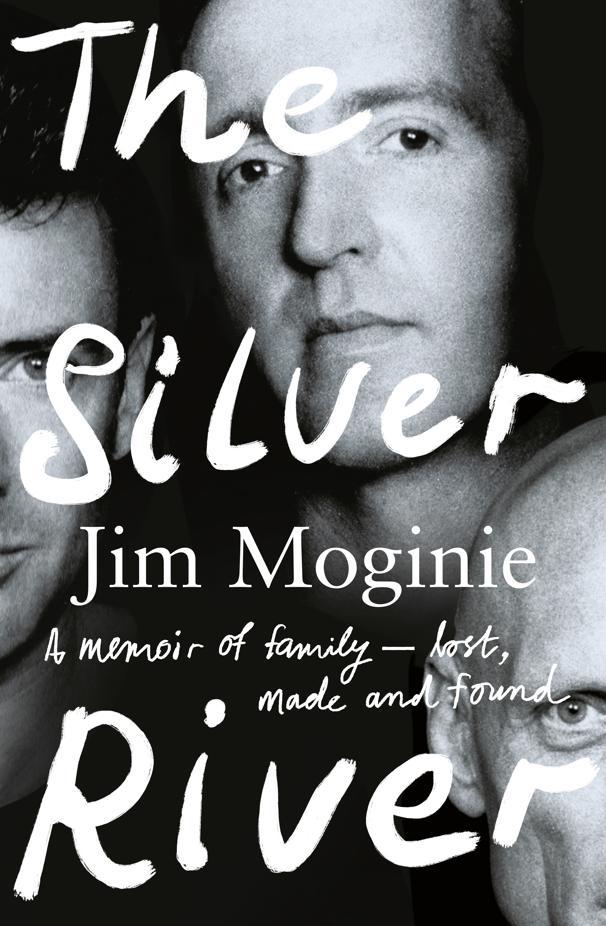

Surprise ending to Jim Moginie’s family search

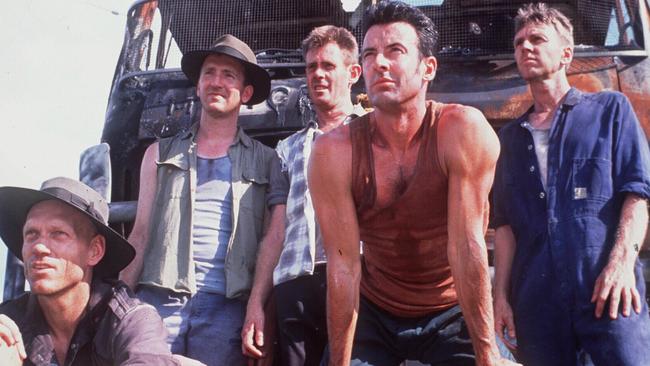

Midnight Oil’s Jim Moginie not only tells the story of the iconic Aussie band in The Silver River – he recalls discovering that he had been adopted and the long search for his birth family.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 2003 I sourced the medical charts of my birth. There was a Sydney address for my biological mother Susan Maloney, near Manly Lagoon. I drove down there and sat outside, soaking up the atmosphere in a rather desperate way 45 years later, looking for answers where there were none.

The trail was cold, the participants had moved on.

Sitting in the car, I tried to imagine what the hospital would have been like for her. Under no circumstances were mothers allowed to form bonds. Babies marked ‘FOR ADOPTION’, as I was, were hidden from them by a sheet and whisked away at birth. The nurses saying, ‘It’s for the best,’ while just trying to deal with the brutality of the situation.

I had been kept in hospital and bottle-fed for 19 days until I was deemed ‘Satisfactory, free of congenital defects and fit for discharge’. From there, the Benevolent Society records show I was taken to the Scarba House orphanage in Bondi, where I was kept from 5 June to 18 July 1956, before a home was found for me. Two months seems like a long time to have been left alone without a mother. It’s something I’m glad my own children didn’t experience.

I wrote him another letter on a Thursday and sent it off. The following Tuesday night, my kids and I were settling in for some TV when the phone rang.

A gruff voice spoke. ‘Hello. Is this Jim?’ A radio played talkback in the background.

‘Yeah.’

‘It’s Brian.’

‘Who …? Brian!’

‘I got your letter. So,’ he asked curtly, ‘what’s all this about?’

Tips from the Adoption Handbookkicked in. ‘I’m looking for Susan Maloney. I believe you knew her in Sydney in 1956. I wonder if you could put us in touch.’

‘Oh yeah. Why?’

I took a breath. ‘She’s my birth mother. I was adopted out in 1956.’

Silence for a few seconds. I could hear my heart beat and Brian’s radio.

‘Well now,’ he said, ‘I’m your father, and you’ve got five full-blooded brothers and sisters, and they’ve got eleven kids between them.’

I felt faint. I could hardly speak, but I heard myself say, ‘Can I meet up with you? I can come down to Canberra tomorrow.’.

He coughed. He didn’t sound too healthy.

‘Nah. I’ve got something to do. Don’t call me. I’ll call you.’

He hung up.

***

Brian did finally call a few weeks later. He sounded healthier. He’d been in hospital but was vague about the details. I organised to meet him at his home in the suburb of Rivett in Canberra.

I arrived in a quiet cul-de-sac. The house was more like a tiny cement hovel – government-issue besser block.

I knocked on the door. There was some coughing and shuffling.

I obliged, and when I returned we sat down to talk.

The place was small and sparsely furnished, clothes draped all over the room. It smelt of stale cigarettes. At the back was a screen door and a couple of broken chairs. We headed out there.

After Brian had lit up, he relaxed and said, ‘Yes, I’m your father.’

He said that he and my mother had never told another soul.

She’d gone to the family doctor when she found she was pregnant at 19. It was the 1950s, and being unmarried and with child in a Catholic community in a semi-rural town like Queanbeyan was no joke. The doctor admonished her. ‘This news will kill your mother. She has a heart condition; you must under no circumstances tell her. Now you listen to me, young lady. I’ll tell you what you are going to do …’

Marriage was the bedrock of society and babies were not supposed to be conceived outside it. You couldn’t even discuss it.

But ‘decency’ had a price. A whole wing of the Royal Women’s Hospital in Paddington was dedicated to the industry of delivering countless illegitimate children.

‘Your mother was christened Susan, but everyone called her Anne right from the start,’ said Brian. When she’d started to show at seven months, late in the piece as pregnancies go, Anne had travelled to her sister Kit’s place in Manly, the same house that I had sat outside in the car. Four days after the birth, Anne went home and returned to work the next day. It was a huge secret to wallpaper over, but that’s exactly what my birth parents and my Aunt Kit did. And then Brian and Anne went on to have five more children together: John, Janet, Paul, Dave and Susan.

I was reeling at all this information. I snapped a couple of photos of Brian and me together, the only photos I have with my birth father.

The shadows got longer and the cold came on, so we moved inside. There was a yellowing pine dresser collecting dust, with lots of family photos, but none were of Anne. A photo of my sister Susan, who looked the spitting image of my daughter. In all the faces there was a similarity to my own. They were all in groups, smiling and happy. The brothers looked kind of beefy, just like me.

Brian sat on the bed, ready to tell me more. He told me he was 67 years old. He started to get emotional. ‘We should never have given you away,’ he kept repeating. ‘I shouldn’t have left Anne. She was the love of my life. Everyone had mistresses in Canberra in those days – it was the seventies, you know?’

I tried to console him. ‘It’s okay, it’s just the way it is. It is what it is.’ It was the best I could manage. ‘We can’t change it. It just happened.’ I gave him a clumsy hug.

I wasn’t expecting this reaction, even though all the reading said ‘expect the unexpected’. Yet here I was dancing into this man’s life creating havoc. The father I’d been searching for was finally before me and was now weeping uncontrollably.

He said my mother had remarried and was living in Goulburn. He suggested that she was too vulnerable to receive any surprises and wouldn’t want to hear from the likes of me. End of subject.

It was sunset now. There was a sudden movement outside the window.

‘That’ll be Dave. He lives round the corner.’

The man who poked his head around the door looked so similar to me that I couldn’t breathe. It could have even been me. He stepped into the room holding a plate of food for his father and looked me up and down.

‘Jim, this is Dave,’ said Brian.

‘G’day, Dave,’ I said.

‘G’day,’ he said, staring dead at me. ‘Who is this bloke?’ was written all over his face. He looked bewildered and a little toey.

‘Christ, you should know him, Dave,’ said Brian. ‘He’s your brother.’

I gave Dave the unedited story. He sat shaking his head. ‘God, I never knew. Just … unbelievable.’

When I told him I had been in Midnight Oil, he said he’d seen us in 1983 at a benefit show at Penrith Oval called One for the Kids. ‘I didn’t even see you,’ he said.

I explained that was my spotlight avoidance syndrome, heard and not seen behind that bald fellow running around at the front of the stage distracting everyone.

Brian was enjoying himself as he listened and lit up a few more smokes.

‘I’d better call Janet,’ said Dave. In the photographs, Janet, the eldest sister, looked like the organiser of family events and was probably the key to meeting my mother.

He dialled and I could hear a lively youngish voice through the receiver. ‘Hi, Dave. How are you?’

‘Janet, are you sitting down?’

‘Yeah, no, well yeah. What is it?’

‘I’m with Dad, but there’s three of us here. There’s a bloke called Jim with us.’

‘Okay. Yeah?’

‘He’s our brother.’

I heard Janet say, ‘Our brother? Dave, have you been drinking?’

‘No, really. There’s a bloke called Jim here … He’s our brother.’

‘Oh, f**k off, Dave.’ Then there was a click. She’d hung up.

‘That went well,’ said Brian.

Minutes later the phone rang. It was Janet.

‘You’d better come over. And bring this Jim fellow with you.’

***

We headed to Janet’s. It was a smart house a good twenty minutes away.

A tall and lissom redhead waltzed to the door, smiling. My sister. She welcomed me in, and I met her husband, Andy. They couldn’t have been more friendly. My partner Suzy, who had been waiting at a hotel, arrived half an hour later and everyone warmed to each other straight away. A bottle was opened and there was lots of talk as we all tried to come to grips with this new reality.

We examined some old photographs including some of Brian and Anne’s wedding. I mentioned that the Child Welfare Act document indicated that Betty and Paul Moginie adopted me officially on 29 November 1956. On 1 December, two days later, Anne and Brian were married in St Gregory’s, Queanbeyan. In the wedding photos, they look radiant and happy.

Seeing Anne’s picture for the first time did something to me. ‘Is there a chance I could meet my mother?’ I asked.

A couple of ideas were bandied about, then Andy suggested, ‘Janet, myself, Dave and Susan will drive to Goulburn to see Anne tomorrow. You follow an hour behind. You’ll be on your way to Sydney anyway. If she wants to meet you, we’ll call you. If she doesn’t, just keep driving.’

Andy would meet Suzy and me at the Big Merino in Goulburn if I got the thumbs-up.

We were refuelling at Collector, about fifty kilometres out of Canberra, the next day when I got the call.

‘Come on down, Jim. She wants to meet you. See you at the Big Merino.’

This is an edited extract from The Silver River by Jim Moginie: available now, published by HarperCollins.

More Coverage

Originally published as Surprise ending to Jim Moginie’s family search