Did she really do it? How Jean Lee confessed to murder then changed her story before execution

Jean Lee and her lover gambled that a woman would not be executed for a crime that would see a man hanged – and one ex-con still recalls the dark shadow of their fatal decision.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

To this day, her ghost is said to haunt the brutal place she died, declaring “I still love you, Bobby”.

According to a former guard at Pentridge Prison – one of many staff, criminals and historians quoted in a new book on the notorious institution for Australia’s worst killers and gangsters – Jean Lee has never truly left the terrifying Melbourne penitentiary.

She was hanged there, aged 31, on the basis of a “confession” that raised as many questions as it delivered answers, refusing opportunities to save herself until it was too late.

In this exclusive extract from Australia’s Most Infamous Jail: Inside the walls of Pentridge Prison, author JAMES PHELPS re-examines the fascinating and tragic story of the last woman judicially executed in this country.

“And they call women the weaker sex.”

Former Pentridge inmate Jean Lee

1949. The detective stubbed out his cigarette in the full-to-the-brim ashtray. This had gone on for long enough. Dishevelled, tired and out of patience, he stood up, straightened himself and stared, hard, across the table.

‘You did him in,’ he shouted. ‘You killed this poor old man.’

The woman sitting opposite leaned back and folded her arms. ‘I’m not saying anything,’ she said. ‘I’m not answering any questions.’

Jean Lee looked as though a stiff breeze would knock her over. She was the girl-next-door type. Thirty according to her papers, but she looked younger. Even now, at 5am, bags under her bloodshot eyes, she could have passed for 25.

The detective grunted before leaving the interview room.

Senior Detective Cyril ‘Smugs’ Currer had gotten her wrong. He thought he’d have a signed confession before he’d even finished his first smoke. But here he was, twenty cigarettes down, and losing his cool.

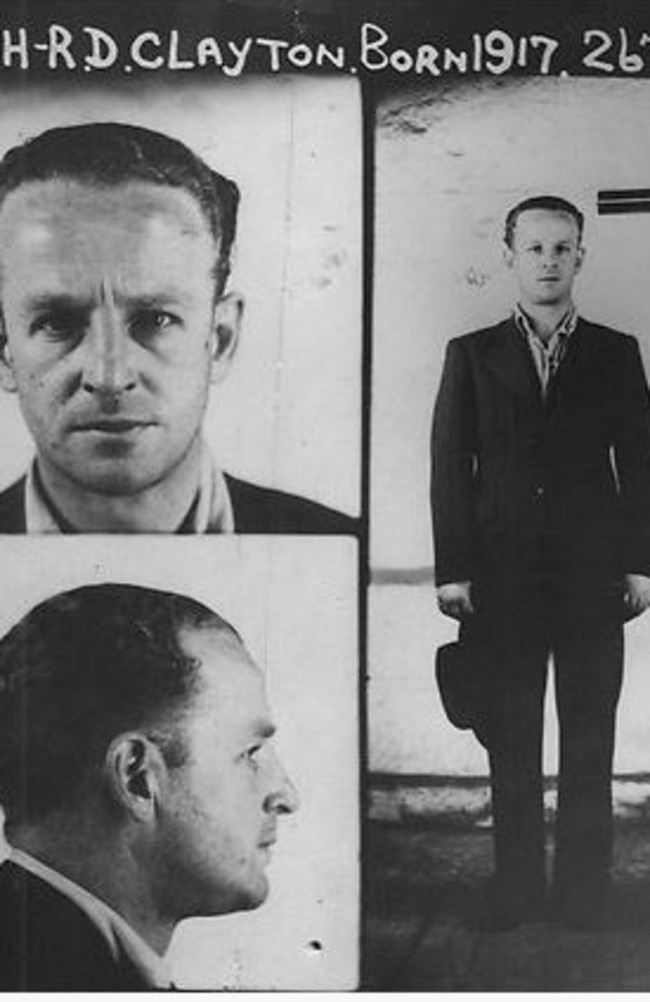

Currer stopped in front of the second interview room and looked through the window. Robert Clayton was all fidget and fuss. Sitting by himself in a cool concrete room, his fingers tapping away on the table, teeth grinding, skin covered in sweat. He looked like a man who had just finished a marathon.

Currer wanted to kick himself. Weak link. Yeah right. He’d thought Lee would be easy because she was a woman. Lesson learned.

Currer went back to Interview Room No1.

A few minutes later his fellow detective, a serious man named Ray Mooney, came bursting through the door.

‘He’s put you in,’ he beamed as he looked towards Jean Lee.

‘That so-called husband of yours said you did it. He said that you and Andrews did him in.’

Currer looked Lee straight in the face. Breaking point. She squirmed in her seat.

‘Well,’ Currer said. ‘What do you have to say now?’

•••

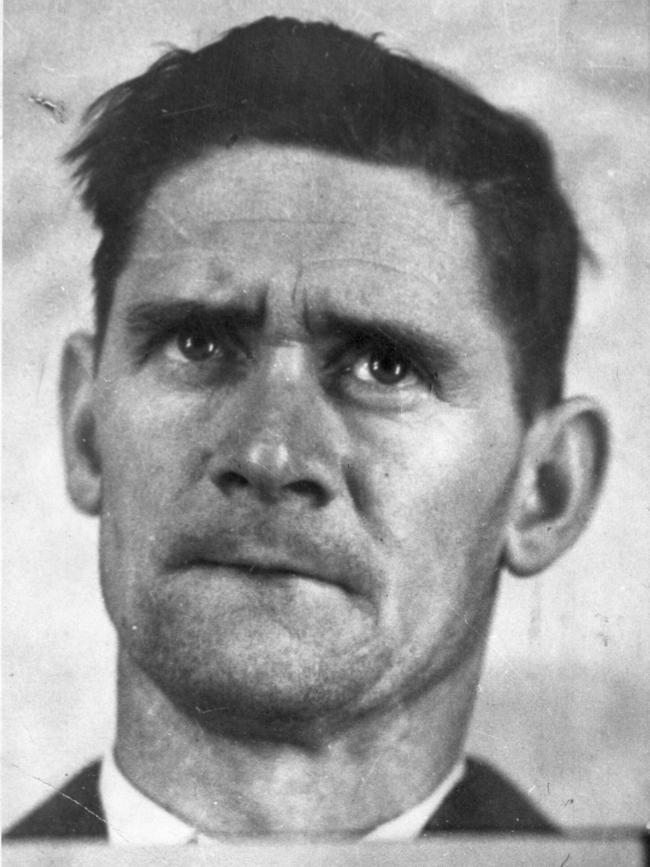

Currer did not think that Lee had killed Pop Kent, the 73-year-old SP bookmaker who had been beaten, stabbed and finally strangled to death in his Carlton apartment the night before.

She had been at the scene. Absolutely. Witnesses had seen her chatting up old Pop at the Great Southern Hotel. She even bought the old fella the first beer, which the barman thought was weird because Pop was waving about a wad of cash. He was not exactly hard up.

Witnesses had seen her leave the bar with Pop. Singing, dancing, swaying, and saying they were going to Pop’s house to drink some more. Witnesses saw her go into Pop’s house at about 6.15pm. They also saw her leave at 9pm.

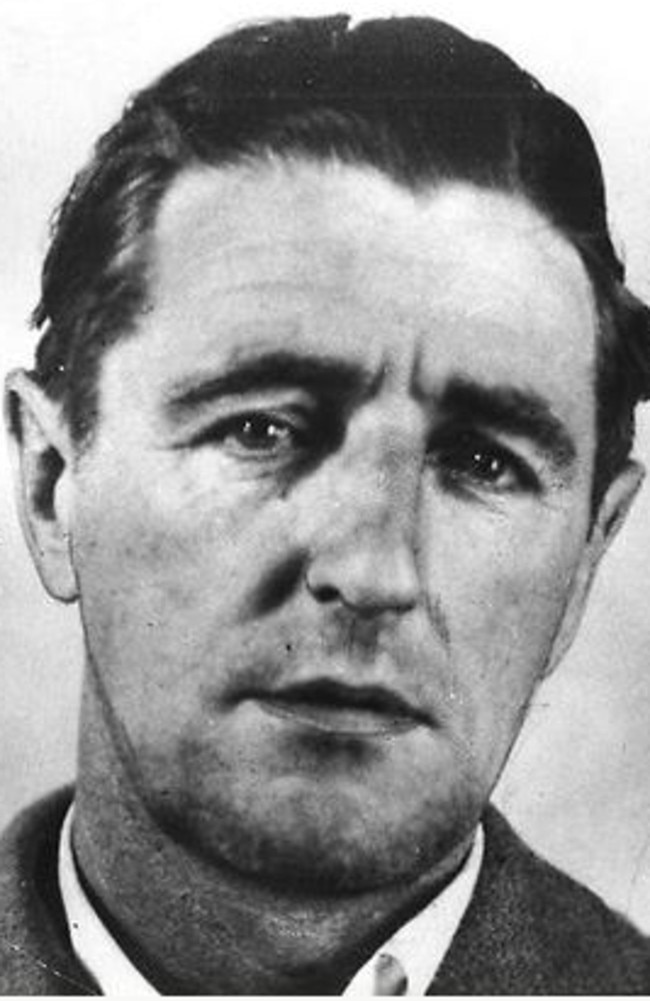

But it wasn’t Lee who Currer had fingered for this one. She had been an accessory, maybe even accomplice, but he figured it had been one of the two men with her who had done all the beating, stabbing and strangling. He didn’t know if it was her lover, Robert ‘Bobby’ Clayton, who she said was her husband, or Bobby’s friend, Norman Andrews. They both looked the type. Both had form. Both were in Pop’s apartment between the hours of 6.15pm and 9pm on the night of 17 November 1949.

Lee would have played her part. Bobby and Norman wouldn’t have gotten into the apartment without her. A prostitute and a player in a robbery gone wrong? Yes. But a murderess? No, the coroner had already said the cause of death had been strangulation by hand and that only

a man would have had the strength.

‘So who did it?’ Currer pressed. ‘Was it Andrews or was it your Bobby? What do you have to say?’

‘Nothing,’ she snorted. ‘I won’t say a thing against him. Against either of them.’

Currer hadn’t expected this. Staying staunch and refusing to save herself? No way.

Currer answered: “Do you really think he won’t put you in? Think about it. When was the last time a woman swung? I’ll tell you … A good fifty years ago. And that’s what your Bobby is thinking. He’s done the maths. He knows he will hang if he cops to this and he

knows you won’t. He will justify all this in his head by thinking they’ll go easy on you. But mark my words, you will hang for this if you don’t speak up now.’

Lee just shook her head.

Currer was going for his last Camel when Mooney came back in.

‘He has really put you in,’ Mooney said. ‘He’s put it all in writing. Made a statement and signed it.’

Lee shook her head.

‘I don’t believe it,’ she said. ‘I want to see it before I believe it.’

And Currer did not believe it either. Not until Mooney walked in holding the document. He slammed the statement on the table. The statement was signed by Robert Clayton. The ink was black, fresh and heartbreaking.

‘This is a lie,’ Lee screamed as she pushed the statement away.

‘Do you want to hear it from him?’ Mooney left then returned with Clayton.

‘Did you make this statement?’ Lee snarled.

Clayton went to speak, but he couldn’t get anything out.

Mooney gave him a shove.

‘Yes,’ Clayton blurted. He went to say something else and instead started to sob.

Lee stared daggers at her lover.

‘And they call women the weaker sex,’ she scoffed.

Clayton tried to speak again.

‘I’m, I’m, I’m sorr—’

Mooney dragged him away.

‘Bobby,’ Lee screamed. ‘I still love you. But if that’s the way you want it, then you can have it.’

How could he? She must have been thinking. He couldn’t have.

Right? But he had. Fine. If that’s what he wants.

‘I did it,’ Lee barked, looking Currer square in the eye. ‘Pick up your pen and take this down. I did it all. Everything that he said is true. It’s all on me.’

Currer did not know what to say.

‘It’s all true?’

That was the best he could do. The statement was dripping with disbelief.

‘No, not all of it, I suppose,’ Lee answered. ‘It’s all true up until the part where he said he left the room on his own. Norman left with him. I did all this on my own.’

‘You’re kidding, right?’ Currer said. ‘Alone?’

‘I sort of done my block,’ Lee said. ‘I hit him with a bottle and a piece of wood. I cut my finger.’

‘What happened to the old man?’ Currer asked.

‘He fell over on the chair and then fell on the floor,’ Lee replied. ‘Then I tied up his arms with a piece of sheet and then left the place.’

‘Did you tie his hands?’ Mooney asked, who had re-entered the room.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘That’s right. I tied his arms with a piece of cord.’

Sheet or cord? Currer should have pulled her up. But his jaw was still on the floor.

‘Did you rob him?’

‘No. But I knew he was dead when we left him.’

‘ “We”? What do you mean by “we”?’ Currer did not miss that one.

‘There was only me.’

‘No, you said “we”,’ Currer said, back on his game and good to go.

But Lee did not want to play.

‘That’s it. I did it and that is all I’m saying.’

And she stuck to her word.

•••

The jury needed less than three hours to reach a unanimous verdict.

All three, guilty as charged. Murder in the first degree.

‘I didn’t do it!’ Lee cried out when the judge asked her if she had anything to say. ‘I didn’t do it!’

She collapsed into her Bobby’s – Clayton’s – arms.

‘And how about you, Mr Clayton,’ the judge said. ‘Do you have anything to say?’

‘All I can say would fill a book!’ Clayton screamed. He looked towards the jury. ‘You are a bunch of idiots.’

Andrews declined to comment.

‘Prisoners at the bar,’ the judge said, ‘the jury has found each of you guilty of murder and I need only say that it was on the strength of evidence and that I thoroughly agree with the verdict.’

The judge turned and gave the court orderly a nod. The orderly placed a folded square of black silk in the judge’s wig.

Then the judge delivered three sentences: death by hanging.

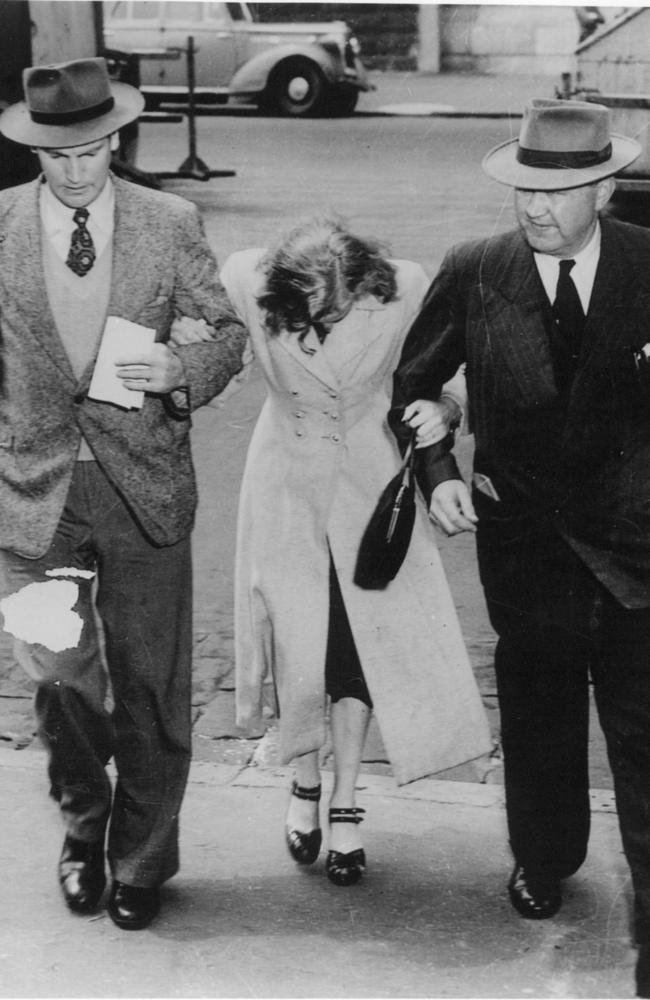

Clayton left the courtroom kicking and screaming. Andrews went without saying a word. Lee was carried out.

The trio was given a reprieve when the Victorian Full Court quashed all three convictions after ruling their statements were taken under duress and that the police did not adhere to

procedure. The sentences, however, were reinstated a month later when the High Court of Australia ruled that the statements were obtained legally.

•••

Jean Lee, born Marjorie Jean Maude Wright, was dragged, kicking, screaming and clawing, to the condemned cell in D Division the night before her execution. She was the first woman to be locked in the wing since it became an all-male wing in 1924.

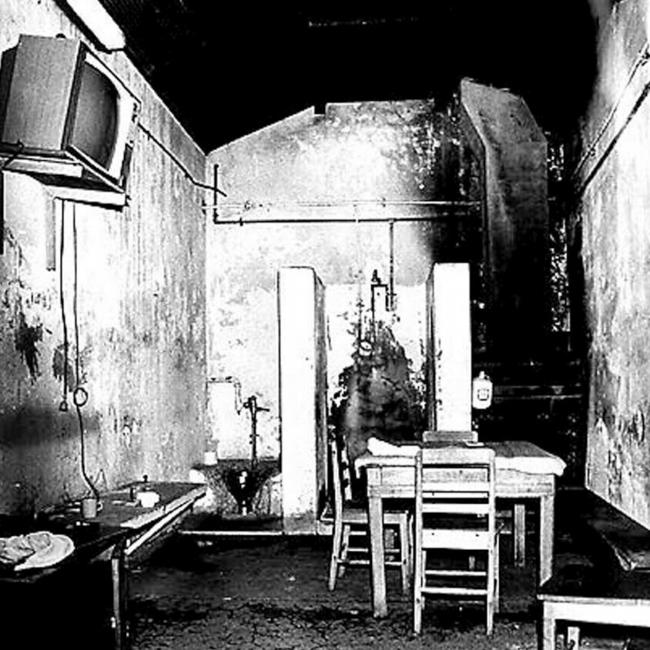

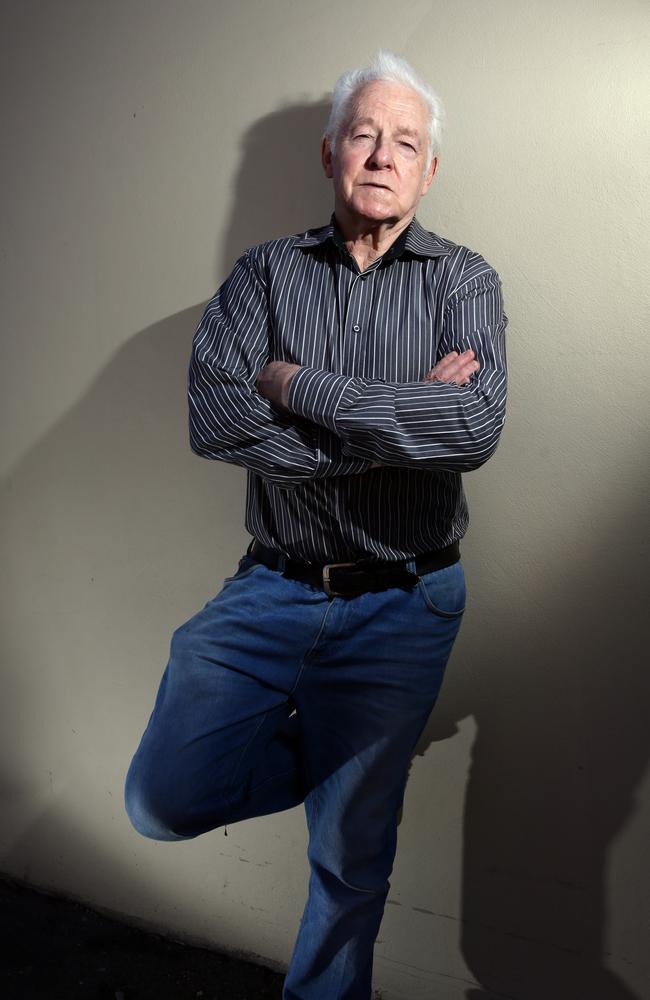

‘D Division was a horrible place,’ says John Killick, an infamous bank robber who spent time there in 1966 and who saw the gallows. In fact he was in the jail for the execution of the last prisoner to hang, in 1967.

‘It was really morbid to have them there,’ Killick says. ‘The stuff of nightmares. Everyone knew the stories of the people who had been hung in the wing. And it was a constant reminder of death. It was terrifying for the young fellas. You’d think about what had happened there. About all the people that were dropped from the rafter. The execution of ’51 was still fresh when I got there. You know? When they hanged all three of them at once? It was a really horrific one. They had to put the woman in the chair. What was her name?’

It was Jean Lee, of course.

***

Jean Lee was a wreck when her time finally came. Denied bail following her arrest, she had spent the last 13 months locked away at Pentridge.

Lee lived with hope for the first six months or so. Times were a-changing. While the right wingers in the print media, supported the punishment, a group of liberals campaigned to have Lee spared.

She had a stream of visitors in the beginning. Mostly women, they made promises and signed petitions. Lee, who denied confessing to the crime during the trial, continued to claim she was innocent and remained hopeful even after the petitions failed.

But that hope faded as the day got closer. About three months before she was due to hang she began lashing out at warders. She became so unpredictable that she was soon separated from the other inmates. A special list of rules had to be drawn up specifically for Lee, Pentridge’s first condemned woman.

Lee’s violence worsened as the countdown to her execution continued. She went on a hunger strike and threw her food and utensils at her jailers.

Lee was not told of Clayton’s confession. That he’d written and signed a statement on the eve of the executions, claiming he and he alone killed William ‘Pops’ Kent. He said Lee took no part in the killing and begged for her execution to be commuted.

Lee was instead dragged, kicking and screaming, to D Division and put in a condemned cell. She was then injected with a ‘sedative’ to ‘help her sleep’. She had no idea that her lover Clayton was in the next cell, or that Andrews was in the cell after that – in an unprecedented event, all due to be executed on the same day.

***

19 February 1951. Grey. Showers. Cold.

A crowd of protesters stood outside the main gate, holding signs in one hand and umbrellas in the other. A bell was rung at 7.55am. The executioner and his assistant were called into Lee’s cell.

They emerged a short time later, one on either side of Lee, who barely looked conscious. Her eyes were open but vacant. Her arms were dangling by her side. Wearing a pale yellow skirt and a white blouse, Lee had to be carried to the gallows – which wasn’t difficult given that she had withered away to a rake in the 469 days since her arrest. The hangman measured her weight and height to calculate the drop: 47.3kg, 169cm and 245cm respectively.

An exchange took place between the executioner and the sheriff when it became apparent that Lee could not stand on her own. The show had to go on. The executioner and his assistant held Lee as upright as they could.

‘Jean Lee,’ said the sheriff. ‘Do you have any last words?’

Lee did not respond. She didn’t even lift her head.

The witnesses began to murmur when they saw the chair they intended to sit Lee in.

‘What have they done to her?’ one asked. ‘She looks like she’s already dead.’

The executioner got on with it. He took Lee to the seat and strapped her down with a leather belt. He then tied her hands.

Next came the hood and, finally, the rope.

Lee was pronounced dead at 8.05am. She was left to hang, chair and all, until 9am.

Clayton and Andrews walked out together at 10am. They stood back to back, ropes around their necks, as Mr Jones walked towards the lever.

‘Goodbye, Robert,’ Andrews said.

‘Goodbye, Charlie,’ Clayton said.

They were dropped together.

The execution of the two men barely made the news. Lee, however, was plastered all over the front page.

She would go down in history as the last woman to be judicially executed in Australia. She was also the only woman in Australia to be executed in the 20th century. The last man to have a death sentence carried out in Australia would be hung in Pentridge too. His name was Ronald Ryan.

This is an edited extract from Australia’s Most Infamous Jail: Inside the walls of Pentridge Prison by James Phelps. It will be published by HarperCollins on October 4 and is available to pre-order now.

Originally published as Did she really do it? How Jean Lee confessed to murder then changed her story before execution