Why 1% of Aussies are ruining it for everyone

As the PM does an about-face on the impacts of negative gearing, it’s revealed that one per cent of taxpayers own nearly a quarter of all Aussie investment properties.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ANALYSIS

Despite being used by less than 1.06 million Australians (or 4.1 per cent of the population) in the latest available data, negative gearing is a hotly debated issue and seen by many as political Kryptonite for governments and oppositions alike.

One of the key battlegrounds of the negative gearing debate over the past seven years has been the mind of now Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. In an appearance on Channel 9’s Today Show in November 2016, the then-Opposition Leader had this to say about the impact of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount:

“We’re in danger of developing a society where some people are able to buy their sixth, seventh, eighth home, but people trying to get into the market to buy their first home simply aren’t able to.”

"Australians know this is an issue for their kids & grandkids, they're being frozen out of the market" my comments on negative gearing pic.twitter.com/e8Xu7pZdAn

— Anthony Albanese (@AlboMP) November 25, 2016

Looking at the data from the ATO, 1 per cent of taxpayers own nearly a quarter of all investment properties across the nation. ATO figures, which cover up until the end of June 2021, revealed that there are almost 20,000 individual property investors who own six or more investment properties. It’s worth noting that this figure does not include investment properties held through various trust and corporate structures.

If we assume very conservatively that each of those individuals owns just six properties, not significantly more, that would mean that this cohort that represents 0.07 per cent of the population owns the equivalent of just under five per cent of total rental stock. For the snapshot taken in June 2021, 41.4 per cent of property investors in this group were negatively geared in aggregate.

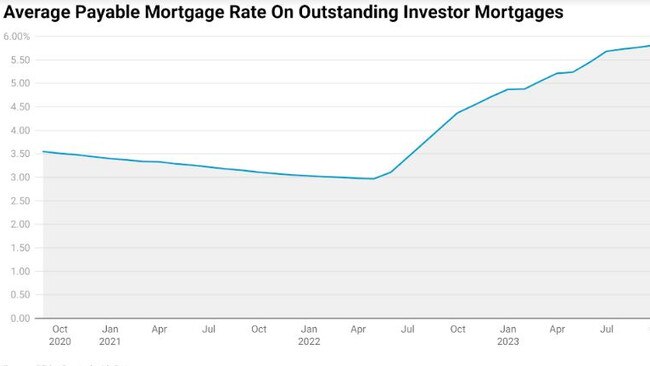

In June 2021, the average payable rate on outstanding investor mortgages was 3.22 per cent. As of the latest data from the Reserve Bank, the figure for that metric is now 5.82 per cent, an interest burden 80.7 per cent larger than it was a little under two-and-a-half years ago. For this reason, the number of property investors who are negatively geared is likely to increase significantly in the data for the current financial year.

Back to the future

In the present, the Prime Minister now has a very different perspective on negative gearing.

During the second leaders debate for the 2022 election, Albanese triumphantly declared that negative gearing is good.

This remains the policy stance of the Albanese government to this day, despite growing internal pressure within the federal Labor Party urging negative gearing reform.

But who was right about the impact of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese who fervently called for reform or Prime Minister Anthony Albanese who backs both policies?

In order to gain a quantifiable perspective on this question, we’ll be looking at several metrics comparing the challenge faced by those getting into the market in November 2016 – when Albanese made his assertion many first home buyers simply couldn’t get into the market — and today.

The repayment burden

Based on the benchmark three-year fixed mortgage rate, which is generally the lowest of benchmark rates across most long term timelines, the repayments on a median priced capital city dwelling with a 30-year mortgage in November 2016 was $26,876 per year or 35.9 per cent of the national median household income.

Based on these same settings, in 2023 the repayments would be $50,154 per year or 52 per cent of the national median household income.

Time to save a deposit

According to data from the ANZ-CoreLogic Housing Affordability Report, in 2016 it took approximately 8.7 years for the median household to save for a 20 per cent deposit on a median priced dwelling at a national level.

For the capitals it’s roughly 9.3 years to do the same, and 7.3 years in the regions.

Fast forward to 2023, it now takes 9.8 years to save for a deposit at a national average level, 9.6 years in the capitals and 9.7 years in the regions.

It is worth noting that these figures are from March, prior to a strong bounce in property values that have occurred in the months since.

However, if we go back to 2001, the start of the ANZ-CoreLogic data set for this metric, it took a significantly shorter amount of time to save for a deposit across all the assessed metrics.

A shift in urgency

Amid what some are calling the worst rental crisis in living memory, the urgency with which a prospective first-home buyer household wants to purchase a home has also been profoundly transformed.

At the time of Albanese’s appearance on the Today show in November 2016, the national rental vacancy rate was a very healthy 2.6 per cent, one of the highest readings in SQM Research’s more than 18 years’ worth of records.

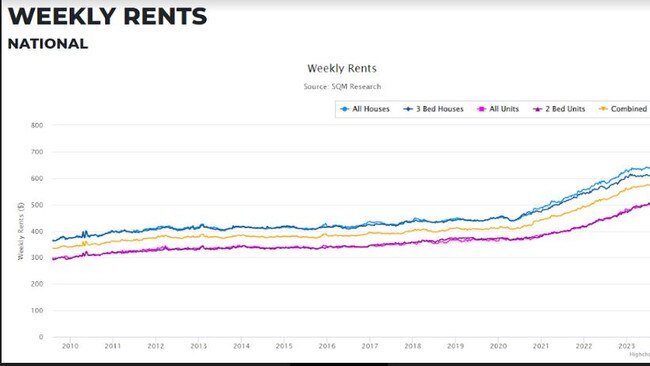

Meanwhile, asking rents at a national level had grown by just 1.31 per cent in the 12 months prior, reflecting a robust supply of rental properties in aggregate.

Today, things are almost the polar opposite.

The national rental vacancy rate is one per cent and multiple property providers say this is the lowest sustained vacancy rate in the history of their data sets.

As for asking rents for all dwellings nationally, SQM sees them up by 9.2 per cent in the last 12 months and up by 15.2 per cent in the nation’s capital cities.

These challenging conditions, which have seen even those with full time jobs miss out on rental accommodation and 1600 Australians become homeless each month, has led to a sense of desperation in some quarters to buy a property simply to escape the extremely challenging rental environment.

According to data from research firm Digital Finance Analytics, 14.7 per cent more rental households are planning to buy compared with this same metric in 2016.

In nominal terms, this means there are more than 58,000 rental households out there planning to buy a property at any given time compared with the proportion of renters planning to buy remaining the same as 2016.

While this doesn’t sound like much, in a housing market that saw less than 480,000 properties sell in the last 12 months, this is a significant increase in aggregate demand.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as Why 1% of Aussies are ruining it for everyone