The Petrov Affair: New details emerge in Australia’s most famous spy defection case

ASIO director general Mike Burgess explains why espionage is not “romantic game”, on the 70th anniversary of Russian KGB agents Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov’s defection to Australia.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EXCLUSIVE

She was charming, intelligent, fit. A pretty honey blonde who loved nothing more than a walk on the beach, a swim in the local pool.

Her husband loved to hunt and fish, and “disappear” injudiciously for a few drinks down at the pub.

They could have been the quintessential Australian couple, but they were in reality the most famous Russian spies in Australia history.

This week is the 70th anniversary of those Russian KGB agents Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov’s defection to Australia. It was a patching-over said be so significant that spy chiefs credit it with bringing together what is now known as the Five Eyes intelligence alliance. It put the fledgling spy agency ASIO on the world map.

But it’s just weeks ago the file was finally closed on CABIN-12 the super-secret spy operation which was launched to turn the Petrovs, in what became sensational front-page news around the world.

And with the final chapter comes intimate new details and photos of their domestic lives after their defection, as their ASIO minders reveal what it was like living with, getting to know and taking care of the Petrov’s behind closed doors in secret locations from Sydney to Queensland and Victoria.

The anniversary comes at a time when the current ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess has warned spies targeting Australians are more active than ever, and that an unnamed Australian politician had been recruited by a foreign government while in Parliament.

Mr Burgess said this week that the defection and the drama surrounding the Petrov affair “should serve as a real reminder that espionage is real and is not some romantic game – the stakes are dangerously high.

“The planning of the operation took years and the dividends lasted decades. The intelligence supplied by the Petrovs’ helped Western intelligence agencies identify hundreds of Soviet operatives around the world, as well as providing invaluable insights into Russian tradecraft,” Mr Burgess said.

The defection of the Petrovs was a huge victory for the fledging ASIO and a defining moment in Australian history. It severed diplomatic relations with the USSR for decades and sparked the Royal Commission on Espionage.

It was the height of the cold war in 1954. Mr Petrov was consul and third secretary at the Russian Embassy in Canberra and Mrs Petrov, was officially a clerk and accountant. But ASIO had discovered they were really undercover KGB officers.

After years of ASIO agents building a relationship with Mr Petrov, and in the wake of the death of Stalin and the arrest and execution of the then head the KGB, Mr Petrov accepted an offer to defect, without telling his wife.

While Mr Petrov was kept in an ASIO safe house in Sydney, Mrs Petrov was held inside the Russian Embassy unaware if her husband was dead or alive until “couriers” from Moscow arrived to take her back to Russia.

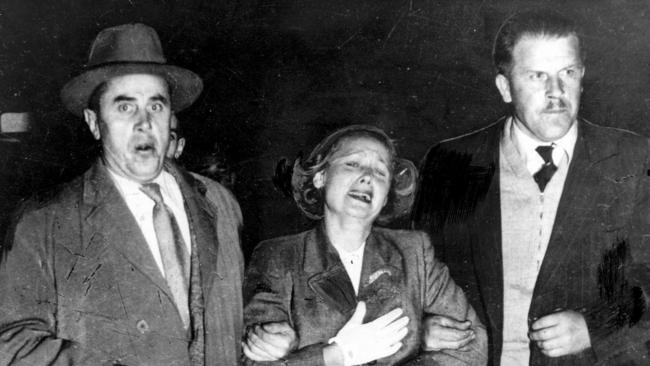

The most famous photograph from the time showed two Russian henchmen roughly dragging Mrs Petrov, missing a shoe, to a plane at Sydney airport, sparked outrage and protests against her “kidnapping”.

The Russians succeeded in getting Mrs Petrov on the plane in Sydney but when it stopped to refuel in Darwin, ASIO got a message to her through the pilot offering her asylum which she accepted.

Over the next two years the Petrovs gave valuable intelligence to ASIO including about British diplomats who had spied for the Soviet Union.

Jack Griffith, an ASIO officer known as a “49er” because he was with the agency when it began in 1949, was assigned to visit the Petrovs during the 1970s. He remembered them both having “phenomenal memories”.

“I was Petrov’s man for years,” he said. “I knew he had whole code books in his head.”

ASIO has opening up about some of the details of the Petrovs’ lives in Sydney, in Queensland where they lived with a married ASIO couple Dudley and Joan Doherty, and ultimately with new identities in Melbourne.

There are never-before-seen photos of the couple together, and on fishing trips with secret agents assigned to keep them busy.

Snapshots of accounting ledgers show what ASIO was spending on the Petrovs while they were in hiding, including buying them bottles of whiskey, beer, wine and, cigarettes. There are also entries for toothpaste, tooth brushes, razor blades, bath towels and carpets. The ledger shows entries for rent paid, and rail fares between Sydney and Melbourne.

Details have emerged on how Mr Petrov, known to like a tipple, sent ASIO into a panic after disappearing from a Sydney safe house to “go for a walk”.

The late ASIO agent Les Scott, also a 49er, who spent a lot of time with the Petrovs’ documented his memories for posterity, especially remembering having to retrieve Mr Petrov after his vanishing act.

“He flagged down a delivery van and our (ASIO’s) brief was to know where he was, but to not restrain him,” Mr Scott said.

“I was the one to follow him. The delivery van let him out, and I was able to get him into my car by coming alongside and just opening the door, and he thought I was another kind motorist.

“We went to Manly and went into a hotel – he was drinking on his own which allowed me to make a call to the office. We had no radio and public telephones were few and far between, and it seemed an eternity before somebody came to assist me. So we managed to convince Petrov to come back to the safe house.”

After the Royal Commission into Espionage at which the Petrovs gave evidence, they were given citizenship and lived in the Melbourne suburb of Bentleigh and worked under their new identities as Sven and Maria Allyson.

Mrs Petrov also did voluntary work for Meals on Wheels and Mr Petrov enjoyed Australian Rules football, hunting and fishing.

They were assigned an ASIO agent, Robin Knight, to be their case officer and he was to take care of them for the rest of their lives.

Opening up about his relationship with the Petrovs, Mr Knight said he became quite friendly with Mrs Petrov over the years.

“Mrs Petrov lived, I’d say, a fairly normal life. She had friends, she kept herself very fit, she loved to go down to St Kilda and walk on the beach, that sort of thing. When I first met her she’d go to the pool every day and go swimming,” he said.

“Mrs Petrov was very interested in the Australian democratic political process, and television coverage on election night was one of her favourite night’s viewing.”

“I found her intelligent, sociable and she always presented well. She was determined and forthright, yet charming to meet.”

Mr Knight visiting at least one a month, and when Mr Petrov suffered a stroke and had to live in a nursing home and Mr Knight arranged “the best that could be done”.

After Mr Petrov’s death, Mr Knight helped to bring Mrs Petrov’s sister Tamara to Australia.

He said it took a bit of effort to convince the Russians to let her leave.

“We just didn’t know quite what to expect, whether the Russians would still take an interest in her,” Mr Knight said.

“We had it all planned out when she arrived at the airport. We had a Russian translator there and a couple of ASIO officers to usher her through customs, it was pretty emotional when they both met after 41 years.”

After the death of Mrs Petrov in 2002, Mr Knight arranged her funeral and his last act before closing the Petrov file was organising the continual maintenance of a memorial plaque at Springvale Crematorium.