‘Double whammy’ facing Aussie homeowners as interest rates soar while wages stagnate

It’s an argument older Aussies love to trot out again and again – but it’s only telling part of the story, and younger people have had enough.

Interest Rates

Don't miss out on the headlines from Interest Rates. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In the long history of Australian dinner table conversation, there are few topics that manage to elicit as much discussion and debate as the 17 per cent interest rates which defined 1989 and 1990.

This period marked the high-water mark of interest rates and also the beginning of a downtrend in the RBA cash rate which would continue until April 2022, during which it was slashed again and again from 17.5 per cent all the way to just 0.1 per cent.

While the tale of 17 per cent interest rates may be a hot button generational issue, it also provides a historic touchstone for the challenges faced by mortgage-paying Aussie households and raises some interesting questions.

As things currently stand, the four-week average for the ANZ Consumer Confidence Index is sitting at a similar level to the depths of the 1990-91 recession. During this period, the unemployment rate surged to over 10 per cent and deteriorating economic conditions saw business bankruptcies skyrocket.

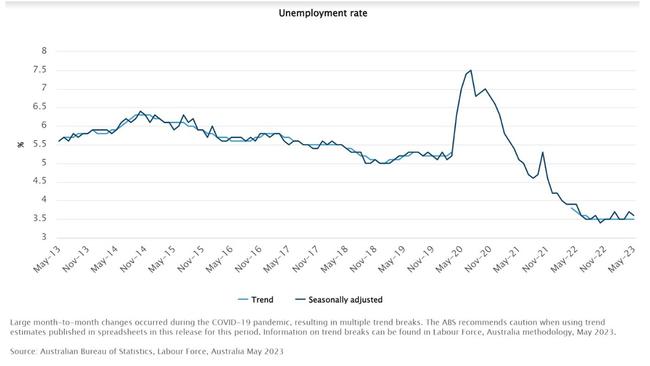

Yet despite today’s unemployment rate sitting near 49-year lows and the RBA cash rate at less than a quarter of what it was in 1990, households are just as downbeat about their economic and financial futures as during a recession which ultimately resulted in the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression.

One of the key parts of the puzzle is the large falls in real wages, which have seen the last 14 years of growth wiped out since inflationary pressures began exceeding wages growth in the June quarter of 2021.

With real wages growth already extremely weak prior to the pandemic, households may be acutely aware that getting their purchasing power back to where it was prior to the pandemic may take more than a decade.

While this loss in the value of the dollars in our collective wallets has hit all Australians, mortgage holders have faced a double whammy of falling purchasing power and rising mortgage servicing costs.

Explosion in household debt

Purely based on mortgage rates, at first glance, 2023 really doesn’t look too bad compared with the challenging days of 1990.

As things stand, the average payable variable rate on outstanding owner occupier mortgages is around 6.32 per cent, less than two-fifths of the headline mortgage rates at their peak a bit over three decades ago.

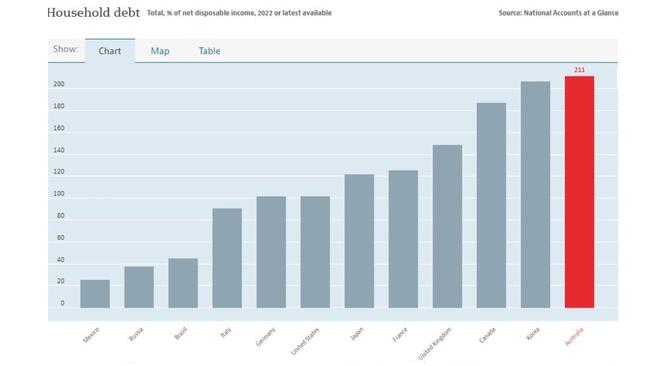

But what has changed dramatically in the decades since the era of 17 per cent mortgage rates is the amount of mortgage debt Australians hold.

According to data from the Bank For International Settlements, in 1990 household debt was under 50 per cent of household disposable income. As of 2021, that ratio had risen by more than fourfold to sit at 211 per cent of disposable income.

To put this figure into perspective, it is the highest of any developed G-20 nation and more than double that of the United States.

Debt service burden – 1990 v 2023

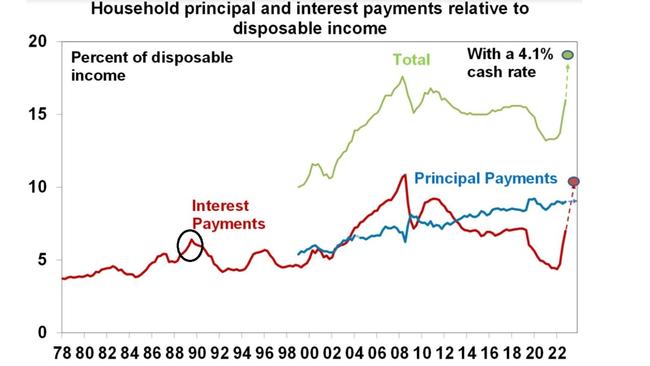

This chart from AMP’s chief economist Shane Oliver illustrates nicely how the burden of household interest repayments has evolved over time. The area within the little black circle on the graph below is the period during which mortgage rates rose from 13.5 per cent to 17 per cent. Yet despite the enormity of the burden 17 per cent mortgage rates placed on individual households, in aggregate terms the interest repayment burden was a fraction of what it is today.

Despite the explosion in household debt and the broadening of the number of households carrying this debt, prior to the beginning of the current rate rise cycle, households were spending the lowest proportion of their disposable income on interest repayments in 30 years.

With the advent of today’s 4.1 per cent cash rate, the burden of household debt interest repayments as a proportion of disposable income is nearing an all-time high.

Once principal repayments are factored into the equation, the overall burden of servicing Australia’s household debt load rises to the highest level on record.

An especially Australian problem

One of the at times under-appreciated aspects of the debate about interest rates is that the RBA is not necessarily all-powerful in deciding the course of monetary policy.

While it can set interest rates where it likes in theory, in reality there are other factors that must be carefully considered as part of the broader equation.

For example, the level of Australian interest rates also needs to be considered relative to the interest rates of other nations. If Australian rates were to fall too far behind those of the United States and its other peers, this would put downward pressure on the Australian dollar, raising the risk that currency weakness would add to inflationary pressures.

For the vast majority of the last 35 years, Australian interest rates have been higher that those of the US Federal Reserve, which is the global benchmark. This contributed to the relative strength of the Australian dollar throughout much of this period.

However, since November 2017, Australian interest rates have been equal or lower than their US counterpart. With inflation now an extremely serious issue for the first time in well over a decade, this has left the RBA in a challenging position.

On one hand, it has to balance the strength of the Australian dollar against the relative level of the cash rate compared with its peers, while on the other, be mindful of the extremely large debt load of Australian households and the generally variable nature of Aussie mortgages.

With recent data showing robust job vacancies, a still near 49-year low unemployment rate and a lack of a credible swift path to its 2-3 per cent inflation target, the RBA has its work cut out attempting to reduce inflation without causing a recession and driving highly indebted households to the wall.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as ‘Double whammy’ facing Aussie homeowners as interest rates soar while wages stagnate