The Azek takeover deal James Hardie shareholders can’t help but hate

After the asbestos scandal, building materials giant James Hardie is in hot water again, this time with shareholders who have been frozen out of a controversial takeover of US rival Azek.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

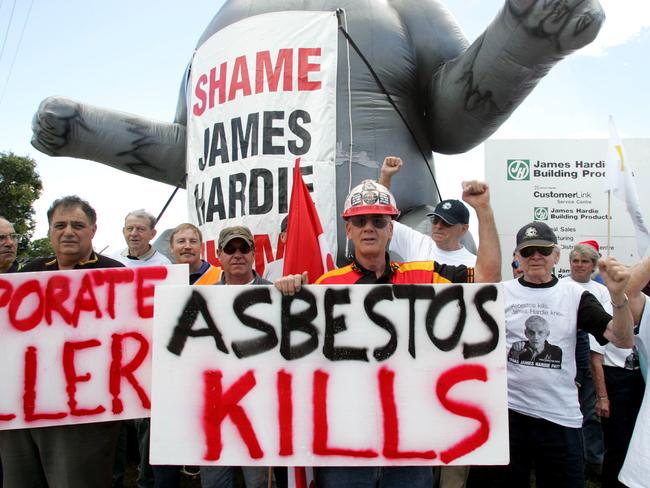

It’s been two decades since James Hardie was the most hated company in Australia, known for its association with deadly asbestos. Shareholders say that after an incredible sharemarket rehabilitation that propelled it into the rarefied air of world-class ASX businesses, it’s stitched them up with a wildly unpopular $14bn takeover.

James Hardie shares have lost $3bn and counting since it announced its “friendly” purchase of US rival Azek almost three weeks ago, at a 37 per cent premium to the target’s pre-offer price.

The Australian can reveal the deal comes with a record reverse break fee of $US272m ($450m) if it fails to complete. As if the price weren’t problematic enough, James Hardie has structured the transaction in a way that blocks Australian shareholders from having their say.

Investors are furious they’ve been circumvented from voting on the deal, and can’t call an extraordinary general meeting in time to fire the board because while it’s listed in Australia and loaded with superannuation funds such as AustralianSuper, James Hardie is domiciled in Ireland.

“There are bad acquisitions done in earnest, but I don’t think I’ve seen a more contrived acquisition as this,” says David Pace from Greencape Capital. Pace is not known for outspoken shareholder activism but says in 31 years he has never witnessed “such disdain for shareholders” than in this transaction.

The US is already James Hardie’s biggest market and it’s doubling down on the economy even as President Donald Trump pushes it closer to a recession. A recession would be doubly bad for James Hardie and Azek, which both supply building materials.

James Hardie will help fund the leveraged transaction by issuing new shares (35 per cent) and received a waiver from the ASX to avoid a shareholder vote. After the deal completes it will move its primary listing to the New York Stock Exchange.

“It’s a combination of not getting a vote, making an acquisition that is clearly uneconomic, board appointments that at best are questionable … it’s a fast-tracked way to make the New York Stock Exchange the primary listing, and with that comes lesser hurdles as it pertains to remuneration for executive management,” says Pace.

There have been few deals that the market has loathed as much as the James Hardie takeover of Azek. One was Perpetual’s takeover of Pendal, and before that, Wesfarmers’ top-of-market takeover of Coles.

But as anger mounts, US-based James Hardie chief executive Aaron Erter, who was paid $US21.7m last year, appears unapologetic.

Erter would not respond to written questions on whether he is a close personal friend of the chairman of Azek, Gary Hendrickson, or fellow Azek board member Howard Heckes, both of whom he previously worked with at US paint company Valspar, and both whom will now join the James Hardie board.

It has all the hallmarks of a boys club deal that puts personal connections ahead of shareholders, high-net-worth adviser Alex Pikoulas from Munjarra Capital believes.

“I feel like they’ve overpaid for this transaction and then we feel hoodwinked by the fact they’ve been able to get away with overpaying by getting around the requirements of a shareholder vote,” Pikoulas says.

Leaving nothing to chance, James Hardie buried its $US272m break fee on page 130 of one of four sets of documents released as part of the takeover announcement three weeks ago. It is 17 per cent higher than the previous record fee agreed on a deal twice as big: Square’s $39bn acquisition of Afterpay.

Due diligence

Azek shareholders will get to vote on the transaction and will not pay any break fee if the deal does not proceed.

It’s not just the sharemarket collapse that makes the deal less attractive by the day, but the apparent lack of due diligence around it.

Pace had owned James Hardie shares for more than 30 years, but sold down his position after grilling US-based chair Anne Lloyd and chief financial officer Rachel Wilson for more details and coming back unconvinced.

“When I pushed the chair on the type of due diligence they did there, she could offer up nothing specific,” says Pace. “They’ve spent a lot more time on the deal architecture than they have due diligence on this business. The CFO could not tell me what Azek’s cost base was. The CFO could not tell me the intangibles on its balance sheet. That’s extraordinary.”

Unfortunately for Australian shareholders who do not like the deal, there seems to be none of the usual recourse.

The ASX would not discuss on the record why it issued a waiver for James Hardie so that it could avoid putting the matter to a vote, but will rely on following the letter of the law in proceeding with a waiver under section 7.1 of the Corporations Act.

The ASX could still intervene if James Hardie applies for a foreign exempt listing, which it may not decide to do. And if it does not apply, Australian shareholders can still vote on executive pay.

James Hardie was advised in Australia by Jefferies and had Gilbert & Tobin as its lawyers on the deal. While both firms will benefit from a bump up the deal league tables from such a huge transaction, it will come with more scrutiny than usual.

Waiver notifications are made public by the ASX four-to-six weeks after a decision, and the James Hardie one is likely to become public in the next two weeks. It is unlikely to contain any detail.

“The ASX have clearly kicked an own goal here and could not put two and two together,” says Pace. “We don’t own ASX shares, but as a longstanding participant in this market, I’ll be lobbying very hard for their listing rules to be amended.”

Treasurer Jim Chalmers would not comment on whether there should be any government intervention or legal changes to preserve shareholder rights.

Veteran fund manager Geoff Wilson, the chairman of Wilson Asset Management, says James Hardie has “incredibly poor corporate governance”, and federal Labor should at least try to insert itself in the conversation.

“The government should stand up if they want to support corporate Australia and not let Australian companies disappear or move to America, even if the only thing they can do is name them and shame them,” says Wilson, whose WAM owns James Hardie shares.

“James Hardie is a public company in Australia that has an incredibly chequered history in terms of the asbestos problems years ago, and now they look as though they are trying to flout legislation, disregarding shareholders who (a) can’t vote on it, and (b) can’t vote the board out.”

The company has refused to answer questions on whether it would reconsider putting the deal to a shareholder vote.

Investors pointed to examples such as BHP demerging its secondary metals into a new company, South32, as an example of good corporate governance because it put the matter to shareholders even though it didn’t legally need to.

Wilson says that given Australian shareholders are being “disadvantaged” by the James Hardie deal, a regulatory response is warranted. “Whether the legislation has to be changed, or the ASX has to step up, or ASIC has to step up, or the government has to step up, someone has to,” Wilson says.

Pikoulas agrees that it’s time to hear from the government, although given the board and top executives are already based in Chicago, this may have little influence.

“At the very least, they should be on top of it and make a relevant comment, which might force the ASX into action,” Pikoulas says.

“This is a prominent Australian public company. Does the government have some sort of fiduciary duty in protecting the interests of shareholders of prominent Australian companies?

“Ultimately, yes, if not by decree, then by implication.”

For shareholders, this deal to buy Azek and subvert accountability is a reminder how not that long ago, the company tried to quickstep around paying victims of its deadly asbestos dust. The company stopped using asbestos in 1987. Back in 2001 James Hardie domiciled in the Netherlands as it became clear it would face a growing compensation bill from contaminated wall cladding, insulation and piping.

Chequered history

A NSW judicial inquiry found the move was not just for tax purposes, as had been claimed. The Netherlands happened to be one of only two countries where Australia did not have a treaty for the enforcement of civil court judgments.

As a result of that inquiry, the company bowed to public outrage and agreed to continue funding payouts through the Asbestos Injuries Compensation Fund. James Hardie said there would be no change to its commitment as a result of buying Azek.

“Our commitment to these communities is reflected in our ongoing support of the AICF – established in partnership with the NSW government in 2006,” said a company spokesman.

The firm has paid about $2.2bn to fund compensation payments to those affected by asbestos-related illnesses to date.

“James Hardie is a company that has a history of being too smart by half,” says Pikoulas. It “has a history of engineering seemingly smart behaviour that ends up coming unstuck”.

“The ASX also has a history,” says Pikoulas. “A very different history to James Hardie’s of being too clever and pushing it too far; the ASX has a history of tripping over itself.”

The securities regulator ASIC is currently reviewing how to make public markets more attractive and has put forward a question via a discussion paper about whether a sustained decline in listed entities would negatively impact the Australian economy. The answer, according to Wilson is clearly “yes.”

A shift of the 136-year-old firm’s primary listing from the ASX to the NYSE is also bad news for a shrinking exchange. “We’re on a fast track to looking like New Zealand, where you have liquidity in 10 stocks,” says Pace.

More Coverage

Originally published as The Azek takeover deal James Hardie shareholders can’t help but hate