SOUTH Australia is sometimes referred to as the crime capital of the nation.

And there’s no doubt many infamous crimes have occurred here — the Snowtown and Truro murders, the disappearance of the Beaumont children, the Somerton Man and the more recent deaths of the Rowe family, Carly Ryan, Anne Redman and Pirjo Kemppainen.

But there are thousands of other bizarre crimes across our state that haven’t received as much press coverage — especially those from our state’s earlier days.

To mark the SA History Festival, here are some crimes dating back to the early 1900s that you’ve probably never heard of.

And don’t miss Part One of this special — bizarre SA crimes of the 1800s.

The Madam of Mount Gambier — late 1800s

Catherine “Kitty” Temple must have created quite a stir when she arrived in Mount Gambier in the 1860s.

Loud, outspoken and with a fondness for hard liquor, Kitty ran a hotel in the town with her husband, William.

Throughout the late 1800s, the pair was frequently in trouble with the law for running a “sly grog shop” — selling alcohol with no liquor licence.

Though Kitty managed to keep her name out of the papers — it was always her husband who was hauled in front of the courts to face the charges — she was also well known for other misdemeanours.

Kitty was known as a Madam of Mount Gambier, keeping the male patrons of her hotel happy in more ways than one.

The rumours continued even after the couple moved their hotel to Caveton, a small township laid out in 1866 about 15km south of Mount Gambier.

As an article in the Border Watch, published in January 1952, put it: “‘Kitty’ Temple established her ‘hotel’ there (in Caveton). Many hair-raising tales are told of the ‘beverages’ ‘dispensed’ to ‘thirsty travellers’ by ‘Kitty’.”

Court documents also allude to her reputation.

In September 1882, labourer John Flynn was charged with attempting to commit rape on Kitty.

Flynn had visited their house the night before and was known to the couple.

The defence asked her: “Did you say to him, ‘If you come (back) tomorrow my husband will be at Mount Gambier, and we shall have the house to ourselves. I will get some more whisky’?”

Kitty denied saying this, though the defence lawyer later labelled the incident “a drunken spree” and said he understood “the plaintiff was as bad as the prisoner”.

Despite this, Flynn was found guilty of indecent assault and sentenced to 12 months’ jail with hard labour.

Kitty’s morality was further questioned after her husband’s death in 1897, when she chose to live with her boyfriend, Bruno.

She died in 1907, and the infamous Temple Inn was sold off for the grand sum of 13 pounds.

A private residence was later built on the site, but Kitty’s legend lives on — someone has hidden a geocache (a reward for GPS treasure hunters) on the spot labelled ‘Pussy Town’.

Adelaide Arcade, a ghost and a hanging — 1904

A bootmaker and amateur juggler, Thomas Horton shot dead his wife, Florence Horton, on Rundle St — now Rundle Mall — outside Adelaide Arcade on February 27, 1904.

Horton fired three bullets at his 21-year-old wife in a jealous rage — he was allegedly unhappy about his wife’s supposed relationship with the father of her illegitimate child.

Reports at the time suggested Horton told his wife he had a present for her, to which she supposedly replied “a present of bullets” before she was shot in the back.

Florence, who was with friends, was carried to a tobacconist’s shop in the arcade, where she “breathed her last”.

Horton was sentenced to death and executed on May 13, 1904, and buried in the Adelaide Gaol grounds.

Florence’s ghost is one of three said to still haunt Adelaide Arcade.

Girl Guides and gambling — 1923

When you think of the Girl Guides, you don’t exactly associate them with criminal conspiracies investigated at the highest levels of government.

But back in 1923, the organisation became embroiled in a complicated case involving (shock, horror) gambling.

In May that year, as part of the Girl Guides Fete, electricians called Dankel and Company set up a fundraising “guessing competition”.

The public was invited to guess how far the wheel of a bicycle, supplied by Bullock Cycle Stores, would travel in a week.

Tickets could be purchased for sixpence, and the closest guess would win the bicycle itself.

The competition, including the donation of the bicycle, had been organised by members of the Girl Guides Association, including a Mrs Bernstein and the Lady Mayoress, Mrs Cohen.

But the whole event quickly came to the attention of Plainclothes Constable C. Stewart, who raised his concerns to the Police Commissioner, Raymond Leane.

Mr Leane then forwarded the matter to the Chief Secretary, Attorney-General and Crown Solicitor, stating that a breach of the Lottery and Gaming Acts 1917 to 1921 had occurred because “skill could not possibly govern a correct guess as to the distance travelled”.

He was not sympathetic to the fact the competition was a fundraiser for the Girl Guides, stating that “when funds are required for purposes of this nature and charity, that gambling should not be indulged in, particularly when it encourages young girls to break the law”.

Electrical company owner Mr Dankel said that he had been unsure about the legality of the game when it was suggested, but was told by women from the Girl Guides that any responsibility related to the game would be borne by the association.

Mrs Bernstein was interviewed and confirmed that all proceeds from ticket sales would go only to the Girl Guides.

The powers that be decided a prosecution was not possible because of a lack of uncorroborated and additional evidence.

Instead, Mr Dankel and Mrs Bernstein were cautioned — and the fundraising attempt scrapped.

Murder on Grenfell St — 1929

Constable John Holman was off duty and just a week away from getting married when he was shot and killed in Grenfell St on February 23, 1929.

The 23-year-old police officer had finished his shift and was about to leave the City Watch House when he was sent with Constables Ernest Budgen and Clement John King to a house near the Crown and Anchor Hotel in Grenfell St, where a number of men were said to be creating a disturbance.

When they got there, all was quiet, though a motorcycle and side car sat strangely in the middle of the road.

The men in the house denied any knowledge of the motorcycle, so the officers decided to take it back to the City Watch House.

Just as Constable Holman started the engine, two men appeared from a nearby laneway and called on the officers to stop.

Don’t shoot. I’m a police constable!”

As one of the men, John Stanley McGrath, pulled out a revolver, Constable Holman started to yell: “Don’t shoot. I’m a police constable!”.

But it was too late — McGrath fired some shots, one which hit Constable Holman in the stomach, before running off.

The officer tried to follow the assailants, but collapsed after running a few metres.

He died an hour and a half later.

McGrath was charged with murder, while the second suspect, Albert Matthews, was charged with murder and attempted murder — though he was later acquitted of both charges.

During the trial, the jury felt sorry for McGrath and — while convicting him of murder — asked the judge to spare his life.

Justice Mellis Napier agreed, sentencing McGrath to life with hard labour, arguing that the prisoner probably shot the constable without realising he was a police officer.

Constables Budgen and King were awarded the King’s Medal on May 12, 1930, for conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty.

Constable Holman’s mum, Eliza, was later awarded 250 pounds in compensation from the courts because she no longer received 2-3 pounds a week from her son’s pay, which helped with the family’s housekeeping expenses.

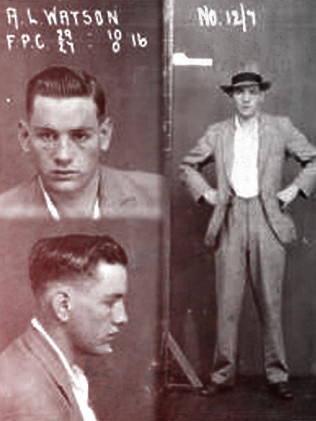

A serial offender and a dog-stealing incident — 1931

In the 1930s, Allen Leon Watson was a name well known by local police.

The labourer spent several stints in Adelaide Gaol during that era for a range of offences including assaulting police, resisting police, drunkenness, indecent behaviour and indecent language.

But the most peculiar charge Watson faced was that of “dog stealing”.

In February 1931, along with William Henry Duell, Watson was accused of stealing an Alsatian dog, valued at 100 pounds, from explorer Francis Birtles.

The prosecution said Mr Birtles had tied his dog to a motor car in the yard of the Victoria Hotel, in Adelaide’s CBD, about 2pm, leaving some water in a dish so the pooch didn’t get too thirsty.

But when he returned about 4.30pm, the dog was gone.

Duell admitted untying the dog, but said that it then followed him and Watson into a car.

They then took the dog for a drink and meal, as they claimed it was famished for water.

Watson said he then planned to return the dog to the hotel.

Mr B.J. Kearney, who represented the defence, told the court that the dog was “of a very loveable disposition and appears ready to make friends with anyone”, before asking if the dog could be brought into court.

When it entered, The Register News reported that it “fawned upon several persons”.

But this was not enough to convince the judge of Watson and Duell’s innocence. (It probably also didn’t help that a witness said they saw the duo enticing the dog into their car).

Both men were fined five pounds for dog stealing.

Watson remained in South Australia — and frequently in front of the courts — until the mid-1940s, when he moved to Western Australia and continued his life of crime.

Bizarre Butterfly Heist — 1947

There have been many strange thefts over the years, but perhaps none as bizarre as the South Australian Museum’s great butterfly heist.

In 1947, the museum discovered more than 600 of its butterfly specimens — many irreplaceable — had been stolen.

The thefts only came to light after the Melbourne Museum reported a similar incident.

The investigation pointed to Colin William Wyatt, a former British skiing champion who had moved to Australia in 1939 with his wife, joined the RAAF during World War II and had since returned to the UK.

Scotland Yard picked up the case. They searched Wyatt’s house, finding most of the specimens in four crates labelled “scientific specimens” that Wyatt had picked up from the docks on January 24, 1947.

He was charged over the theft of more than 1600 butterfly specimens from museums across Australia.

During a court case in London on May 21, the prosecution said Wyatt took up his hobby of butterfly collecting in 1944 to distract himself from marriage troubles.

“He thought that his wife was doing what she ought not to have done, and that the war had broken up his marriage,” defence lawyer Gerald Howard told the court.

“He therefore plunged back into the collecting of butterflies with redoubled fervour. He

went to several Australian museums and stole them.”

Wyatt admitted he used to take the specimens from drawers and put them into tins which would hold up to 100 butterflies, then walk out of the museums with the tins in his pockets.

The prosecution argued that the specimens were almost priceless. The defence countered that it was never Wyatt’s intention to sell them.

In the end, Wyatt was fined 100 pounds over the thefts, and forced to return the butterflies to Australia.

The 1948 Australian Museum annual report states that the butterflies were returned on August 11, 1947.

Experts from Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide met at the South Australian Museum to sort through the specimens “as well as possible”, given many of the labels had been changed or destroyed in transit.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of State Records SA with the preparation of this article.

The lie that cost underworld figure his life

When Carl Williams lied about Michael Marshall’s involvement in a contract killing, he as good as signed the hotdog salesman’s death warrant.

Lunchtime jewel heist which rocked Sydney’s CBD

In what was considered the biggest jewellery heist of the first half of the 20th century, in 1947 a thief managed to steal jewels worth about $600k today. But his glory was short-lived.