The Great Burnout: Exhausted Aussie workers forced into ‘quiet quitting’ and resignations

Aussies have revealed their “soul destroying” experiences at work and why they’re being forced to “quiet quit” as a new trend called The Great Burnout takes hold.

At Work

Don't miss out on the headlines from At Work. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One morning James woke up and was so “physically sick and mentally exhausted” he never returned to his job – needing months in bed to recover from “relentless” days that pushed him into utter burnout.

“It was probably the most soul-destroying work that I have ever had,” he told news.com.au.

“From February 2021 to August 2021, I was incapable of getting out of bed for three or four months – I didn’t do anything but see my medical team.”

The 44-year-old had joined an alarming number of Australians who are part of a club they never wanted to be in – which has been coined The Great Burnout.

A study conducted by The Future of Work Lab at the University of Melbourne revealed some alarming results about The Great Burnout experienced by Australians – primarily aged between 25 and 55 – due to the pandemic.

It found that a whopping 50 per cent of workers in those age groups were exhausted in their job, with about 40 per cent reporting feeling less motivated about their work than pre-pandemic.

The study also showed that 33 per cent found it more difficult to concentrate at work because of responsibilities outside of their job, while many saw fewer opportunities for promotions than older workers and did not have enough time to get everything done in their role.

“It’s perhaps no surprise 33 per cent of this prime-aged workforce is thinking about quitting,” Professor Leah Ruppanner, founding director of The Future of Work Lab, wrote in The Conversation.

“These workers may be showing up to their jobs but they are definitely burnt out. They are the ‘quiet quitters’ and they are sounding the alarm bell.”

Have a similar story? Continue the conversation | sarah.sharples@news.com.au

For James, who did not want his surname used, he started a new role as a sales director at a global business at the very worst time – just as Australia went into lockdown in 2020 – and he had moved from Byron Bay to Sydney for the job.

He wasn’t even sure if he would still have a job as the “world went into meltdown” but he was told by his boss to log on remotely where he would be introduced in a virtual meeting.

Initially from being forgotten as he was the “new boy”, not being given access to shared documents, folders or systems to understand what was going on and “blind” to what was expected of him, James spent six weeks wondering what he should be doing.

He invited himself to every meeting he could see, but then things got even worse.

“I went from desperately trying to fill eight hours a day to it ending up being a mess with a diary full of back-to-back Zooms for 14 hours a day with members of the team in LA, Sydney, South Africa, Melbourne, Shanghai and Hong Kong as there was less awareness of which time zone you are working from when you are virtual,” he said.

“If they could cram it into my diary, they did. The short version is, by July I was meeting with a psychologist going, ‘I am really struggling as I don’t know how to push back. I am nervous that if I push back I am still in my probation period and don’t have human connection in a virtual world so it’s easier to give me the flick.’ I was conscious of over-exceeding on expectations due to a lack of visibility.”

The back-to-back meetings meant James barely had time to go to the toilet or make himself a cup of tea. He said he also missed the human interaction, including mundane conversations about lunch in the office, as the pattern was to get into the meeting, talk work and then log off.

This carried on for seven months before James woke up in February 2021 and decided he couldn’t do it anymore.

“That human stuff wasn’t there. That is what literally drove me mad – and not mad in the angry sense but mad in the insane sense. I would just finish the day exhausted, self-medicate with alcohol and did the same thing all over again the next day with no physical social life as we were all locked up in Sydney,” he said.

“I know I am not the only one who experienced something akin to that in 2020-2021 but I had never been that low in my whole life.”

In October 2021, he decided never to return to the job.

“I just couldn’t imagine going back to work having that had amount of time off to recover from the ordeal and then having to re-establish myself as a leader in the business,” he said.

“It was not something that made sense or didn’t seem like a good use of energy.”

Women impacted by increased pressure

But it’s women in particular that make up a large number of those experiencing The Great Burnout, according to Prof Ruppanner.

She said increased childcare and housework during the pandemic on top of the pressures of remaining productive at work had resulted in poorer mental health, worse sleep and more anxiety for females.

“Women are increasingly concentrated in industries such as nursing, childcare workers and primary school teachers, all of which were particularly impacted by the pandemic. Young prime-aged women were particularly impacted during the early period of the pandemic and lockdowns,” she wrote.

“The pandemic was unforeseen, severe and detrimental to our working lives. Many Australia workplaces and workers continue to be impacted as the pandemic continues.

“Higher numbers of workers are taking sick leave, which may in part be driven by exhaustion and other Covid-related reasons.”

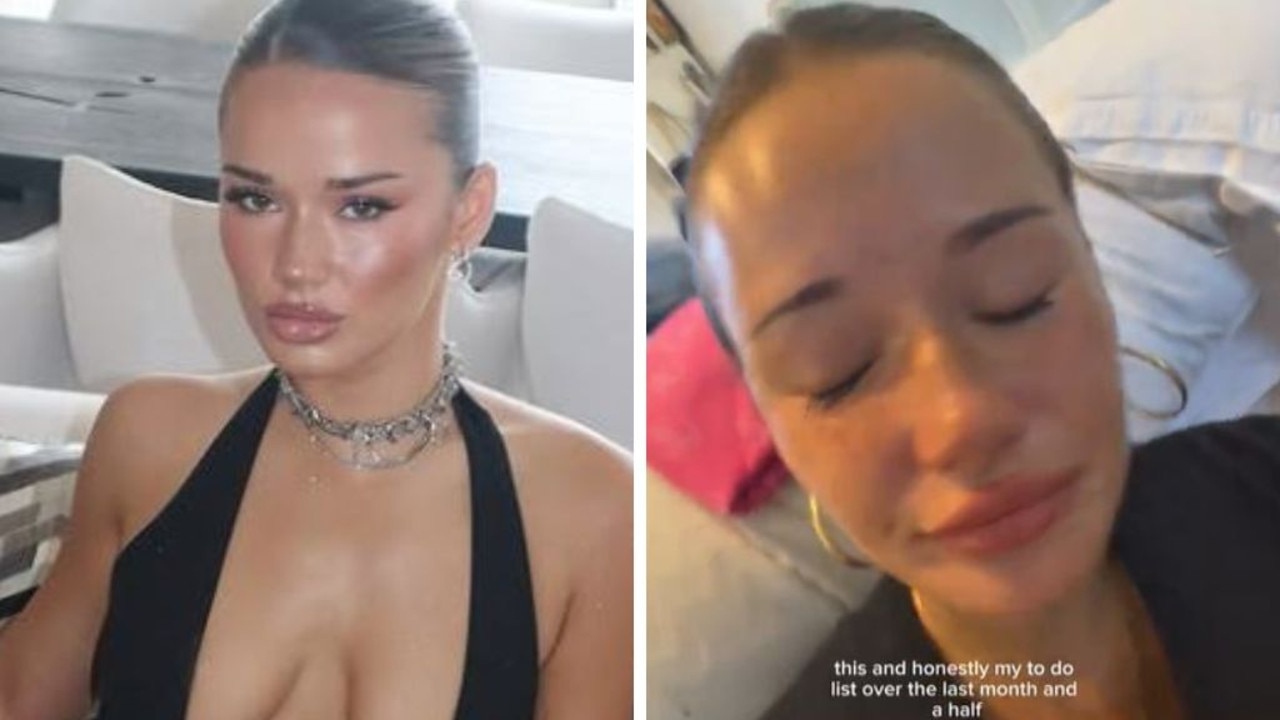

Nural Seker is one of those workers who were impacted. The high school teacher was so burnt out from the pandemic that she was forced to take long service leave to recover.

The Melbourne mum said she was teaching, helping students she had never heard from before as “they crumbled a bit with lockdowns”, offering support to families who were “struggling”, alongside leading a team of teachers.

On top of that, she was pretty much responsible for homeschooling her two children as her husband was out working. All of it combined to make her pandemic experience “just exhausting”.

“To the point where I went to the principal at the end of 2021 and I said, ‘I’m done – I’m going to take six months’ long service leave.’ And I tried to get another six months of unpaid leave at the start of 2022 but because of the shortage of maths teachers – we are hard to come by – I went back to work,” she said.

“But I’m still feeling the pressures of the burnout and exhaustion – I’m not co-ordinating, anymore and I’ve stepped down from further responsibility and I’m just in a classroom and it’s just as tiring.

“Nothing has changed and nothing is getting better and I can guarantee teachers everywhere are feeling exhausted like nurses and anyone who has worked through the pandemic.”

The 43-year-old said The Great Burnout is going to have dire consequences for the teaching sector.

“I think there are going to be even more shortages coming,” she said.

“It’s not going to be fixed really quickly and its due to exhaustion and burnout. Many colleagues and teacher friends are quite often saying, ‘I can’t keep working like this.’

“I think a lot of teachers are at breaking point and … unless something changes there will be many who will walk away, more so in the next couple of years.”

Ms Seker said she used the break to write a book called The Broken World Of Education and also launch her own business Learn What Can’t be Taught, which helps graduates just entering teaching.

Unfortunately, Ms Seker doesn’t have the option for one solution to tackling The Great Burnout.

Flexibility is the key

The study showed remote working could be key to stamping out The Great Burnout with 40 per cent of all flexible workers reporting feeling more productive since the start of the pandemic, compared to around 30 per cent who did not have the option.

In a warning to employers, 75 per cent of workers under the age of 54 also said that a lack of flexible work options in their workplace would motivate them to leave or look for another job.

For workers like James, flexibility has been key to his recovery and he is lucky that despite his experience there has been a happy ending.

Last month, he put his stuff in storage and gave up his apartment in Sydney to become a digital nomad.

Currently, he is based in Indonesia – but has big travel plans for the year – and has also started his own company.

“I’ve been moving around to different parts of Bali for two months, then I will go to Portugal, cycle from Portugal to Barcelona and go to Italy, Japan and over to Thailand and I can’t see it impacting work negatively,” he said.

“I think it can be quite the opposite and I see growing a global client base while moving around.”

He has also co-founded a business where he has taken a very different approach to the way people are asked to work.

“As an organisation we don’t have an office, we don’t have standard hours of work or any targets. People can work wherever they want, wherever they want, as much as they want and we are working to create a business with no expectations of its employees and we are thriving as a result,” he said.

“I’ve used the experience of either rigid expectations of what you can and can’t do, or hidden expectations of what you should and shouldn’t be doing, and [we] are trying to be really transparent.

“We have no expectations, we just want people who are committed to our mission and if you think you can add value and we like you then you can come on board.”

Originally published as The Great Burnout: Exhausted Aussie workers forced into ‘quiet quitting’ and resignations