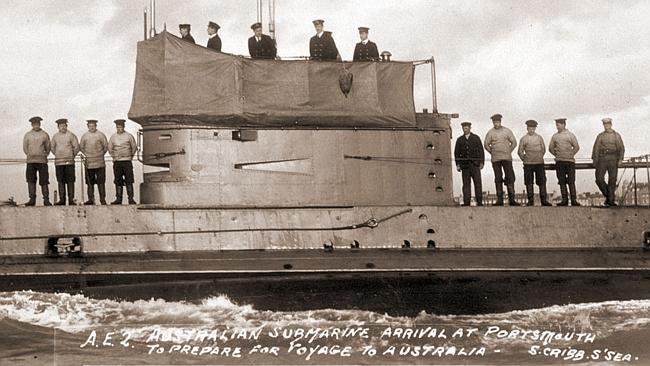

MISSION: Impossible. Every submarine attempting to pass through the Dardanelles had been sunk. But could an Australian crew and their irreverent Irish commander turn the tide of a disastrous war?

The grand adventure of World War I had by 1915 already degenerated into blood, mud, sweat and tears.

For the crew of Australia’s only surviving submarine, AE2, their war was a quieter one — fought among the currents and sandbanks of the fast-flowing Dardanelles passage. But it was no less intense.

AE2 was virtually blind. Its batteries were limited. The currents were confused. To surface was to invite a blistering barrage of gunfire. And the scrape of metal meant the high explosive of a mine was dangling nearby.

All the while the crew knew their comrades in arms were staining the cliffs and shores of Gallipoli with blood just a few short miles away.

So they pressed on, against insurmountable odds.

If they could just get into the protected Marmara Sea. There they could “run amok”, sowing the seeds of confusion among the warships lobbing their huge shells over the peninsula and on to the ANZAC’s heads — as well as choking the supply of men, equipment and ammunition rushing across the waters as reinforcements.

Several times previously allied submarines had tried to breach the mazelike Dardanelles. Each time the French and British boats had been rebuffed. Quickly, it became accepted that it was a mission outside the scope offered by this new form of naval warfare.

But the little Aussie sub’s captain and crew were not established thinkers.

Time and again Lieutenant Commander Henry Stoker of AE2 approached his superiors: He had a plan.

Eventually, after a string of humiliating defeats, the Royal Navy capitulated. He could give the heavily defended passage one last go.

They had nothing else to lose.

And so it was that, at a critical point of the Gallipoli campaign, Stoker’s radical ideas and calculated courage would prove insurmountable odds could be overcome.

But AE2’s achievements were quickly relegated to obscurity.

The Admiralty’s Lordships guaranteed the British captains who had followed the trailblazing AE2 a place in history with awards of the Victoria Cross.

Stoker, despite being promised the world, was deemed a mere competent amateur. The “impossible” success of AE2 and its provincial crew on April 25, 1915, was mildly acknowledged with the far less grand Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

If there’s one thing their Lordships loathed, it was a smartass. Especially if he was right.

Lieutenant Commander Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker (above right). An Irishman in command of an Australian submarine? And a cousin of Bram Stoker — the famous author of Dracula — at that?

In the incredibly class conscious Royal Navy of the time, it was a scenario likely described in polite circles as “quaint”.

But it was a bias the shabbily-clad lad from Dublin had been struggling successfully against since age 12 when he persuaded his father — a doctor — to allow him to attend a naval school

Stoker’s secret weapon? Humour.

He soon established a reputation for irreverence. But this wit was balanced by his inclusive quest for a good time. He was also an avid sports lover.

In officer school, his competence shone through — despite the institutionalised bias.

Stoker worked hard. But he also played hard. This was very difficult to do on a young officer’s wage.

The newly formed submarine service offered to double that sum. But “danger money” was appropriately named: Fatal accidents abounded.

Stoker volunteered anyway.

When the 28-year-old officer was given the newly completed Australian submarine in 1913, he found it to be absolute state-of-the-art.

“I seemed amazingly lucky to get such a command then,” Stoker wrote, “the latest and by far the largest submarines (we) had produced. Only five of them were completed when I got my appointment, and all were commanded by men greatly senior to me.”

The E-class had four torpedo tubes and eight torpedos — but no gun. Capable of covering 15 nautical miles an hour (knots) on the surface, her electric motors could push through the water submerged at nine.

They were impressive figures for the time.

But there was little doubt as to the level of comfort — or lack thereof — the 54m long boat offered.

Most of Its crew of 32 would share sleeping pallets placed among the torpedoes. The three officers shared two tight bunks. There was one crude toilet and the only sanitary facilities was the odd bucket.

The conditions were “character building”. But the extra cash was good.

The war had not been going well.

The might of the British Empire was bogged down in the trenches of Europe.

April 1915 opened to AE2 — and her crew — being dry-docked in Malta.

A misplaced harbour light had led AE2 astray on the dark night of March 17. The Dardanelles Patrol’s only advanced submarine was driven on to rocks.

Such an event was a humiliation for any captain. That it had happened on St Patrick’s Day would have left Stoker open for even more ribbing than usual.

And so it was that AE2 missed First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill’s greatest blunder by only one day: On March 18, his seemingly insurmountable fleet of battleships was smashed by Turkish guns and mines as it attempted to force its way up the Dardanelles channel.

It was the outcome of Churchill’s grand plan: He could break the stalemate in the trenches of France. His navy could seize the Turkish capital, Constantinople, capture the Gallipoli peninsula and enable a force of men to join the Russians to open a second front against the Germans.

How was merely an inconsequential detail that could be sorted out by those at the scene.

The peerless Royal Navy, after all, ruled the waves. And Churchill’s pedigree was sound.

What could possibly go wrong?

It was an unmitigated disaster. The inspired strategy to compel the Turks to surrender lay in ruins on the Dardanelles seabed.

There was only one option left to save the Empire’s pride: Send in the troops.

Salt was rubbed into Stoker’s wounded pride when three big new E-class submarines — E11, E14 and E15 — dropped in on Malta on their way to reinforce the Dardanelles Patrol.

His patrol.

AE2’s chances of winning the chance to sneak through the treacherous waterway seemed less likely than ever.

“It idly crossed my mind to wonder what fate had in store for the four commanding officers,” wrote Stoker. “Two months later I knew the answer. It was death for one; three and a half years of living death for another; and Victoria Crosses for the other two.”

As the crew of AE2 finally set about packing their belongings on their patched-up submarine, news came through of just such an attempt.

The newly arrived British submarine E15 had been forced aground by strong currents inside the Dardanelles. The captain was dead. Six of her crew had been killed by cannon fire. The rest were captured. The Turks were swarming over her battered hull.

Lemnos harbour was a hive of activity. Battleships. Troop ships. Supply ships. All were crowded into the sheltered waters in preparation of the Gallipoli ground invasion.

Like Churchill, Lord Kitchener — supreme commander of the Empire’s army — was brash with confidence: “Suppose one submarine pops up opposite the town of Gallipoli and waves a Union Jack three times, the whole Turkish garrison on the peninsula will take to their heels …”

It was just such an opinion that his subordinate Sir Ian Hamilton brought with him as commander of the British, Australian and New Zealand divisions allocated to the invasion.

The Royal Navy’s commanders at the scene were more hesitant. Risking more valuable surface ships was out of the question. And the submarines had proven inferior to the task.

Had they?

Captain Stoker argued emphatically that they had not.

Early on April 23, the admiral of the Dardanelles patrol summonsed the young commanding officer of AE2 to his flagship, the battleship Queen Elizabeth.

Stoker wrote of the admiral’s hesitance: “He found it difficult to believe the feat was possible, but its military value would be so great it must be tried … If we got through, other boats would immediately be sent to follow.”

Yes, Stoker replied. Navigating the Narrows of the Dardanelles virtually blind was a perilous proposition. Yes, the masses of guns and mines presented a seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

But such opposition was to be expected. And AE2’s stay in Malta had seen her fitted with cables designed to divert mines away from her hull.

It was the maths that was the killer.

AE2 could travel at 15 knots (28kph) on the surface and nine (17kph) beneath. Then subtract the force of the prevailing current, which was about 5 knots (9kph).

Speed, however, wasn’t the issue. It was endurance.

In optimal conditions AE2 could travel 80km underwater on battery power before it had to surface and use diesel engines to recharge. A clean course through the Narrows of the Dardanelles was 75km. Against the onrushing current and with the imperative of dodging mines, the equivalent distance needing to be travelled quickly bloated to beyond 100km.

Under the guns of the Turkish forts, this was suicide.

But Stoker had heard of eddies where the waters of the Dardanelles swirled back up the channel. Perhaps he could hitch a ride on one of these? Also, experience had shown the main current slowed the deeper one went.

He could keep his precious batteries charged by travelling as far as possible on the surface by night. He’d save the 80km the batteries could travel for daylight and diving beneath the minefields. If things got tough, he’d simply sit on the bottom and wait it out.

The admiral was impressed: “If you succeed, there is no calculating the result it will cause and it may well be that you will have done more to finish the war than any other act accomplished.”

It was a rush to get ready. But Stoker took time on April 23 to address his crew.

Any man who wished to stay behind, could.

This would be a volunteer’s mission only. Nobody who remained would be ill thought of.

West Australian mechanic Charles Suckling summed up the crew’s feelings for their irreverent captain: “I would like to state now that Lieut. Com Stokes was a man absolutely loved by his crew, and there was not one of us who was not willing to go anywhere he cared to take us … Not one man asked to be relieved.”

Within two hours they were packed. The crew even had time to write last letters home. Captain Stoker stashed aboard an over-sized White Ensign. If he got through the Narrows, he wanted to make sure the Turks knew.

Soon AE2 sat at the mouth of the Dardanelles waiting for the moon to rise. Its soft glow would be a necessary guide for the surface run up the strait to the edge of the first minefield.

Searchlights flickered in the distance. Behind them, the crew knew, lay the dark-grey muzzles of Turkish cannons.

Lady luck seemed to smile.

The closest searchlight just inside the entrance suddenly went out. Then another key light went out.

AE2 glided carefully along the darkened surface near the western shore. Stoker had been right: He’d found a strong eddy and was being drawn further up the Dardanelles passage than he’d dared hope.

Then, a Turkish searchlight suddenly switched on.

To stay on the surface meant certain discovery.

Stoker ordered AE2 to dive.

“And then — oh moment ripe — an accident happened,” Stoker would write.

“The shaft which worked the foremost diving rudders broke! Impossible to mend under several hours’ work, impossible to dive, impossible to go on — we must go back! Go back! Ye Gods!

“After all the working up to this moment; with a work before us that might have a bearing on the finish of the war; a chance of a lifetime — no of centuries of lifetimes — before us, and we must turn back! The hills and mountains of the Dardanelles echoed and re-echoed with the ironical laughter of that cursed Goddess of Fortune.”

But fortune hadn’t completely abandoned AE2 and her crew.

The little boat managed to thread her way back between the searchlights and guns to escape the Dardanelles before dawn.

It took until noon to repair the damaged machinery.

Stoker and AE2 sat at their anchorage mulling their mission as the mighty battleship Queen Elizabeth hove into view. On board was the admiral.

He was told an attack on the beaches of the Gallipoli beaches was just hours away. AE2’s mission, if anything, was even more critical now.

“Try again tomorrow,” the British admiral said. “If you succeed in getting through there is nothing you could possibly want that we won’t do for you.”

Promises, promises.

But there was a catch.

Now AE2 — on top of proving it was possible to pass through the Narrows — had to “run amok” among the Turkish shipping there.

An impossible mission had just been turned into a suicide mission.

“If you searched the whole world over I doubt you would find a much more unpleasant spot to carry out a submarine attack than this Narrows of Charnak,” Stoker wrote. “It is certainly not an ideal place for manoeuvres in a slow-moving and difficultly turned submarine …

“However, we were either going to get through or else we were not, and at this stage an extra difficulty or so did not make very much matter.”

At 2.25am, on April 25, AE2 again attempted to breach the Dardanelles.

The water was dead calm. The moon was bright. The Turkish searchlights were active.

“Each time, as a beam of light touched the AE2 with brighter and yet brighter fingers, one held for the instant one’s breath, lest the steady sweep … would show a suspicion of our shadowy presence,” he wrote.

Again Stoker found the eddy in the channel which would boost the submarine along its way.

Again, boat and crew risked discovery by staying on the surface as long as possible, with only the darkness as their shield.

KABOOM.

A cannon shell buzzed past Stoker’s head has he stood on the small conning tower.

But he knew AE2 had made it far enough up the channel. With batteries fully charged, the first minefield lay just before him.

Now it was time to dive deep and put his faith in his 30-year-old charts and the navigation skills of his officers. AE2 was blind. She had to stay below periscope depth to avoid the mines.

Stoker also anticipated a deep water countercurrent would suck AE2 up the channel.

“The rappings and scrapings on the hull of the boat by the mooring wires of the mines … seemed almost damnably continuous,” the commander wrote.

It was an understatement. The tension aboard was terrible.

Dead reckoning was an ominous navigation term — especially when any miscalculation meant running aground under the muzzles of massed Turkish cannons.

Stoker judged the risk too great. Twice he raised the submarine — and its periscope — amid the minefield.

The third time was a surprise.

Through AE2’s periscope was the distinctive “elbow” of hills which formed the previously impassable 2km wide Narrows and forts of Chanak. The legendary Dardanelles passage lay just a few hundred metres away.

No submarine had yet made it so far.

The deep water current Stoker had gambled upon had proven more powerful than he had thought.

Under the silver moon, the dead-calm sea was like a mirror. AE2’s periscope stood out like the proverbial.

Instantly, Turkish cannon began lobbing shells down upon the still submerged boat.

“The shock of projectiles striking the water overhead caused subdued thuds in the submarine,” a laconic Stoker wrote. “Around the top of the periscope, the water, lashed into white spray, caused a curiously pretty effect — but added little to the ease of taking observations.”

Mindful of his orders to attack, Stoker kept an eye out for targets in the narrow waterway.

He didn’t know it then, but AE2 had already made a significant contribution to the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli cove. A Turkish battleship had been lobbing shells over the peninsula, raining down accurate death and destruction on the ANZACs struggled ashore. Suddenly, it ceased.

Reports of a submarine at the Narrows had caused the warship to run for the safety of its home port.

Stoker spotted another battleship at Chanak. An old one. Perhaps it was being used to launch mines?

Then a cruiser emerged from behind the hulk.

It was exactly the sort of thing Stoker had been hoping for.

With a destroyer racing in to ram the submarine, Stoker fired a torpedo. As soon as the projectile left its bay, AE2 dived for safety.

“A last glance as the periscope dipped showed the destroyer apparently right on top of us, and then, amid the noise of her propeller whizzing overhead, was heard the big explosion as the torpedo struck.”

Attempting to pass through the stranglehold of the Narrows without even using the periscope for a few valuable glimpses of land proved impossible.

AE2 ran aground.

The incline of the eastern shore caused the boat to slide upwards, leaving AE2’s conning tower clearly exposed. The forts of Nagara directly above and nearby warships all began venting their fury.

“As I looked,” Stoker wrote “one of the guns fired, apparently right into my eye, and seemingly so close that I involuntarily jumped back.”

For five minutes the crew struggled to get their boat off the sand bank. Only the fact AE2 was so close to the enemy saved them: The Turkish guns could not aim so low.

Suddenly AE2 slid off.

But the current was pushing her back down the channel.

Propellers whirring, AE2 attempted the nautical equivalent of a U-turn.

The submarine ran aground again — this time on the opposite shore!

“A quick glance around showed a gunboat and some destroyers, little more than a hundred yards off, blazing hard with all their broadsides … and then, best of all, a clear view up the strait showing that if we could only get off we were heading on the correct course.”

The submarine shook. Groaned. Screamed.

Then, after about four minutes on the surface, two great bumps marked AE2 toppling back into deep water.

My a miracle, the submarine had not been hit. AE2 inched up the channel, aiming for Nagara Point and the widening of the waterway it represented.

Hunted by Turkish destroyers and being forced to navigate by little more than guesswork, AE2 managed to make its way towards the Marmara Sea.

But the Australian submarine was unable to shake its pursuers.

“The damnable calmness of the water did not permit even the shortest spell of observation without the periscope being seen,” Stoker remarked.

Now for the next part of his plan.

Wait the enemy out.

AE2’s batteries were almost depleted. Turkish warships swarmed overhead.

So Stoker set the submarine down on a sandbar some 21 metres below the surface and ordered his crew get some rest.

It was only 8.30am.

It would be a long wait until nightfall.

The air, already fouled by diesel fumes, grew steadily staler. The humidity was rising.

Sleep proved impossible: Warships constantly crossed overhead.

So Stoker decided to move.

But AE2 didn’t respond.

Instead, the battered submarine entered an uncontrolled slide down the sand bank.

Her descent finally stopped. How deep, the crew did not know. It was well below the 30 metre “crush depth” their dive gauge showed.

Using some of the submarine’s precious compressed air, the excess water that had leaked into the dive tanks since AE2’s rough groundings earlier that morning was expelled.

Slowly, AE2 inched back up to a safe depth. Here Stoker chose to remain until darkness fell.

“Have you ever known time to move more slowly?” he wrote. “Percival (the nickname given to the Turkish warship hunting them) passed and repassed at steady intervals … The few moments immediately after his passing were the bad ones. If any sweep he was dragging after him caught us, the side of our boat would be blown in on us very soon afterwards … I … confess to a feeling of quivering funk each time he passed overhead.”

After 10 hours of hunting, the Turks gave up.

Two hours later, Stoker decided to surface.

Humidity steamed out of AE2’s opened hatches as the crew surged upwards for fresh air. The cool night breeze brought blessed relief.

Stoker immediately ordered the admiral aboard Queen Elisabeth be signalled: AE2 had made it. More submarines could come to attack Turkish shipping.

But there was no reply. Obviously the radio had a fault. The crew could only hope the message would be received.

It was.

It had arrived at a critical moment.

Aboard the flagship, a crisis meeting was in progress. The landings had not gone as expected.

Amid the flurry of disastrous reports came one piece of good news: AE2 had achieved the impossible.

General Sir Ian Hamilton was reportedly enthused. A submarine had waved the White Ensign behind Turkish lines. Surrender, no doubt, would soon ensue?

“It is an omen,” the naval Chief of Staff reportedly said, “An Australian submarine has done the finest feat in submarine history and is going to torpedo all the ships bringing reinforcements, supplies and ammunition into Gallipoli.”

He then committed the ANZACS to 10 months of hell, clinging to the cliffs of Gallipoli Cove

Stoker and his crew set about obeying their orders. It was time to run amok.

For the next few days AE2 sought and engaged targets of opportunity.

They were few and far between. The presence of a hostile submarine in narrow waterways was too much of a risk. The vital supply and troop ships remained moored. Reinforcements were restricted to smaller, faster vessels.

It was the inestimable victory his admiral had asked for.

AE2 continued its game of cat-and-mouse with its Turkish gunboat pursuers. Then, on April 29, she sighted another submarine.

“Yes! No! Yes! E14, by all the gods!”

Stoker was relieved. His message had got through. Now, so had E14.

Together they plotted a raid on Constantinople.

But AE2’s luck had run out.

When attempting to rendezvous with E14 the following day, Stoker ordered a dive when the smoke from an approaching Turkish warship — the Sultanhisar — was spotted.

“Not a suspicion of impending disaster lay in our minds,” Stoker wrote.

Suddenly, while attempting to level off at 15 metres, the Australian submarine went out of control. The bow rose of its own accord.

“All efforts at regaining control proved futile. The diving rudders had not the slightest effect …”

AE2 broke surface like a breaching whale.

In full sight of the Turks.

“Through the periscope I saw a torpedo-boat a bare hundred yards off, firing hard. At all costs we must get under again at once.”

AE2 dived again.

Again, Stoker attempted to level the submarine off at 15 metres.

This time AE2 refused to respond.

She kept diving.

Steeper and steeper she went down.

She quickly passed the theoretical 30m depth limit.

“We could not tell to what depths she was reaching,” Stoker wrote.

With the engines powering full astern, AE2 finally stopped.

“There came a cry from the coxswain: ‘She’s coming up, sir!” and the needle seemed to jerk itself reluctantly away from the 100-feet mark, and then to rise rapidly.”

AE2 again burst through the surface.

As the captain attempted to assess the diving tanks, the officer at the periscope reported a second gunboat approaching.

“Under we must get again — and away we went with the same terrible inclination down by the bows … desperate attempts to regain control. But down and down and down she went, faster even than before.”

Eggs toppled from their holders. Bread fell from shelves. Knives, forks and plates slid from their racks.

“Everything that could fall over fell; men, slipping and struggling, grasped hold of valves, gauges, rods, anything to hold them up in position to their post.”

Death seemed imminent.

“In Heaven’s name, what depth were we at? Why did not the sides of the boat cave in under the pressure and finish it?”

For a third time AE2 changed her mind and surged to the surface.

WHAM.

This time the Turks had been waiting.

As the submarine’s stern lifted high out of the waves, a Turkish shell slammed into the exposed engine room.

The pressure hull had been breached. Then two more hits.

AE2 was done for.

“Finished!” Stoker exclaims. “We were caught! We could no longer dive and our defence was gone. It but remained to avoid useless sacrifice of life. All hands were ordered on deck and overboard.”

As the crew scrambled overboard, Stoker and his officers calmly ensured the submarine would now sink for good — taking her secrets to the bottom.

“But through the conning tower windows I saw there was still a minute to spare. I jumped back down again and had a last look round — for, you see, I was fond of AE2”.

But soon he was forced to jump overboard.

“Perhaps a minute passed, and then, slowly and gracefully, like the lady she was, without sound or sigh, without causing an eddy or a ripple on the water, AE2 just slid away on her last and longest dive.”

The war was over for Stoker and his crew.

West Australian engine room rating Charles Suckling summed up their fate: “Then began a life for us which was nothing but a sorry existence, and I don’t think, if we had known what was ahead of us, that one of us would have left the boat. And when we were released from Turkey three-and-a-half years later, leaving four of our number behind, we were nothing more than living skeletons.”

But that’s another story — and you can read more from Charles at AnzacLive.

AE2 sat, almost forgotten, on the seabed for almost a century.

The tale of her success was lost amid the courage and chaos of her kinsmen ashore at Gallipoli Cove.

The British admiral never fulfilled his promises to Stoker and the submarine’s crew.

Only when the amazingly intact wreck of AE2 was discovered again in June 1998, would the story of the “Silent Anzac” once again emerge from the murky waters of history.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

FBI warning as Israel reveals how it will mark October 7

A chilling message has been issued as Israel prepares to mark the grim anniversary of the attack that changed the world. See the photos, video.