NT teen’s death: Shots fired by cop from Canberra under scrutiny

On November 9, 2019, 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker was shot dead by police in the Northern Territory. Constable Zachary Rolfe, who is from Canberra, has been charged with murder. At a committal hearing this week, it was revealed the 2.6 second window between shot one and shots two and three is crucial.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

On November 9, 2019, in the remote community of Yuendumu in the Northern Territory, 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker was shot dead by police.

He was wanted for breaching his parole and when two police officers attempted to arrest him, he stabbed one — Constable Zachary Rolfe — with a pair of scissors.

Constable Rolfe responded with lethal force. He fired one shot, then another two shots, as Walker wrestled on the ground with Constable Rolfe’s colleague.

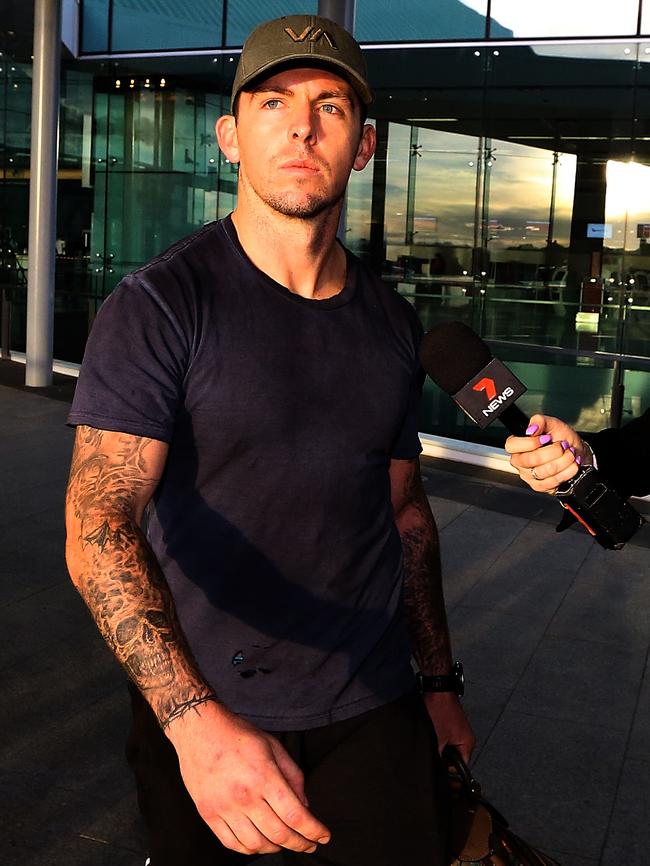

Four days later, 29-year-old Constable Rolfe was charged with murder.

He is now suspended and currently on bail, living in the ACT with his family. He intends to plead not guilty.

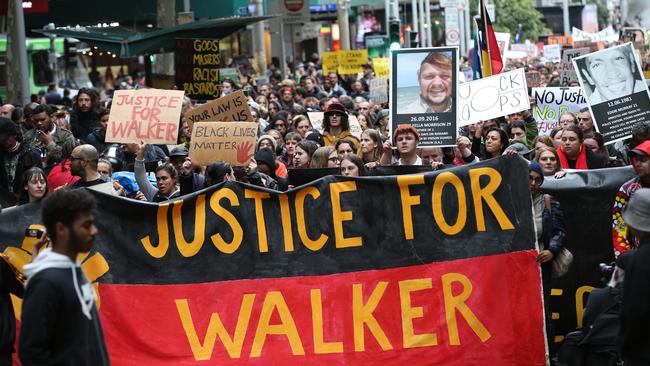

The fatal shooting of the Indigenous teen sparked a national uproar.

People across the country took to the streets in protest against police brutality just as the Black Lives Matter movement was on the cusp of exploding.

This week a committal hearing in Alice Springs delved into the circumstances of the shooting and the question of reasonable force.

The 2.6 second window between shot one and shots two and three is crucial.

Experts have testified that the final two shots were excessive and unnecessary as the threat Walker posed had been minimised by the first shot.

This is how the case unfolded.

The setting sun cast an orange glow over the Central Australian desert and the red dirt crunched under Constable Zachary Rolfe’s boots.

It was about 7.15pm on November 9, 2019, and Rolfe was in the remote community of Yuendumu, about 300km north of Alice Springs.

He and three other Northern Territory Police Force officers were looking for 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker.

They’d been called in to town as reinforcements after Walker had run at two local police officers with a tomahawk three days earlier during a failed arrest attempt.

The officers, including one with a long-arm rifle in his hands, were outsiders and treated with suspicion.

Constable Rolfe, an ambitious and decorated young officer with a background in the defence force, was treading carefully.

“Hey, little one,” he remarked to a wide-eyed child as he moved towards house 511.

The police asked locals if they’d seen Walker around, most shrugged and shook their heads. But a man across the oval hinted that Walker might be inside house 511.

Constable Rolfe and Constable Adam Eberl agreed to have a look.

“Hey missus, where is Arnold at?” Constable Rolfe asked a woman outside the home.

“Can we go check inside?”

The officers stepped into the dark home and light beamed from their torch.

TWO LIVES COLLIDE

In a matter of minutes, the parallel lives of these Constable Rolfe and Walker collided in catastrophic circumstances.

Walker was shot three times after stabbing Rolfe with a pair of scissors during the tragic arrest attempt.

Walker died on the floor of a police station and four days later, Constable Rolfe was charged with the murder.

The shooting ignited strained and tense relationships between police and Indigenous communities and sparked protests and uproar around the country.

Through access to crucial evidence tendered during the committal hearing this week, The Saturday Telegraph can reveal how the most politically-charged case of the decade unfolded.

It is a story of black and white Australia. The story of a decorated policeman and humble high achiever from a charmed background in the nation’s capital and a young Indigenous man from a remote community who was in and out of detention from the age of 14 and let down by a seemingly unfixable system.

A TROUBLED HISTORY

Seated inside court in October, 2018, a sombre picture was painted of Walker’s circumstances.

His “very bad” criminal record stretched back to when he was 14 years old. A psychological assessment determined he had cognitive issues that hampered his ability to control his impulses.

“That is going to be with him for the rest of his life in all likelihood,” his solicitor told the court.

Walker had a history of ignoring court orders and gave up on residential drug and alcohol programs when things got “too distressing” or tough.

He was learning new ways to cope with that and shed the habit of running away and thinking later.

Yuendumu — home to his mother, who was supporting Walker in court — and nearby Papunya no longer welcomed him, the court heard. His offending had become too much for the remote communities to bear.

He broke into and damaged the Yuendumu Community School in the middle of the night.

A girl close to Walker, whose grandparents had welcomed Walker into their home in Yuendumu, had been the victim of multiple assaults.

According to court documents, he dragged her away from her cousin and sister at a football oval and punched and kicked her. He threw a rock at her back and bit her cheek in a fit of jealousy.

Walker, who faced issues with petrol sniffing and marijuana in the past, pleaded guilty to the offending but wanted to change.

“He is certainly aware that in two weeks time he turns 18,” Walker’s solicitor said, according to audio recordings made available by Northern Territory Courts.

If he ruins the opportunity to go to DASA (Drug and Alcohol Services Limited), the lawyer added, he knew the adult prison system would be his fate.

“As an adult he will be treated a lot less leniently than he has been to date.”

For assaulting police, breaking and entering and escaping detention, Judge David Bamber sentenced Walker to nine months’ detention.

But the time in custody was suspended to allow Walker to receive drug and alcohol treatment.

“Go to DASA, hopefully learn to control yourself and someone will work out where you best stay after you get out of there,” Judge Bamber said.

“That is the big thing that needs to be worked out. Where are you going to be best able to live and hopefully do some meaningful activities and stay out of trouble. Otherwise I’m concerned for the future.”

In 20 minutes, Walker’s court hearing had touched on a smorgasbord of disadvantages that disproportionately affect Indigenous communities.

His family did not respond to requests for interviews as part of this story and only hints of his background can be gleaned from his criminal history.

After his death, his former lawyer, Sophie Trevitt, described him as an earnest, shy, kind young man who was a victim of the system.

“I want you to understand that it wasn’t bad luck that saw Kumanjayi Walker shot and killed by police,” she wrote in The Guardian last year.

“It was the devastating, completely unsurprising, unforgivable natural conclusion of a system that has seen 424 First Nations People die in custody since the end of the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody.”

At one point in Walker’s criminal history, the judicial system seemed at a loss as to what to do with him.

In 2017, Judge Bamber, while sentencing Walker for an unlawful entry offence, said he didn’t have an adult taking any responsibility for him.

One of Walker’s relatives, who was in court supporting the teenager at the time, wanted to take him to the bush mob to connect with his culture.

“These are matters where the sentencing options are virtually nil because of the fact the defendant is a repeat offender,” Judge Bamber said in his judgment.

Walker was jailed for three months for breaking into the Yuendumu Outback Store.

Last year, he was sentenced as an adult.

He received a 16-month suspended sentence for aggravated assault and assaulting police, was released from custody and ordered to wear an electronic monitoring device while he resided at the Central Australian Alcohol Program Unit in Alice Springs.

He had 10 days left at the unit when, on October 19, he cut off the electronic monitoring device around his ankle.

Six days later, a warrant was issued for his arrest.

AN ACT OF BRAVERY

Hanging on a wall inside the British High Commissioner’s residence in Canberra, is a striking piece of Indigenous artwork painted in pink and orange hues.

The artwork, painted by Barbara Weir and given by businessman Richard Rolfe during a Century Of Armistice event last year, signified two heroic river rescues in Australian history. One of those rescues on the swollen Hugh River in the Northern Territory involved Rolfe’s youngest son, Zachary Rolfe.

In 2016, Rolfe, a former Defence Force member, was a week into his new job as probationary constable with the Northern Territory Police Force when he came across two tourists swept downstream by raging flood waters.

He’d stripped down to his underwear and trekked five kilometres downstream until he came across a woman clinging to an island surrounded by water.

Rolfe and his colleague, Senior Constable Kristen Jamieson, received the Clarke Gold Medal for Bravery from the Royal Humane Society in 2018.

Former detective Allan Sparkes, who earned a Cross of Valour award for his own harrowing rescue of a young boy from a storm water drain when he was in NSW Police, personally nominated the officers for the bravery medals. He did so after it became clear the Northern Territory Police weren’t going to recognise their heroism.

“Considering the level of bravery shown by the three people, I thought that was so wrong morally and professionally, it was just wrong,” Sparkes said.

“(Zac) has shown to be a person who is willing to sacrifice himself to help others.”

Sparkes was a close friend of the Rolfe family, having met Richard and his wife Deb, a lawyer, at a dignitaries event in Canberra two years earlier. The Rolfes, both AM recipients, are well known philanthropists in Canberra with support for veterans, the homeless, the Heart Foundation and Indigenous youth programs.

Governor-General Peter Cosgrove once said there wouldn’t be worthy activity in Canberra they weren’t involved in.

“As a duo, you’re unbeatable,” he told Richard Rolfe at a 2017 awards ceremony.

NOVEMBER 6, 2019

At 6.25pm on Wednesday, November 6, Constables Chris Hand and Lanyon Smith visited house 577 in Yuendumu.

It was the home of Eddie and Lottie Robertson, respected Warlpiri elders who had taken a young Walker under their wing as their adopted grandson.

According to witness statements tendered in court, Robertson allowed the officers to go into the home and indicated that Walker, who had been added to the NT Police’s arrest targets list days earlier, was in the bedroom.

The body-worn video, tendered in court last week above, showed the constables cautiously approaching the bedroom door and knock.

Walker’s girlfriend emerged and stood in the doorway.

Police officers who later viewed the footage believed the girlfriend stalled their entry into the room to give Walker time to grab a tomahawk off the floor.

In a split second, the video captured Walker lunging at the officers with the weapon in his hand.

The court heard this week that in the Northern Territory, police are taught the concept “knife equals gun” — meaning an officer is justified in drawing his or her firearm if someone pulls a knife on them.

But Constable Hand “froze”.

“You know your training, they train you in defensive tactics…,” he told investigators on November 14.

“Oh, it’s an egged weapon you use a firearm, you draw a firearm … you can you know, taser, spray or firearm.

“But until that actually happens you don’t even think of anything like that. It’s, you know, a bit of self-preservation.”

With lightning speed, Walker manoeuvred around the officers before he sprinted into the desert.

In a later interview and on reflection, Constable Hand said Walker would have had ample opportunity to strike them but didn’t.

He didn’t think “of using a firearm because of my previous experience in remote communities, especially Yuendumu”.

Walker’s grandmother was grateful for that, Hand added.

Reeling from the close call, the officers pleaded with Robertson to “go and get” Walker to avoid any further violence during the next arrest attempt.

That night, Sergeant Julie Frost, the most senior officer stationed at Yuendumu, viewed the footage. It hit a nerve, not only because it involved her colleagues but Constable Hand was her partner.

Sgt Frost went around to the house to speak with the Robertsons.

“I told them, ‘Arnold could’ve been killed as well, or could’ve been shot because of his actions’,” Sgt Frost told them, according to her statement.

They came to an agreement — Walker could attend the funeral of a relative on Saturday as long as he handed himself into the police station afterwards.

If he didn’t turn up, Sgt Frost warned, “we’re getting members from Alice Springs and they will go in a lot harder than what we do”.

She called her boss, a superintendent based in Alice Springs, on Thursday night and requested more police resources in Yuendumu.

NOVEMBER 9

On the morning of Saturday November 9, nursing staff from the Yuendumu Health Clinic turned up to the police station.

They had been ordered to evacuate.

Someone had tried to break into the nurses’ accommodation overnight and staff were fed up.

The clinic car had a window smashed and first aid equipment thrown around the place.

Their managers directed them to evacuate the clinic.

One nurse, who had 39 years in the profession, including five years working in remote communities, said she’d never been evacuated from a community before.

“At Canteen Creek, when they had riots out there, we did not evacuate,” she told police in an interview on February 12, 2020.

“This was tangible, we could feel it. We didn’t walk in Yuendumu, you don’t walk around, you don’t go to the shop, you don’t do anything that puts you at risk of your personal safety.

“I will never ever go back to Yuendumu.”

She described how her colleagues woke up in the middle of the night and heard someone trying to get into their home.

“They were waking up and had all the lights on, and they could hear everything going down,” the nurse said.

“These people were not afraid to break in.”

Rolfe’s defence barrister told Alice Springs Local Court during a preliminary hearing this year that Walker was among those suspected of orchestrating the break-in.

If true, Walker could not have known at the time that he would end up needing urgent medical intervention 24 hours later.

The nearest health clinic was 50 minutes drive away in Yuelamu and the nurses there wanted police escorts if they were called in to Yuendumu.

But Sgt Frost, who had requested more police from Alice Springs to deal with the influx of people in the community for the funeral, didn’t have the resources for that.

The evacuation of the Yuendumu Health Clinic added to the perfect storm forming on November 9.

According to statements from local police, there had been instances of rioting and recent conflict between remote communities.

The funeral would bring members of these communities together.

As Sgt Frost described the situation: “ … it was just sitting in the background brewing and we knew it was about to explode”.

Members of the Immediate Response Team (IRT) based in Alice Springs were tasked to travel to Yuendumu on Saturday afternoon. Their deployment was to bolster the police presence in the community that night and to find and arrest Walker.

Before the IRT left Alice Springs, they watched the body-worn video of the tomahawk incident days earlier.

Constable Breanna Bonney said the footage left her feeling physically ill.

A day prior, on Friday, Bonney and other officers, including Constable Rolfe, went to Warlpiri camp in Alice Springs. They’d received information Walker may have been there but they didn’t find him.

“The idea behind us watching this footage was to give us an accurate understanding of the high risk behaviour exhibited by Mr Walker towards police attempting to arrest him,” Bonney told police in her statement.

“By watching this footage I recall feeling physically nauseous from the fear that it caused me for the lives of my colleagues who were trying to arrest him.”

According to the statements of other police, there was a general feeling Hand and Smith should have handled the tomahawk incident differently.

“My thoughts were around operational safety — what were the members thinking?” IRT member Constable Adam Eberl said in his statement.

“ … yeah, I was surprised to be honest that either a Taser or a firearm wasn’t used on him …(a) Taser wouldn’t have been the option, a firearm would have been if I was in that position.”

When the IRT arrived at Yuendumu Police Station that night, Frost briefed them. She later claimed she had a challenging conversation with the IRT and felt they were trying to take over the operation.

A colleague recalled Frost telling her local officers “can you stay behind, let them arrest him”.

“Seeing the sort of violence (Walker) displayed towards members of the police, one of us (will) probably get hurt,” according to that officer’s witness statement.

The plan was formed to arrest Walker at 5.30am the following day.

But the IRT would gather intelligence about where Walker might be during the night and if they stumbled across him, they’d arrest him.

HARROWING FOOTAGE

It was about 7pm when Constable Rolfe and three IRT members approached house 511 in Yuendumu.

The 29-year-old, who’d had an accelerated career through the NT Police Force since joining in 2016, switched on the body-worn camera attached to his vest as he got out of the car.

The footage captured is more than an hour long and one of the most harrowing pieces of evidence in the case.

An edited version was played at Constable Rolfe’s committal hearing.

The video showed Constable Eberl and Constable Rolfe walk into the front door while Constable Anthony Hawkins and police dog handler Constable Adam Donaldson stayed outside.

People began to gather around the house, intrigued by the police presence, and Hawkins wondered whether it served as a warning to Walker that police were closing in.

For the full rundown of the events that unfolded over the next 90 minutes see separate story on facing page.

THE AFTERMATH

Inside the emergency department at Alice Springs Hospital at 1.30am, a nurse examined the wound on Constable Rolfe’s shoulder.

The stab wound was 3mm x 3mm. There was a four centimetre abrasion on his right bicep and the officer also said he’d been hit in the head during the arrest.

Constable Bonney called Rolfe to check in on him about half-an-hour later.

“Rolfe was becoming emotional,” Bonney later told investigators of the phone conversation.

“He was speaking quietly and slowly and his voice was trembling.”

Over the following days, Rolfe recovered at home in Alice Springs.

Fellow officers dropped by for a barbecue or to check in as interest in the Yuendumu shooting intensified not only in the Northern Territory but around Australia.

Protests against police brutality and Aboriginal deaths in custody popped up in capital cities around the country. Red handprints were left on police stations around the NT.

Conflicting versions about exactly what happened before Rolfe pulled the trigger only added to the pressure on the police force and the NT Government to provide answers.

Unrest was simmering.

Two days after the shooting, November 11, Jamie Chalker stepped into the role of NT Police Commissioner.

Sources close to the investigation believe the decision to charge Constable Rolfe with murder was made by police and then the DPP late on Monday or early Tuesday.

But the development was kept under wraps for 48 hours while Mr Chalker and Chief Minister Michael Gunner travelled to Yuendumu.

In a strongly-worded speech, Gunner promised the reeling community that “consequences will flow” as a result of the investigation.

Back in Alice Springs, the threats against Constable Rolfe were escalating as his identity filtered into the public domain and he moved to Darwin for his own safety.

His mother arrived and stayed with her son at a secure apartment block.

On Wednesday November 13, Rolfe returned from a run and found a handful of detectives waiting to arrest him and charge him with murder.

One arresting officer, Detective Isobel Cummins, said in her statement that she and other investigators raised concerns about the “rushed” charging process.

“On numerous occasions, I and other investigators had voiced our concerns regarding the rush process regarding this decision,” she said.

“And the fact we were not comfortable with the current situation without a full assessment of the evidence and ability to investigate objectively.”

Rolfe was eventually granted bail by a magistrate and returned home to Canberra. He intends to plead not guilty to murder.

Meanwhile, many Walker’s relatives and Yuendumu community members spent last week in a peaceful sit-down outside the Alice Springs Courthouse as details of the shooting were aired for the first time.

“We want justice because it’s hurting us, it has hurt us and tormented us, that’s what it does,” relative Ned Jampijinpa Hargraves said.

The committal hearing returns to court on September 25 when Rolfe’s lawyers will argue he has no case to answer.