How corrupt cop Roger Rogerson led to birth of Undercover Branch

This is the untold story on one of the most secretive units within the Police Force. And its origins trace back to the shooting of an honest cop by corrupt detective Roger Rogerson. EXCLUSIVE AUDIO

It was one of the worst police corruption scandals in NSW Police Force history: an honest cop shot in his kitchen for refusing to take a bribe.

But few could have known this incident — suspected to have been masterminded by the deeply-corrupt detective Roger Rogerson — would lead to the birth of the NSW Undercover Branch, and the formalisation of their tactics around Australia.

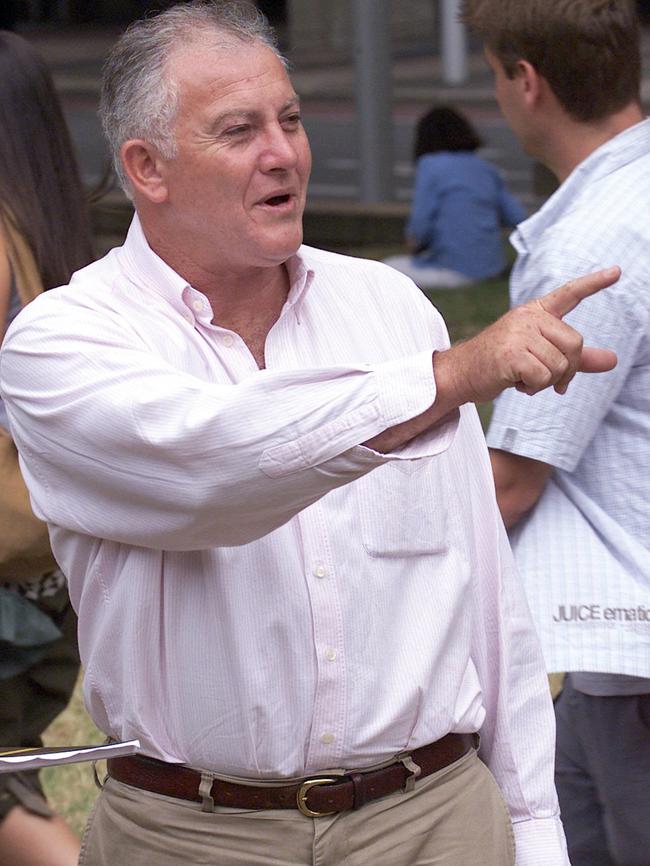

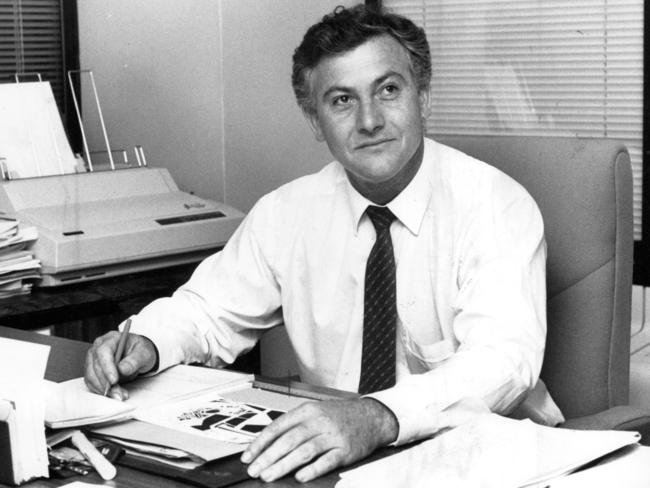

For Michael Drury, the victim that night, it’s a tragic tale with a silver lining, one that would end up positioning him a central figure in the future of Australian undercover work.

On June 6, 1984, the Drug Squad officer was in his kitchen washing dishes when a gunman appeared through the window and shot him twice in front of his family.

Few people expected him to live. Twelve days later he woke up and gave a dying deposition to detectives, naming Rogerson as the brains behind the attempted assassination.

Rogerson, he explained, had wanted him to change his court-evidence against a heroin dealer, Alan Williams, and Drury’s refusal to do so, and accept an accompanying bribe, was the motivation behind the shooting. (Rogerson was acquitted of the shooting in 1989, but is currently serving a life sentence for the 2014 murder of a drug dealer, Jamie Gao.)

Realising the threat to his safety, the Police Commissioner, Jack Avery, arranged a job for Drury at the Australian Consulate in Los Angeles to get him out of the country.

“My life was in danger and a decision was made to send me overseas until they got on top of it,” Drury said.

MORE IN THIS SERIES

‘HITMAN’ HIRED BY MODEL: ‘SHE WAS COLD AND RUTHLESS’

CONFESSIONS OF A KILLER: ‘I DID IT, I DID IT, I DID IT’

‘I SPENT SEVEN MONTHS INFILTRATING PAEDOPHILE RING’

He’d been in his new role barely three months when, one day, his desk phone rang; it was his old boss at the Drug Squad, Jim Willis.

Willis had become concerned about the quality of his unit’s undercover operations, saying they had no oversight, no accountability, and little duty of care for the staff.

At the time, undercover work was piecemeal; many units did the work, but there was no formal training, no dedicated branch, no welfare checks or debriefing sessions.

“We taught ourselves on the streets, it was madness,” said Drury, who returned to Australia in 1988 armed with the latest techniques from the world’s best: the FBI, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the LAPD, and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. He went on to adapt these techniques around Australia’s legal framework and wrote the first formal pilot program for undercover operatives in Australia, teaching the course to police forces around the country, along with the AFP, the Royal Hong Kong Police Force and ASIO.

“The excitement of it was that you didn’t have to chase them for the evidence. They brought it to you,” he said.

Undercover policing grew out of a difficult era in this state’s policing history, a time of endemic corruption, external reviews, and a royal commission set up in the early ‘90s to try expose its root causes. Operations were slapdash at times, leaving operatives exposed to extreme risks and life-threatening moments. In Kings Cross, a female operative survived a drug-rip when a .357 pistol pressed into her skull miraculously malfunctioned. In a separate case, an operative working on the NSW/ACT border was kidnapped by drug dealers, gaffer-taped and held for ransom until colleagues eventually got him back alive. “That’s all it takes,” said Drury. “One question, one remark, one wrong move.”

Disasters of this kind are far less likely to occur today, but some aspects of drug-buying cannot be removed from the risk equation, particularly the leap of faith required between the dealer and buyer, the target and police; neither will ever know if they’re being set up for a robbery, an arrest, or something more sinister. “They’re not scared of being arrested,” said Andy MacFarlane, a former operative who spent nine years working undercover. “They’re scared of you coming to rip off their drugs.” But for operatives, the reverse applies too. “They (the dealers) know we’re turning up with $500,000,” he said. “You can’t get that out of an armed robbery anymore.”