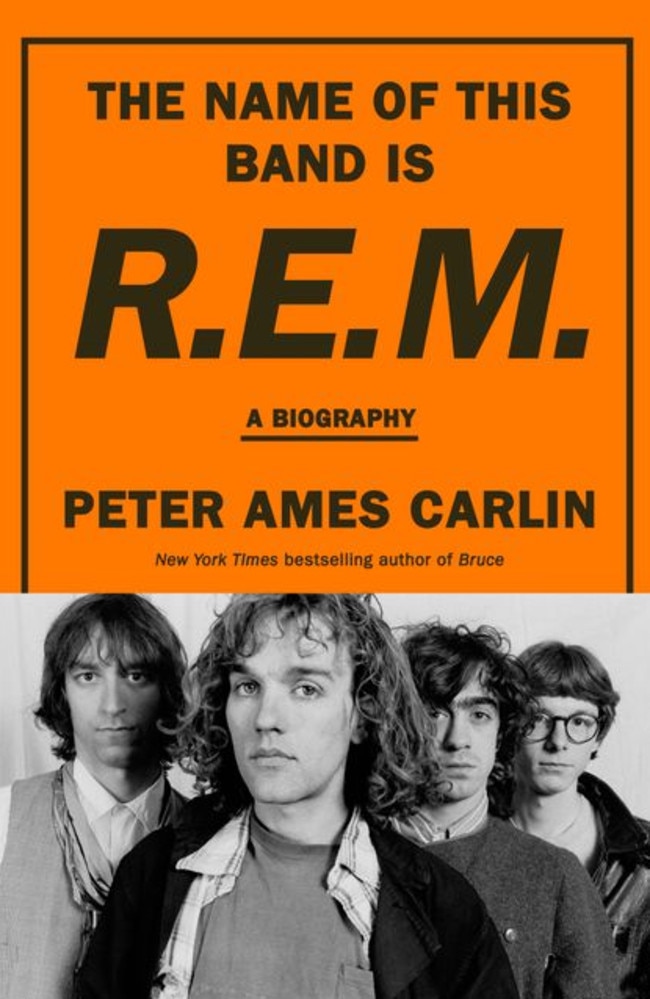

Rock biographer Peter Ames Carlin reveals the darkest hours of legendary ‘90s band R.E.M.

R.E.M. – one of the biggest bands of the 1990s – had just kicked off their biggest year before disaster struck. It changed their future.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

R.E.M. were one of the biggest bands of the 1990s – and their biggest year began with a tour in Australia and a wedding before disaster struck, as rock biographer PETER AMES CARLIN describes in The Name Of This Band Is R.E.M.

This was how R.E.M.’s biggest year began.

On January 5, 1995, at Los Angeles International Airport, which briefly took on a tinge of Beatlemania. The band of the moment caught in transit, fielding questions about their new concert tour, their first in half a dozen years. The musicians were charming, bemused if not surprised to find themselves the subject of so much fervent curiosity. Next stop was a private conference for MTV, which was airing it live around the world, underscoring how significant R.E.M. – whose new album Monster had followed the wildly successful Automatic For The People and Out Of Time – had become to the network and to the tens of millions of largely youthful viewers watching all across the globe.

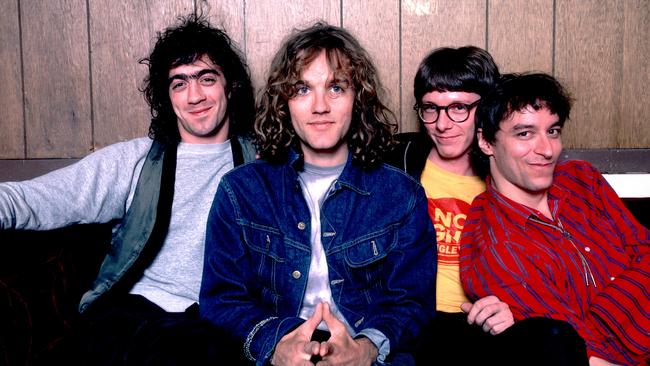

Bound for the tour’s opening concert, in Perth, Australia, the musicians were all dressed for comfort. Bass player Mike Mills in a white sweatshirt and jeans, drummer Bill Berry in a corduroy jacket, black jeans, and a T-shirt, with a tall, muffin-shaped hat and, less explicably, a spoon tucked behind his ear. Frontman Michael Stipe also wore jeans and a T-shirt, with a black watch cap pulled over his head and a scruffy blond goatee bristling on his chin. Guitarist Peter Buck was running late because his flight from Seattle had been delayed. Or maybe, as a prankish Bill announced, he’d just been fired.

“So all you young, aspiring guitarists, send your resumés in.”

More questions, more jokey answers, more glimpses behind the scenes of the moment’s biggest rock band. How did they keep themselves entertained during long flights? Mike said he planned to sleep and play games on his portable backgammon set. What was the weirdest thing they packed? Bill pointed to the utensil tucked behind his ear. He’d heard they don’t have spoons in Australia, he said.

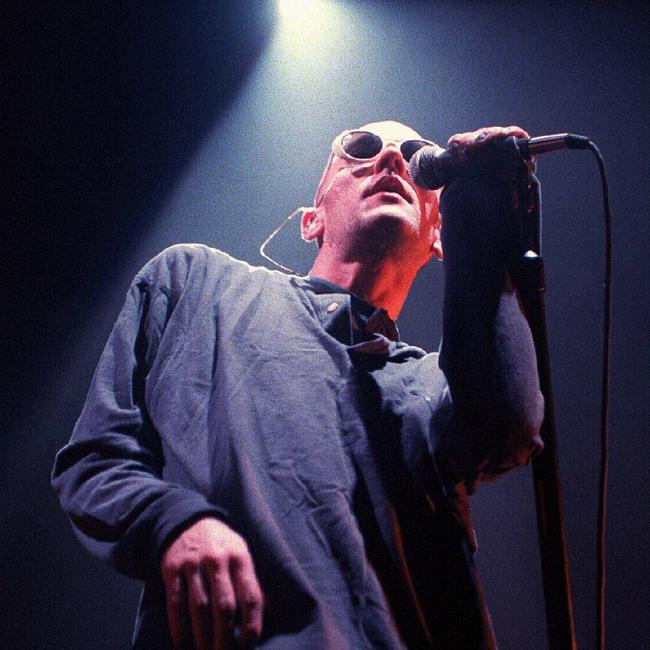

The Perth Entertainment Centre, January 13, 1995. The first moments of the first night of the world tour. When the arena lights flicked off, a vast roar filled the blackness. Eight thousand Australians standing up and going waaaaaaaahhhh! The moment lingered and expanded on itself. So much at hand, so much at stake.

Onstage, they could feel a solid wall of noise coming at them, the power humming in the amps. The musicians slipped into their places, instruments in hand, the electricity in their fingertips. This moment they’d first anticipated in the spring of 1993, that they’d hoped for and dreaded, that they’d dreamt of, that they’d argued about, that they’d been planning and preparing for, was right here, right now.

Peter, his left hand holding the neck of his guitar, took a breath, then raked a pick over the strings, sending a loud buzzing chord into the air. Then another chord, tripping a blast of drums and a bolt of clear light revealing the musicians and Michael, shouting a single word into his microphone.

WHAT!

The drums and bass hit and they shot off together into “What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?”

THE WEIGHT OF CELEBRITY

During the 1980s, touring had been R.E.M.’s way of being. They’d travelled all over the world, by car, van, bus, train, boat, and aeroplane, had performed in venues large, small, and midsize, had faced audiences that ignored them and audiences that sang along with every syllable. But they had never toured as international celebrities, and what soon became clear was that this made for what Peter called a “weirdly unpleasant” experience.

Previously, whenever they’d found crowds waiting outside a hotel, they’d assumed someone far more famous than they were was also staying there. This time around, the crowds were looking for them. “Your phones would be ringing at weird hours, people would camp in the hallways,” Peter told journalist Tony Fletcher. “It was so f**ked up and chaotic I quit drinking. I stopped drinking in February and didn’t have another drink until the end of November. I was just like, this is too insane. I have to be sober for this whole thing to keep it together.”

Peter also had his new wife Stephanie Dorgan and their twin baby girls to keep him grounded. They got married in Perth on January 12, with the touring party in attendance and music provided by tour openers Grant Lee Buffalo. When a reporter mused about how he’d sacrificed a honeymoon with his bride by getting married the day before the start of a world tour, Peter chuckled. “I get to play guitar and travel all over the world,” he said. “That sounds pretty much ideal to me.”

The band members did their best to keep their inner circle insulated from the weirdness triggered by their fame, and from the more toxic habits and rituals of the rock ’n’ roll road. They revised their standard performance contract to limit the backstage beverage options to soft drinks, beer, and wine, no more bottles of vodka, scotch, and gin, thanks very much, and to make sure the buffets had plenty of vegetables and other healthy options for band and crew alike. They brought a treadmill for Peter and Bill to exercise on, while Michael combined his exercise with sightseeing, pulling a hat down over his head so he could explore his whereabouts on foot without drawing attention. Bill and manager Bertis Downs brought their golf clubs, and if there was a course anywhere nearby, they’d take off together to get in nine holes before soundcheck.

After the shows, the band members and their wives or romantic partners often got together in the hotel bar or in someone’s room to unwind with party games – charades or a board game, Pictionary and Trivial Pursuit usually. “It wasn’t rock-star-like,” Bill’s ex-wife, Mari, recalls. “Not a lot of partying. It was family-like, very quiet. People got really obsessed with the games.”

ONSTAGE IN LAUSANNE

The explosion of light and sound, the cheers and applause coming at you like a wave, a physical thing strong enough to knock you off your feet. This was where Bill could hit his drums hard enough to keep the noise and chaos at bay, where his beat kept everything orderly, moving at his pace. After fifteen years together, and now nearly two months into the tour, the performances were built on a combination of physical energy, emotional projection, and muscle memory. Michael’s job was a little different, channelling so much feeling into the words he sang, his focus divided between singing, moving, and monitoring the crowd while also listening to the band. Behind him, Bill focused almost exclusively on the music, keeping his beat straight and strong, adding harmonies when his parts came up.

Then they were off, into the opening suite of Monster songs, then a pair from Out of Time, “Me in Honey,” “Half a World Away,” usually with one or two from Automatic. It was always great to hear the ovation the songs from the previous few albums got when they started playing them; nobody complained about not hearing “Radio Free Europe” or “So. Central Rain” or any of the early ones they’d put away. “Man on the Moon” was always a highlight: the music had such a nice groove, and Michael had taken to emphasising the whole Elvis aspect, he’d be all slinky hips and sexy Memphis drawl for the Heeeey bay-buh bit, and the crowd loved it every night. That was a real pleasure for everyone, and also the point in the show, on this late winter evening in Switzerland, when Bill felt something go wrong.

A piercing throb in his head. A lightning bolt of pain he could nearly see, and certainly felt, behind his eyes. He might have slowed down for a moment or two, his backing vocal might have dropped out, nobody remembers. Somehow he got to the end of the song.

“Man on the Moon” almost always prefaced “Country Feedback,” at which point Bill switched to bass, so back-up guitarist Nathan December was used to seeing the drummer heading his way just after “Man on the Moon” ended. Usually they’d have a moment or two to check in, trade a joke or laugh about something that had gone sideways earlier in the show.

But now something was different about Bill. He was pale, and faltering. Usually he’d sling the bass over his shoulder, but now he was swaying on his feet. “God, Natty, I don’t feel so good,” he said. His head was killing him, he needed to sit down for a second. Bill leaned on the bass amp, December recalls. Then he keeled over. “It was the scariest thing on the planet,” December says. “We had no idea what was wrong.”

Peter, seeing Bill go down, dropped his guitar and ran over, as did a roadie or two. Together they pulled Bill back to his feet. He was conscious, sort of standing, but then he fell into Peter’s arms. Peter and December helped him offstage.

They got him to the dressing room and laid him down on a sofa. Bill was conscious and talking. He’d had migraine headaches; those could take him down for a day or two. But this wasn’t that; this was pain like he’d never experienced before. A couple of EMTs came in, took his pulse, peered into his eyes, asked the first question you ask a rock musician who collapses onstage: Was he on something? No?

Well, better to not take him to the hospital — they’ll just assume he was overdosing. He had to get out of the hall, though; there was no way he was going back onstage. The EMTs put him on a stretcher and wheeled him away, taking him back to the hotel. But the crowd was still out there, stomping and cheering, waiting for R.E.M. Would they call it quits or …? No.

Someone ran to find Joey Peters, the drummer for support act Grant Lee Buffalo, who was unwinding in his band’s dressing room. Could he play Bill’s parts? Yes? He grabbed some sticks, sprinted to the stage, the house lights went off, the show went on. The band cut the rest of the set down to the essentials, came off the stage blank-faced and anxious, and were relieved to hear that Bill was resting in his room. It was a bad migraine, but he seemed fine.

Bill wasn’t fine. The pain radiated down to his shoulders. Mari massaged his neck, but then he was nauseated and threw up. He couldn’t sleep — it hurt too much. Mari wondered if he had meningitis. At 6am she called for an EMT, who came to the room, heard about the neck pain and nausea, put it all together, and called the hospital: Bill had suffered a brain bleed and needed immediate help.

They put him back on the gurney, got him down the stairs and back into the ambulance, now with lights and sirens, heading to the hospital, where some kind of fate awaited him.

This is an edited extract from The Name Of This Band Is R.E.M. by Peter Ames Carlin: available now, published by HarperCollins.

Originally published as Rock biographer Peter Ames Carlin reveals the darkest hours of legendary ‘90s band R.E.M.