboy hat. He didn’t really speak much English – though he spoke six Aboriginal languages. He was a very clever man. But almost the first thing he said to me was “Queen”. Of course I’d forgotten my promise that he could meet the Queen, but I thought, well, we’ll just drive him past Buckingham Palace. So we drove past the palace, and there it was, the flag flying.

‘I said, “Clifford, that’s where the Queen lives.” And he went, “In, go in!” And then I realised he had told everyone in Alice Springs that he was going to London to meet the Queen. (It turned out he’d even been photographed for the front page of the Alice Springs Advertiser with the headline “Clifford Flies to London to Meet the Queen”.)

‘I didn’t know what to do. I thought, “What have I done?” I have been yet another white person who has betrayed the trust of the Aboriginal people. I have promised something, and entirely failed to deliver it.

‘So I rang up Malcolm Williamson, who was Master of the Queen’s Music at the time, and an Australian, and he said, “Well, I’ll see if I can get you an invitation to a Royal garden party, but I don’t think he can meet her.” And I thought, well, perhaps that’ll do. I still felt terrible,

though.

‘That night it was the private view of Clifford’s exhibition at my gallery in Fitzrovia. The gallery was crowded with people. It was the first ever major Aboriginal art exhibition in London. It was a hot summer’s night, and this distinguished-looking man with a white

beard came in. It turned out he was Lord Harewood, and he was with his wife, who was an Australian musician. They’d seen the Aboriginal flag hanging outside the gallery as they’d been walking down Windmill Street, and they’d just popped in. They were amazed and impressed by Clifford’s pictures. We had some nice chat, and he asked why I seemed a little distracted. And I said, “I’ve done something so terrible. Clifford’s come to London expecting to meet the Queen, and he can’t. I’ve lied to him, and he’s going to lose so much face.”

‘He didn’t say anything to this. But the next morning, the telephone rang at 9 o’clock. It was Lord Harewood. He said, “I’ve spoken to my cousin, the Queen, and she would be delighted to meet you and Clifford at the Garden Party this afternoon.” I nearly dropped to the ground. In my whole life, that was the most extraordinary thing that ever happened. It was a true miracle.

‘So we had to go and hire Clifford a top hat and morning suit from Moss Bros. He put paintbrushes in his hatband, and he wore white tennis-shoes which he painted with a possum dreaming. He was so excited.

‘We went to Buckingham Palace and sat in some antechamber, and then we came down the steps into the garden, and all the people were behind ropes on either side; but somehow we were in the middle, and the Queen came up to us.

‘It was the most amazing moment. Clifford seemed to rise in stature, with his top hat. He was very dignified. He and the Queen had a conversation. It was extraordinary. I think he was the first Aboriginal to go to Buckingham Palace. He spoke to her and it was quite a long

conversation. I was astonished because, with me, it seemed he couldn’t really speak much English. But they were actually communicating. She had bush tobacco in her garden, which is called Pituri, and the Aboriginals chew it, and he noticed it and so she and he talked about

that. It was miraculous. The Queen maintained her very correct English and Clifford somehow picked up what she was saying, and responded. It was an encounter between two impressive people from very different worlds, conversing across this great divide.

‘Afterwards Clifford said to me it was his “Number One Day”.’

This is an edited extract from A Voyage Around The Queen by Craig Brown: available now, published by HarperCollins.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘True miracle’: How an Aboriginal artist went from Alice creek bed to Buckingham Palace