From hate, fear and Psychobitch to ‘romance’ and the phone call that changed everything: How Cheng Lei survived inside

Australian TV journalist imprisoned overseas tells of deadly beatings, blindfolded inmates – and how a secret code spawned romance in “the ugliest, most hateful place”.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australian TV journalist CHENG LEI endured three years in the Chinese prison system, amid bogus claims of espionage, after breaking a media embargo by minutes. In this exclusive edited extract from her memoir the mother-of-two describes her terrifying first interrogation – and how she learned to survive inside.

First, the cell.

Blindfold removed, bracketed by two female guards, I surveyed the room: a bathroom with no door, a single bed and a dark brown stool. Nothing else.

A female doctor gave me a medical in the cell.

Next, I was taken to the interrogation room. I was put into a dark wooden restraint chair that faced a desk, behind which sat three officers in full uniform. The main interrogator introduced himself as Li. He was the man with the dark complexion who had come to my work to detain me. A video camera stood on a tripod and behind me were large LCD time displays. There were officers outside watching the feed and texting messages to the interrogators.

With Li was an older man who didn’t say much, just stared at me, and a young female officer transcribing. She radiated hate towards me in all things she said and did. I couldn’t work out how it was personal to her. Perhaps she had been spying on me? Headphones in a van listening to my raucous laughter? Did she hate ‘whores’ who slept with foreigners? Was she the offspring of diehard Communists and saw me as the ultimate enemy of the state?

Another thought popped into my head as to why I was being investigated. Maybe because Australia–China relations are not good? To say the least.

‘This is not hostage diplomacy.’ Li shook his head and pronounced the words officiously, emphatically, smirking a little. I thought of the old saying among China correspondents: ‘It’s not true until a Chinese official denies it.’

During my first two weeks in detention, I was interrogated almost daily. Each time, the ocean of fear deepened. I thought of others who had been in my place: the tycoon husband of an acquaintance, who was beaten to death after twelve hours in similar detention up north; the female half of a society power couple rumoured to have peed her pants when taken away for questioning by the Ministry of State Security; my former co-anchor and once darling of the TV station, who’d been put away for six years in northern China for supposed bribery.

SQUAT TOILET, RELEASE WIND

Lei endured months of mental and physical anguish in solitary, forced to sit motionless for up to 14 hours a day with two guards in her cell 24/7. Finally, she was moved.

I had been counting down the days. As a sociable extrovert, not talking for virtually six months had been like keeping Cristiano Ronaldo from the gym.

When the door to cell 112 opened, I took off my blindfold, stood up from the wheelchair – that was how they moved us around – and crossed the threshold into what would be my home.

The cell was three metres wide, seven and a half metres long and five metres high. Near the ceiling were windows that officers on an elevated walkway could look through. Taking up most of the space was a two-by-six-metre-long bed with six storage compartments underneath. The doorless, glass-walled bathroom had a squat toilet, a shower and a shin-level tap.

‘Hello, everyone!’ I said brightly.

Three women in grey uniforms, their faces pallid in the grey light, looked at me without expression. Their ages were staggered – I guessed around sixty, fifty and thirty-five.

The woman aged about fifty came over to help me with my things. The officer introduced us, using our numbers to identify us.

I was given sleeping position two, second from the door, and my things would go in the compartment under that part of the bed.

‘You women don’t know how good you have it. The conditions here are top notch. You really should behave,’ the officer said in a lecturing tone before he left.

It was ‘sitting’ time and I had no book, so the youngish woman lent me one. Soon a ding-dong sound announced a change of activities, like a shift change in a factory. We were going to ‘release wind’! (In Chinese, going out for air translates literally into ‘release wind’.)

My cellmates amusedly watched me as I rushed to the other door, images in my head of prison exercise yards on TV and in movies with plenty of space and grass and Red from The Shawshank Redemption waiting to sell me cigarettes. What greeted me was a three-by-three concrete enclosure with a glass walkway above and two small windows at the top of one wall – that was the extent of the sky you could see.

‘This is the exercise yard?’

‘Yeah, I thought so too when I came!’ the others chorused.

CELLMATES AND PSYCHOBITCH

Lei got to know her cellmates, giving them nicknames, as she faced an existence of food shortages, health challenges and little contact with the outside world.

The top sources of friction in a cell were: bathroom usage, chores, cleanliness, adherence to rules and snoring. Like anywhere, if you followed social norms of considerateness, you generally wouldn’t have trouble. As I did everything fast, I didn’t think I would get on anyone’s nerves.

But Prisoner 02 wasn’t just anyone. One day, when she was taken out for interrogation, OG and Canto unloaded with great relish. Much had gone down in the cell before I arrived. 02 was a very difficult cellmate, and even the officers said she was crazy. She lied often, sometimes blatantly. A month earlier, Canto and 02 had got into a fight and were punished. It was over something as trivial as who had splashed a few drops of water on whose vest.

This living with cellmates business proved to be trickier than I’d thought, although I was determined not to get involved. Sometimes it felt like my cellmates were one word away

from erupting into outright hostilities.

In time, I would give 02 the nickname PsychoBitch; I would spend three awful months in a cell with her alone and discover she was being held on espionage charges; later still, OG would become the problem.

CHRISTMAS IS CANCELLED

Christmas 2021 was my first in the detention centre.

Our plan was to learn ‘Silent Night’ and ‘Jingle Bells’, and sing them on Christmas Day in the exercise enclosure. It would make us feel like we were having a little Christmas, taking us to snowy Christmas fairs in Europe, to grand churches glowing in candlelight. If other inmates heard it, even better. For days Canto, Skinny and I rehearsed, much to the annoyance of OG. While she didn’t want to join in, she hated that we had something together.

‘Merry Christmas!’ I said to everyone cheerily on Christmas morning. As soon as the exercise bell rang, I skipped into the enclosure and waited for my ‘choir members’ to join me.

‘We’ll sing “Jingle Bells” first. You remember the words?’

I clapped and stomped my feet as we belted out the most overplayed Christmas song of all, the catchy melody that drove shoppers around the bend. We hadn’t got halfway through when the buzzer inside sounded. ‘Stop singing! So loud! It can even be heard outside!’ Officer Zhang said.

Yes, that’s the point.

‘I bet PsychoBitch reported us,’ Canto said.

We shut up, but the singing continued inside us.

I hadn’t heard any music for more than a year, except for the daily wake-up and go-to-sleep piano music. I used to have music on from morning till night – and in the detention centre, I tiptoed back into its wonderland. Once we started singing, something woke up. I taught my cellmates sixty songs: ballads and rock classics, from the Beatles to Roxette, from ‘Hallelujah’ to ‘Brown Eyed Girl’. ‘Amazing Grace’ was our go-to comfort song. Even those who knew no English would be brought to tears by the hymn and ask to learn it.

Singing would become one of our most treasured, controversial and troublesome activities.

INTO THE TALKING ROOM

I had been waiting for this day for two years; the Australian government had asked for this day for two years. On 3 December 2022, I would get a thirty-minute phone call with my mum and kids.

After my Saturday morning shower, I was taken upstairs to the ‘talking room’. The mean-spirited officer we’d nicknamed Eunuch walked me through the details of the call, then put on his scary face and said that I would only get the call if I satisfied three criteria.

1. Do not say anything about the detention centre.

2. Do not cry. You have it easy here, we treat you well, so don’t

make out like it’s a hardship.

3. Do not tell anyone in your cell about the call.

A judge and various officers were present. There were technical difficulties, but they kept trying. Then, miraculously, from 9113 kilometres away, data packets that had started at the Chinese consulate in Melbourne zipped through cables, routers and switches, between international and local networks and reassembled before entering the phone I was holding in Beijing.

‘Mama!’

‘Baober! (Baby!)’ The primal call and answer.

I’ll never forget the thrill of hearing Alex’s voice again. It was unmistakeable – the 99 per cent breathless boyish rasp, 1 per cent high-pitched shrill voice has a pull on my heart, a hold on my being. The officers all around me, the darned restraint chair, the dull wintry day were all wiped out by the landslide of emotion.

Ava’s voice caught as soon as she called ‘Mama!’ I remembered the warning from Eunuch, and led her away from tears into the high-octane teen speak of her letters.

Mum called me by my childhood name, Leilei. How I had missed her calling me that! She was holding back her emotions, I could tell, because she spoke in a deliberately soft voice.

We babbled and giggled, even breaking into the Justin Timberlake song ‘Can’t Stop This Feeling!’, which we used to always sing together and dance to.

For the first time in god knows how long, I was neither a number nor a criminal – I was a person, a mother. On some plane, I was reunited with my dearest dears and had received their verbal embrace, which filled me, moored me, the missing pieces slotting into me.

‘I CRIED FROM THE ROMANCE’

Defying the rules, Lei and her cellmates began communicating with neighbouring male prisoners via a secret knocking code – even learning one was a colleague from her TV network – until they were discovered.

It was weeks since we had been caught ‘talking’ to the other cells.

Sometimes we heard a few phantom knocks, or attempts to ‘type’ out a message, but the fear of being found out was too great. We didn’t reply.

Considering what we had done – break the rule against intercell communication – I only got a rap over the knuckles, although they moved our lead knocking-mate, Prisoner 20012, somewhere else, which to me was the harshest punishment.

So when we heard the familiar knocks in his decisive style, Canto and I looked at each other with mouths agape.

Should we risk knocking back? We decided to go for it. Then we heard his voice, loud and clear through the top window. ‘I got you a book. I Am a Cat. It’s in your locker. There’s a poem in there!’

I felt the ground shake as the enormity of his daring hit.

It wasn’t the first time he’d pulled this off. Once before he’d wiped off his number from the sticker on a book and written mine on it, then told the guards, ‘This book was mistakenly put into my locker.’ When I saw it, I was amazed and moved beyond words and we were all impressed by his chutzpah.

But now the atmosphere in the cell had changed. It felt like a ticking bomb.

I knew that OG was in hate mode, even though we observed the usual courtesies. When the guard gave me the well-thumbed book, I felt a tightening in my stomach.

The corner looked tattered and, upon closer inspection, I could see the cover had been sliced open and glued back again meticulously. Inside lay a thin piece of paper about a square inch in size. On it was a poem written in traditional Chinese style with both my name and 20012’s name cleverly hidden in it.

The poem sent me reeling. But there was more. Dozens of coded messages on pages with meaningful numbers, like 203 and 23 – 2 sounds like ‘love’ in Chinese and 03 was my number. He had used Tang to colour certain characters and spell out messages.

He had also highlighted a line in the book: ‘Will you marry me?’

Oh god oh god oh god. I felt a thousand things all at once.

So young and so doomed. I knew things did not bode well for him. Was he trying to give himself hope? Or offer hope to me?

Had I led him on? Didn’t his cellmate tell him about me – the Aussie partner, two kids?

I cried from the romance of it all – beauty and love in the ugliest, most hateful place.

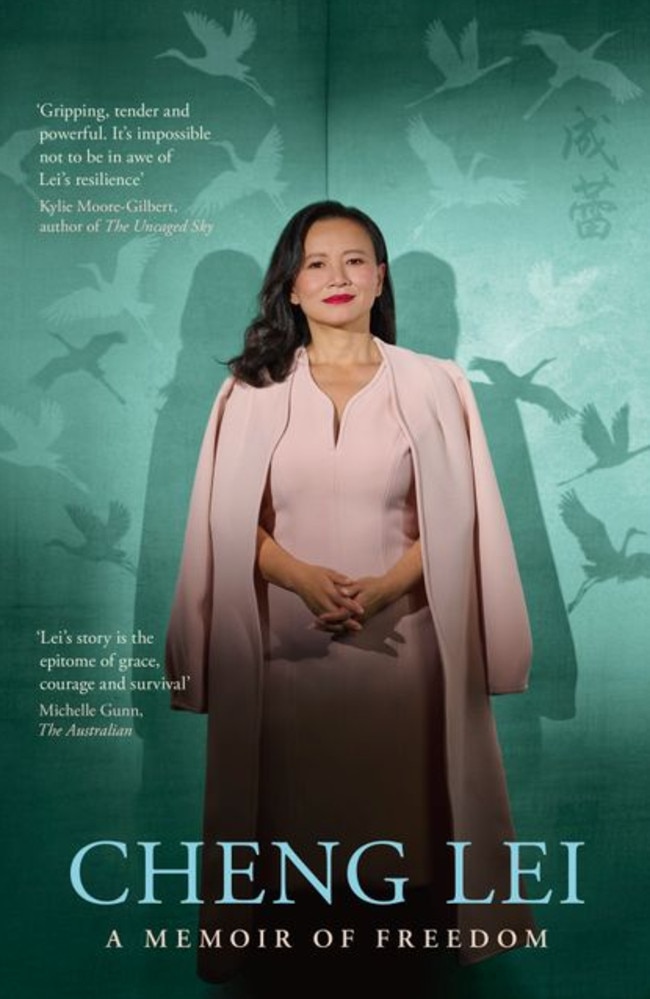

Cheng Lei: A Memoir Of Freedom by Cheng Lei will be published by HarperCollins on Wednesday, June 4 and is available to pre-order now.

Cheng Lei: My Story will premiere on Sky News Australia at 7:30pm on Tuesday, June 3. Stream at SkyNews.com.au or download the Sky News Australia app.

More Coverage

Originally published as From hate, fear and Psychobitch to ‘romance’ and the phone call that changed everything: How Cheng Lei survived inside