Prison officers reveals chilling moment colleague was dragged into cell by Anita Cobby’s killer rapist

‘Trixie’ Bennett-Hillier came into close contact with Anita Cobby’s killer, who once tackled a female prison officer and tried to drag her into a cell. WARNING: Graphic

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Beatrix ‘Trixie’ Bennett-Hillier knew that if she wanted to survive, she couldn’t think about what these blokes had done.

As a correctional officer, her role was to be impartial, professional, kind but firm.

But somehow, when she looked at Anita Cobby’s killer, she couldn’t help but hate.

In February, 1986, John Travers led a gang of five men in the brutal rape, torture and murder of nurse Anita Cobby.

A former beauty queen, Anita, 26, was walking home through Blacktown, Western Sydney, when Travers, the three Murphy brothers - Michael, Gary, and Leslie - and Michael Murdoch dragged her screaming into a car.

Over a period of two hours, Anita was raped and beaten, before Travers’ slit her throat.

For Bennett-Hillier — as for the many Australians who crowded the court to berate the ‘animals’ — the crime felt personal.

As a local, Bennett-Hillier knew it could have just as easily been her daughter, her friend, her loved one.

And here Travers was, quietly living his life, albeit between prison walls.

That didn’t seem like justice.

When Bennett-Hillier first came across Travers, she was working as the “phones officer” at notorious Goulburn Maximum Security.

The prison was known to be dangerous, but as an aspiring female officer in a male-dominated industry, it was the only place she could get a job in the late 80s.

“No one else wanted to go there!” she told On Guard.

Inmates would arrive at her office to make their allocated phone calls.

“Well, Travers would come up for his phone calls and I’d pretend to dial the number,” Bennett-Hillier, recalled, with a wicked smile.

“I never let him go through.”

“Geez, sorry about that, mate. Looks like no one’s home. Funny about that,” she’d say, a little too gleefully.

She may have had the upper-hand but Bennett-Hillier knew to keep her wits about her. Even in prison, Travers was dangerous.

The grandmother-of-six recalls one particularly chilling incident, circa 1992.

It was early one morning and a pretty young officer was doing her ‘let-gos’ (letting the prisoners out of their cells after the night).

“He must have heard her voice or something and knew she was coming because when she opened the door, he pulled her into the cell,” Bennett-Hillier said.

“He kind of tackled her and tried to drag her in. Luckily there was an officer close by, so she was looked after before he could do much …

“This girl wasn’t allowed to go anywhere by herself. She was too pretty, too pretty for prison. I don’t think she lasted much longer after that.”

Soon, Bennett-Hillier had her own close call involving another killer, Stephen Wayne ‘Shorty’ Jamieson.

Jamieson was one of five homeless youths who raped and killed 21-year-old bank teller, Janine Balding, abducting her from the Sutherland railway carpark in 1988.

Separated by just a couple of years, Janine and Anita’s murders are often linked as shocking attacks of sexualised gang violence that forever changed the way female Sydneysiders perceived their safety.

“I couldn’t stand the sight of his head,” Bennett-Hillier said.

“I just couldn’t do anything for him. Every time he’d ask me for something I’d say, ‘go away’.

“Anyway, he didn’t like me and one day this inmate who had my back came and told me, ‘Miss, you better be careful. Jamieson’s after you’.”

‘Make my day,’ Bennett-Hillier recalled thinking.

Not long after that, she was walking through a yard when she noticed the same inmate suddenly appear beside her.

“He came beside me and I saw his arm go behind my back, like a barrier.”

When Bennett-Hillier turned around, there was Jamieson close behind her.

It was then she realised she’d only narrowly escaped Jamieson’s grasp, thanks to the other inmate’s intervention.

“This guy put his arm between Jamieson and me, like he was protecting me.

“(Jamieson) probably would have tried to smother me,” she says.

“You’re at risk like that all the time in prison, no matter what you do.”

NOW, THEY WANTED BLOOD.

Beatrix ‘Trixie’ Bennett-Hillier looked at the man’s figure lying on the asphalt at Goulburn Maximum Security Prison.

A mob of angry male prisoners gathered around, jeering and taunting as Bennett-Hillier jostled her way through the 100-strong crowd.

The bloke was beaten and bloodied.

Two giant egg-shaped mounds protruded from his head, the aftermath of having his skull repeatedly rammed into a brick wall.

A few minutes more and the inmates probably could have finished him off.

But prison officer, Trixie, couldn’t let that happen – as much as she might have liked to.

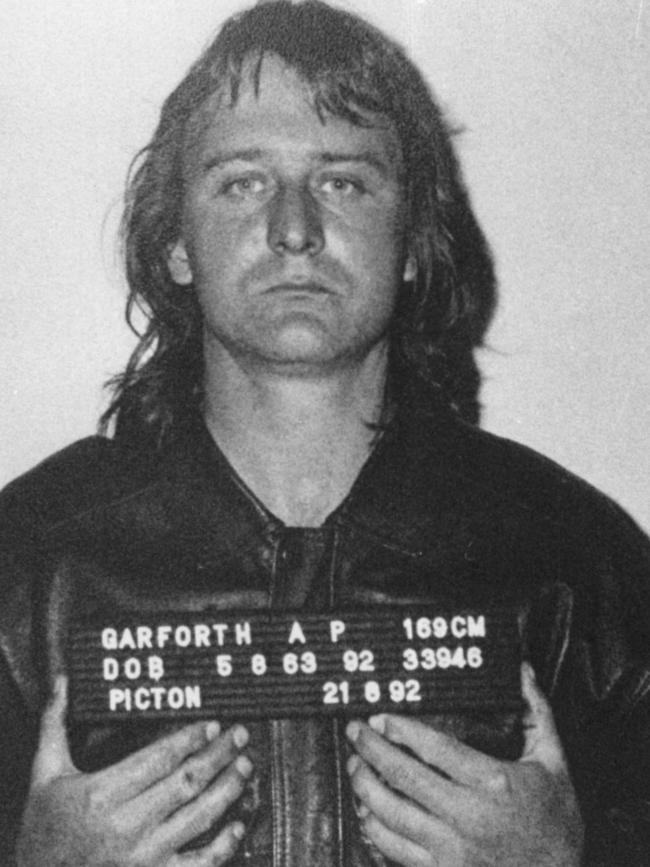

The man was Andrew Garforth, killer of nine-year-old, Ebony Simpson – and his fellow inmates knew exactly what he’d done.

Details of Garforth’s shocking crime had been splashed across the news for months – they’d heard how he’d picked up little Ebony on way her home from school in Bargo in Sydney’s south west in 1992.

How he’d driven her to a nearby dam, bound her hands and feet with wire, and thrown her tiny frame in the water, her pink backpack loaded with rocks.

They’d also heard how a depraved Garforth joined the group of locals searching for Ebony, in the days after her then mysterious disappearance.

Now, they wanted blood.

The scene was so volatile that Bennett-Hillier’s colleague, a fellow prison officer, refused to step in ‘The Circle’ (‘The Circle’ is the central circular area at Goulburn prison, also colloquially known as “the human zoo”.)

“I knew what Garforth was in for and I also disliked him but I still couldn’t let them continue attacking him. It was my duty of care to stop it,” Bennett-Hillier, 68, told On Guard.

“The other officer, she wouldn’t come in so I just said, ‘lock the gate’ and she left me in the yard by myself with 100 inmates.

“I wasn’t scared because they’d done what they want to do, they weren’t going to attack me. Plus, they knew me, that I was fair and treated them with decency.”

The inmates stepped aside to let Bennett-Hillier through.

“Oh, you naughty boys!” she scolded, before bending down to where Garforth was lying.

“He had big lumps on his head and he was bleeding. I picked him up and said, ‘you come with me’.”

While Bennett-Hillier was escorting Garforth to safety, the inmates shifted their attention to a frail older man sitting on a bench near the gate.

“He’s next,” jeered one of the prisoners.

“No he’s not!” shouted Bennett-Hillier.

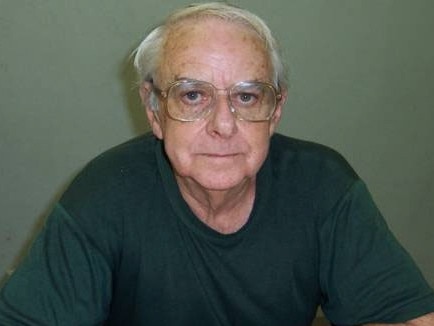

The man was Australia’s most notorious paedophile, Robert ‘Dolly’ Dunn.

A former Marist Brothers teacher, Dunn was wanted for 90 child sex offences when he went on the run through Central America, before being tracked down by television program, 60 Minutes, in 1997.

A self-confessed “boy-lover” Dunn abused boys as young as seven, often filming his sexual encounters so he could review them.

“(He was a) creepy lookin’ damn thing,” recalls Bennett-Hillier, a grandmother-of-six.

“He was scared shitless. He was sitting on the seat, petrified. Shaking in his boots.”

Bennett-Hillier called for back-up to take Garforth to the prison hospital, while she locked Dunn in his cell where he couldn’t be harmed.

Both men would later separately thank Bennett-Hillier for saving their lives.

“This Garforth, he said to me, ‘Oh, thank you, Miss. You’ve saved me life’,” Bennett-Hillier said.

“Don’t thank me,” she said. “I’m just doing my job.”

Then a mother-of-three, the irony of saving a paedophile’s life wasn’t lost on her.

“I had to deal with a lot of paedophiles. You just had to put up a barrier. You weren’t in there to judge them. They’ve already been judged. You just had to do what you do.”

Catch up on more episodes of On Guard below: